US consumer spending surged at a 4 percent annual rate last quarter even after accounting for inflation — and inflation is rapidly slowing. But say anything good about this economy and expect intense pushback. Yes, there are too many Americans living paycheck to paycheck and without any financial buffer, but there are far fewer than before the pandemic. The real net worth of a typical family jumped 37 percent from 2019 to 2022, which is the largest increase over a three-year period on record and was nearly universal across all demographic and economic groups.

One would think that all the spending, the additional wealth and an unemployment rate holding below 4 percent since early 2022 would merit a mention when people talk about the economy. But they rarely do.

Instead, Americans are deeply pessimistic, with over 40 percent more people expecting the economy to be worse in the next five years than better. That’s even gloomier than in the aftermath of the global financial crisis and Great Recession in 2010, when unemployment exceeded 9 percent. This is a problem because all the pessimism could become self-fulfilling if consumers retrench out of concern for what may lie ahead or businesses hold off on investments.

So, what is going on? And why is pessimism worse than at times when the economy was objectively worse, like in the 1970s and early 1980s? The answer is a toxic brew of bad events, not the least of which are the media feeding the human tendency toward the negative and social media spreading bad news faster and wider than ever before. Social media, which began in earnest in the early 2000s, could help explain why current views are more negative than today’s economic conditions would have predicted in the past.

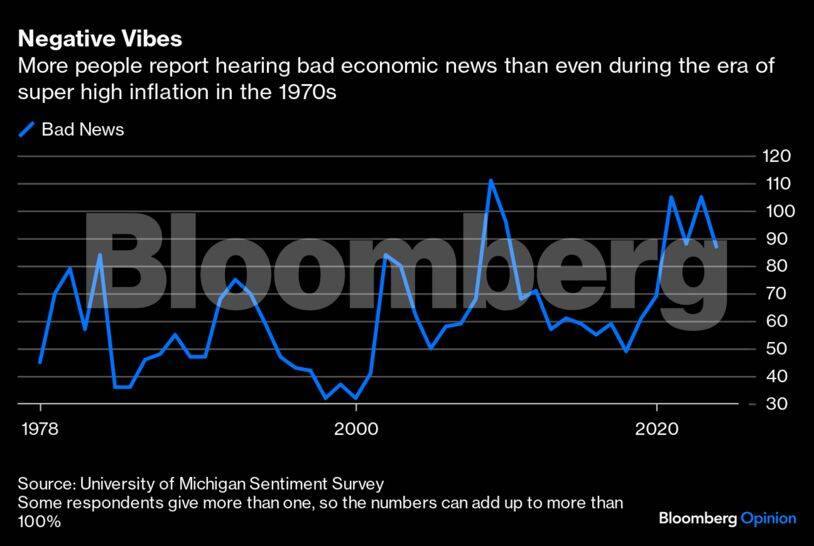

During the past four years, we have lived through a series of negative events, including the pandemic, economic shutdowns, very high rates of inflation, the war in Ukraine and surging interest rates. But their effect on economic expectations is being amplified more than usual and overshadowing good events such as the rapid labor market recovery. Last year, respondents to a long-established survey were far more likely to report having heard bad economic news than respondents in 1980, even though the so-called misery index — the inflation rate plus the unemployment rate — was almost twice as high back then.

Social media has become a more important medium for how people get their news. Half of US adults get at least some news from social media sites, according to Pew Research Center. The most popular sites for news, Facebook and YouTube, have a massive reach of a third and a fifth of US adults, respectively.

One concern is that social media amplifies bad news over good news, according to research by Andrea Bellovary, a data scientist at Nielsen, and her co-authors. Tweets by 44 news organisations they studied from 2018 to 2020 were significantly more negative in tone than positive. The negative tweets got more engagement in the form of likes and sharing. The patterns were similar for news organisations of different political leanings. Other research shows negative content on social media in general spreads more widely, fueling the gloomy mood.

John Hopkins University professor of economics Chris Carroll argues that beliefs about the economy spread in an “epidemiological” process. Here, news coverage that includes the views of professional forecasters can shape people’s expectations, such as about future inflation or unemployment. But not everyone checks the news, so social contact with others about the economy can spread views too. The faster the transmission, the more rapidly economic developments affect expectations and actions. Applying his framework, it’s clear how social media, where news “goes viral,” can be an accelerant.

But that’s no guarantee that today’s heightened pessimism, as disconnected from overall economic conditions as they are, translates to cautious behaviour like cutting back on spending or not asking for a raise. But if social media is pushing a wedge between economic expectations and the economic reality, then measures of expectations could become more useful for the Federal Reserve and forecasters. That’s certainly been the case the past few years with extra gloom but strong spending.

Surveys asking people how they feel about the economy and where it’s headed — often referred to as “soft data” — can be instructive. Consumers “called” the Great Recession in 2007 before the professional forecasters. The so-called “hard data,” like GDP, did not show the weakness at the time, but eventually did after revisions. The wedge between the hard and soft data after the pandemic is large and persistent, which cautions against leaning hard on expectations. But that’s exactly what the Fed does when thinking about inflation. Here’s what the central bank said in a statement after its last policy meeting on Sept. 20:

The Committee’s assessments will take into account a wide range of information, including readings on labour market conditions, inflation pressures and inflation expectations, and financial and international developments.

The economy is strong, and there’s no recession in sight despite the gloom. So, what dials down the amped-up pessimism about the economy? More good news is insufficient. It will take less bad news.

Claudia Sahm is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. Views do not represent the stand of this publication.

Credit: Bloomberg

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.