By C.H. Rohith

The clocks of justice in India tick much slower than any citizen would hope. At the time of writing this article, 5.22 crore cases are pending across all levels of courts in India. Quasi-judicial bodies like the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) and the Central Administrative Tribunal (CAT) also have large backlogs.

While there are multiple causes for judicial delays and pendency, from procedural issues to infrastructure constraints, one important aspect of the judiciary that receives insufficient scrutiny from the public is the judicial budgets. Most states spend less than 1% of their annual budget on the judiciary, whereas the Union government allocated just 0.07% in 2025-26. Overall, India spends only 0.14% of its GDP on the judiciary. For comparison, most European countries allocate 0.31% of their GDP to their judiciary.

Several studies have highlighted the positive relation between adequate public funding and judicial independence, which in turn drives economic growth. Given these broader implications, the budgetary allocation to the judiciary and judicial budgeting process in India warrant urgent attention from the public and policymakers.

Stark Disparities in Budgetary Allocation to the Judiciary

Findings from our recent study titled 'Strengthening the Rule of Law: Role of the Finance Commission' revealed vast inequalities in budgetary allocation to the judiciary. According to the 2024-25 budget estimates, the Union government allocated merely 6.36% of the all-India judicial budget, with the states accounting for the remaining 93.64% of the budgeted expenditure on the judiciary.

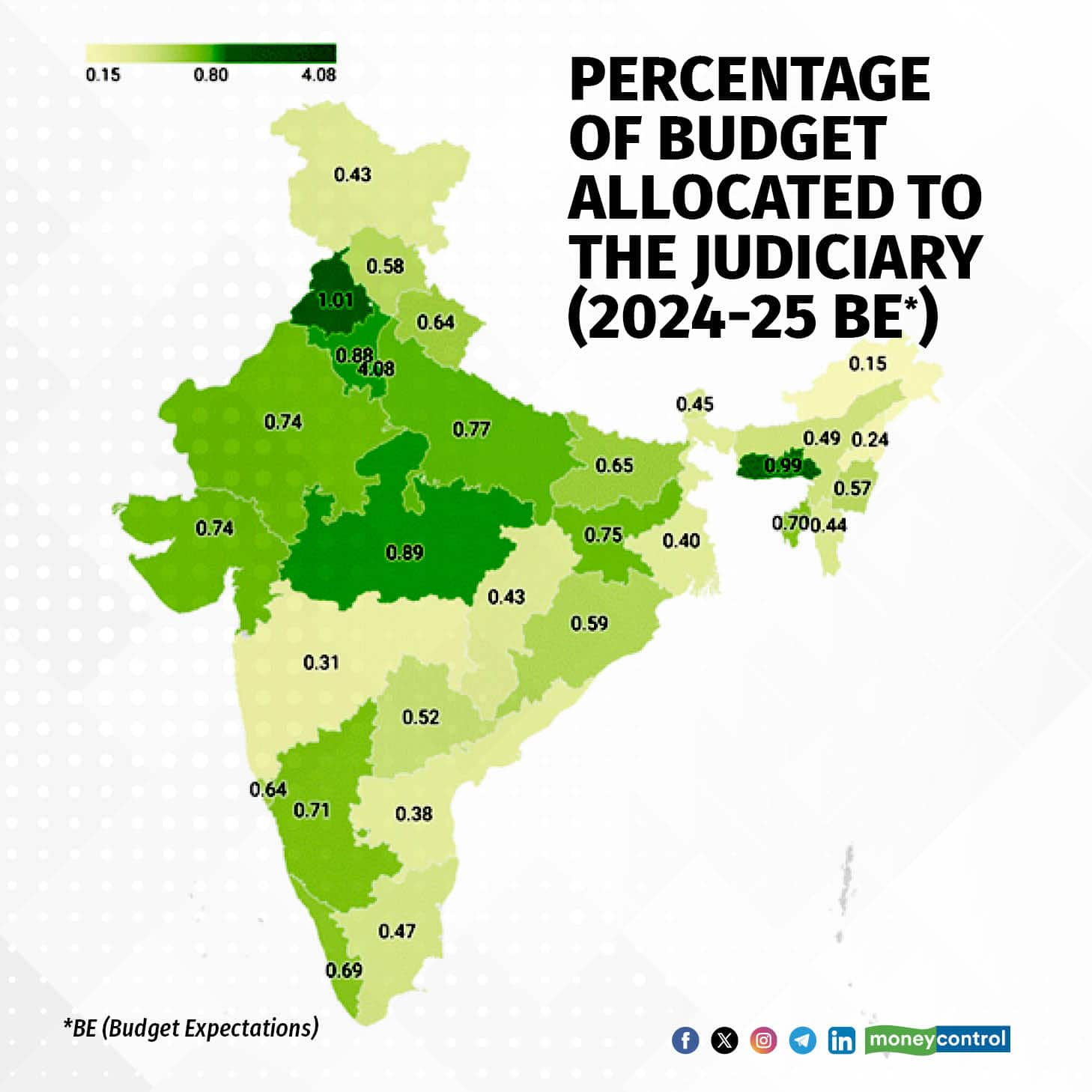

What is even more concerning is the vast disparity between states in budgetary allocation to the judiciary. Delhi allocated 4.08% of its budget to the judiciary, while states like Maharashtra and West Bengal allocated only 0.31% and 0.4%, respectively.

The above disparities also translate into differences in per capita judicial spending. Delhi allocated Rs 1,424 per person on the judiciary, while West Bengal and Uttar Pradesh allocated only Rs. 123 and Rs. 130, respectively.

Systemic Flaws in Budgeting Processes

The disparities in budgetary allocation to the judiciary do not merely reflect differing state priorities, they arise from fundamental flaws in how judicial budgets are planned and prepared. The courts in India have traditionally relied on incremental budgeting, where small adjustments are made to previous year’s allocations to arrive at current budgets rather than relying on scientific assessments of actual requirements. These budget requirements are then submitted to the respective Departments of Law and Justice in the various state governments and the Union government, respectively.

The current budgeting method follows the supply-side approach, which means the judiciary largely operates within the budget allocated by the executive. Although the judiciary engages with the executive in the budgeting process, the present approach of the incremental approach to budgeting has not allowed for a comprehensive alignment with the judiciary’s long-term functional and operational requirements.

An NCMS Committee led by Justice Badar Durrez Ahmed in 2012 had recommended a shift to demand-side budgeting based on comprehensive assessments of infrastructural needs, staffing requirements, and technological upgrades.

However, this recommendation remains largely unimplemented due to a lack of institutional capacity within the judiciary for systematic budget planning. This, in turn, perpetuates this cycle of ad-hoc budgetary allocation, which results in sub-optimal allocation of funds to the judiciary.

The Finance Commission as a Catalyst for Reforms

The Finance Commission, with its constitutional mandate to address fiscal imbalances and ensure equitable resource allocation for the delivery of basic public services across states, is uniquely positioned to address these systemic issues. Apart from its main mandate on deciding on the distribution of net proceeds of tax between the Union government and state governments, and also among the states themselves, the Finance Commission recommends grants-in-aid to states. These grants are a mechanism designed to ensure comparable levels of public service across states.

The 13th and 15th Finance Commissions had recognised supporting the judiciary as one of the most important means to improve governance. The 15th Finance Commission recommended grants of Rs. 10,425 crores for judiciary grants in 2020, for the construction and maintenance of Fast Track Special Courts. While this was a significant amount, the focus remained largely on physical infrastructure creation rather than institutional capacity building. It is important to note that recent studies have suggested that building more courts has not translated into a reduction in case pendency.

The 16th Finance Commission has an opportunity to pioneer a more holistic approach. Rather than simply recommending more funds for physical infrastructure, it should aid in addressing the root causes of judicial inefficiency, beginning with the lack of professional budgeting capacity within the judiciary itself.

The Commission should recommend grants for establishing budgeting practices initiatives with dedicated teams in each High Court and the Supreme Court. This initiative would comprise persons trained in modern budgeting methodologies, needs assessment methods, and strategic planning frameworks. This initiative would ensure that judicial budgeting represents the actual requirements of the courts. Additionally, the Commission should fund research offices within High Courts to enhance the judiciary's analytical capacity and to develop solutions for improving judicial processes.

The clocks of justice in India can tick faster with the right reforms. With thoughtful interventions from public institutions like the Finance Commission, it is possible to align public funding with the judiciary's operational needs. By addressing the issues of disparity in budgetary allocations and the need for improvement of the quality of public funding to the judiciary, the 16th Finance Commission can strengthen the rule of law itself. These pivotal interventions can go a long way in ensuring that justice is neither delayed nor denied.

(C.H. Rohith is a data analyst at DAKSH. This article draws from a paper co-authored with Surya Prakash B.S. Keerti Kumar provided research assistance.)

Views are personal and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.