“Cities are mankind’s greatest invention.”

So said Norman Foster, the architect behind Berlin’s Reichstag building and the Gherkin in London, on stage at a COP28 event on Saturday. It’s hard to disagree with the sentiment. There’s nothing quite like a diverse population packed into a dense area to foster innovation, cultural exchange and economic growth.

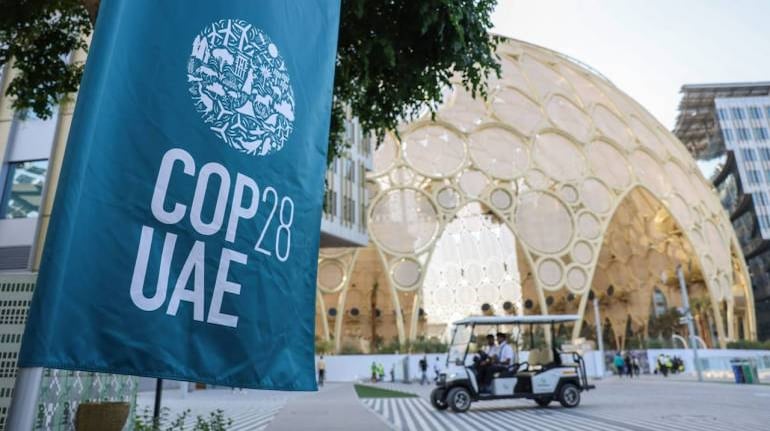

And here at the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Dubai, cities are a hot topic. It’s the first time subnational leaders, including mayors, have been given a formal role in the negotiation space with the two-day Local Climate Action Summit on Dec. 1-2, designed to highlight the role they play in driving down emissions. (Bloomberg Philanthropies co-hosted the event with the COP28 Presidency.)

In many ways, though, cities don’t always feel like mankind’s greatest invention. Home to more than half the global population — and set to house 70 percent of it by 2050 — urban environments are responsible for 75 percent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions, while air pollution kills an estimated 8 million people a year.

Yet there’s potential to create vibrant, low-carbon metropolises. Given the right powers and access to finance, city officials could be the key to accelerating our transition to a global, green economy.

London, for example, is home to 13.4 percent of the UK population but accounts for 10 percent of the UK’s carbon footprint as residents benefit from a world-class public transport system. Urban density opens up more options for low-carbon transport and heat networks; and it takes less energy to heat and power apartments than larger homes in the countryside.

If there’s potential for mitigation, there’s also a great need for adaptation. Throughout history, urban communities have withstood plenty of existential challenges — plagues, fires, wars — but the limit of their resilience is being tested by extreme weather caused by the climate crisis.

City leaders aren’t blind to these facts, with many exhibiting greater ambition than their counterparts at the national level. London’s mayor, Sadiq Khan, has led the way on clean-air regulation with the Ultra Low Emission Zone, while UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has watered down or delayed national net-zero targets. Bogotá, led by Mayor Claudia López, is spearheading Columbia’s transition to electric vehicles with a huge electric bus fleet. Her ambition helped the national government exceed its target this year for registered electric vehicles.

More broadly, C40 Cities, a network of nearly 100 mayors and city officials around the world, has a requirement that each member develop a robust science-based action plan for how they’ll meet the requirements of the Paris Agreement. Just having that plan puts many cities ahead of their nations. (Michael Bloomberg is president of the C40 board.)

Mayors are on the front line when it comes to their communities, which helps them make efficient, targeted decisions. They also play a role that’s not too dissimilar to chief executive officers. Urban centers compete with each other to be the most attractive place to live and do business. They want the best talent and investment, so they need to provide healthy, clean, enjoyable places for people to inhabit. That puts an extra impetus around environmental sustainability. As Mark Watts, executive director of C40 Cities, told me: “Ministers of national government, on the other hand, are more about creating legislation and setting long-term directions.”

The best ways to make a city nicer to live are congruous with climate action. Electric vehicles, public transportation and cycle lanes lead to cleaner air, quieter streets and less congestion. Greenery helps reduce the urban heat island effect (where infrastructure absorbs and produces heat, turning city blocks into baking ovens), draws down carbon dioxide, makes people happier and prevents flooding. Energy-efficiency measures reduce resident’s bills while lessening pressure on grids.

But it’s clear that more help is needed. Listening to mayors speaking at events over the last few days at COP28, the resounding theme on everyone’s mind is finance.

Even in wealthy countries, local communities are feeling the effect of penny-pinching. Speaking at a Chatham House climate change conference in November, Marvin Rees, mayor of Bristol, stressed that one of the hidden costs of austerity in the UK are the depleted back rooms of city halls. In April, Bristol City Council launched Bristol City Leap, an energy investment program that will see £424 million ($535 million) invested into renewables, heat networks, heat pumps and energy efficiency measures over the first five years. “It took four years to work out,” Rees said. “If we were starting at year zero, we wouldn’t be able to do it because we wouldn’t have the people or the funds.”

Efforts are being made to release funding for climate initiatives, as reflected in a series of blockbuster COP announcements from the United Arab Emirates and others. But Yvonne Aki-Sawyerr, mayor of Freetown in Sierra Leone and co-chair of C40 Cities, told me the challenge is getting the money to where it needs to go. Mayors are well-placed to spot vulnerabilities and figure out solutions — all climate impacts are felt locally — but the multilateral development banks that distribute a lot of the money are designed to work with nation-states, not with subnational actors.

Mayors would benefit from having the right powers. One of Freetown’s climate initiatives is the “#FreetownTheTreetown” program, which aims to plant — and grow, as Aki-Sawyerr stresses — a million trees. Mass deforestation in the city left it exposed to the effects of water runoff and in 2017, that vulnerability became a disaster when floods and landslides tragically took the lives of more than 1,000 people.

The tree-planting program has been a success, with tree survival rates at 82 percent and 1,500 young people employed to track each tree’s progress, according to Aki-Sawyerr. But Freetown’s ability to choose its own fate is being hampered because the city council doesn’t have full control over issuing building permits. So while the council might prioritize an area for tree planting in order to stabilise a steep slope, someone might be able to get a permit to build a house there instead. Aki-Sawyerr explained: “The disaster that follows is not just the cutting of the tree...[but] the landslide.”

Elsewhere, Watts tells me mayors are keen to push ahead with their own clean-air zones, following London’s ULEZ example or building regulations. But they need the powers and the finance flows to do so.

The risk of public backlash, as experienced during London’s ULEZ expansion, shouldn’t be dismissed. NIMBY-ism is already stymieing the renewables rollout in many rural areas. But if the impacts of climate change are felt locally, then so are the benefits of low-carbon initiatives. City officials are in the best place to engage with their people, ensuring a just transition that benefits everyone.

There’s a lot of talk about the sacrifices we’ll have to make in the climate fight: eating less meat, taking fewer flights, consuming less stuff. But what’s exciting about the discourse around cities is the potential to make them better. Better for economic opportunities. Better for human health. Better for the planet.

Lara Williams is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. Views do not represent the stand of this publication.

Credit: Bloomberg

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.