In what might be the biggest overhaul of the expense ratios that mutual funds have charged investors since 2018, the capital market regulator came out with a detailed set of fresh proposals on May 18.

The proposals of the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) aim, broadly, to make the total expense ratio (TER) more transparent and true-to-label (what you pay is what you get), bring about economies of scale (for retail investors, just as funds have brought it about for large investors through debt funds), bring in new investors, and discourage distributors and fund houses from churning investors from one scheme to another.

Every proposal in the 40-page consultation paper is backed by research and findings from a study that SEBI initiated in December 2022. Here are the big numbers behind SEBI’s proposals that could make mutual funds cheaper and more transparent for investors.

Has the expense ratio narrowed over the years? Only for a few

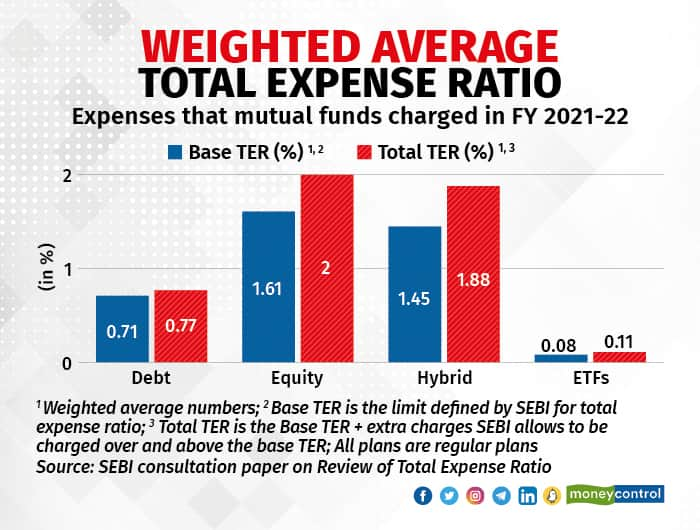

The basic premise for expenses that funds charge is this: as a scheme grows in size, it should charge less. But have expense ratios really gone down for investors? The SEBI study showed that it hasn’t gone down as much <See: Weighted Average Total Expense Ratio>.

Weighted Average Total Expense Ratio. The total TER charged by the fund house is the base TER + extra charges.

Weighted Average Total Expense Ratio. The total TER charged by the fund house is the base TER + extra charges.

SEBI pointed out that the Rs 40-lakh crore Indian MF sector has grown over the years, with its asset size going up to Rs 39 lakh crore in February 2023 from Rs 6 lakh crore in March 2012. The number of investors has gone up 2.94 times and the number of folios has increased 2.63 times from March 2017 to March 2023. But, it said, expenses haven’t gone down as much for retail investors.

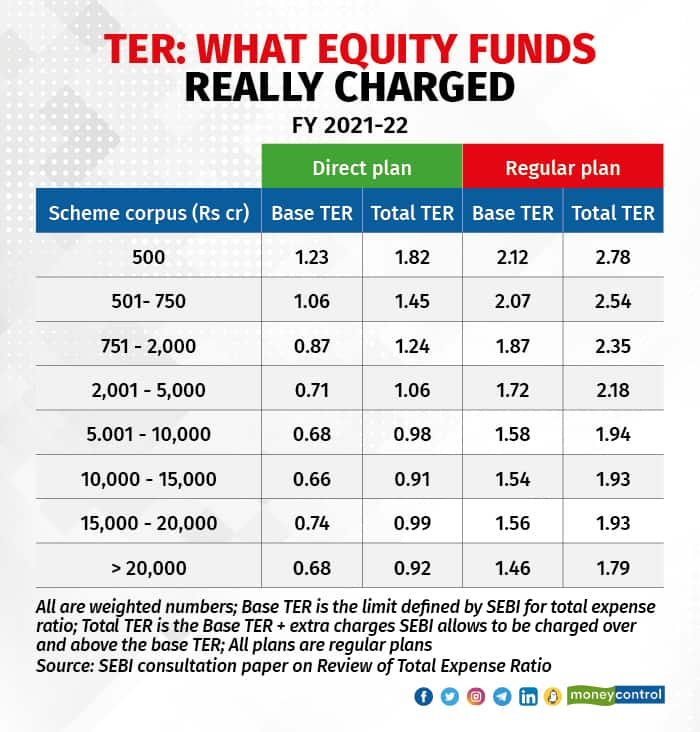

Digging a bit deeper, SEBI observed that the way mutual fund schemes charge expenses to investors is not as transparent as it ought to be. This is partly due to SEBI’s policies, which it now wants to reconsider. Here’s how your fund house really charges.

Aside from the slab-based TER framework as per SEBI’s rules (also called the Base TER), the regulator allows fund houses to levy certain other charges over and above the Base TER. They include a 0.12-percent brokerage, 0.05-percent exit load, 0.30-percent additional commission to distributors for getting inflows from smaller towns, goods & services tax on investment advisory fee, and securities transaction tax (STT). All these charges pushed the Total TER way above the Base TER prescribed by SEBI <See: TER: What Equity Funds Really Charged>.

The total TER charged to the fund is- in some case SEBI noted- as much as the base TER

The total TER charged to the fund is- in some case SEBI noted- as much as the base TER

While most MF officials said a more transparent TER is good, taxes such as GST and STT should be kept out.

“The government decides STT and GST. If the rates go up sharply tomorrow, how will the MF industry cope?” asked a veteran mutual fund official.

The good news, said a second fund house chief, is that SEBI has proposed an increase in the Base TER to 2.55 percent, up from 2.25 percent now. That’s for equity funds. For debt funds, the second official added, it’s a bit of a dampener. The new peak TER rate proposed is 1.20 percent, down from 2 percent.

“This puts debt funds at a disadvantage. When interest rates start to go down, duration funds will become a popular choice. To be able to sell them at the right time, we need to incentivise the distributors. But a reduction in the TER for debt funds will make it difficult for fund houses,” the second chief said.

All the officials who spoke to Moneycontrol requested anonymity because they and the Association of Mutual Funds of India are still preparing their formal responses to SEBI’s proposals. AMFI declined to comment, as per an email it sent to Moneycontrol for a story published a day before this one.

Can a fund house pay for research?

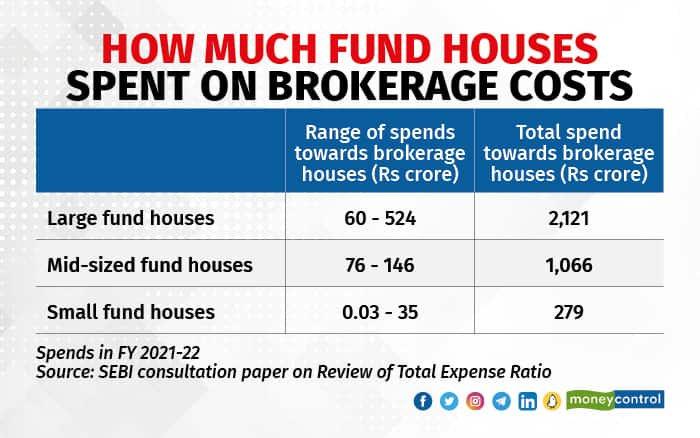

SEBI found in its study that fund houses spend an inordinate amount on research provided by brokers. However, SEBI noted that the 0.12-percent brokerage fee that MF schemes can charge investors included the brokerage fee for buying and selling securities and the money paid for research. This, it noted, hiked up the TER by a wide margin in some cases.

According to SEBI’s analysis, fund houses paid almost Rs 3,500 crore towards brokerages in FY22 <See: How Much Fund Houses Spent on Brokerage Costs>.

Funds houses pay brokerage costs, a part of which they can charge to the scheme.

Funds houses pay brokerage costs, a part of which they can charge to the scheme.

This proposal has divided fund houses. The veteran chief said the amount SEBI highlighted is “staggering.” It could also lead to corruption, he said.

He cited the example of large-caps stocks, where the brokerage was negligible because there was ample liquidity and no real expertise was needed to execute transactions. Here, he added, a dealer can choose a broker who can pass on a kickback back to the dealer. Or worse, could front-run the scrips.

The NFO game: Nipping churning in the bud

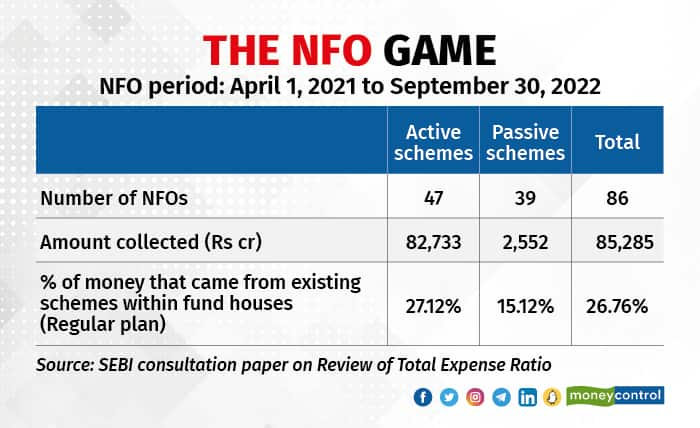

Where do mutual funds get all the money for their new schemes?

In a startling discovery, SEBI found that of the 86 new schemes that fund houses started from April 2021 to September 2022, almost 27 percent of inflows came from existing schemes in-house.

SEBI believes that NFO inflows arising out of switches from existing schemes within fund houses might be an unnecessary churn and should be disincentivized if done for the wrong reasons.

SEBI believes that NFO inflows arising out of switches from existing schemes within fund houses might be an unnecessary churn and should be disincentivized if done for the wrong reasons.

In simple words, some distributors nudged investors to switch from an existing scheme to a new fund launched by the same fund house. New schemes, on account of their small size at the inception stage, tend to pay higher distributor fees than existing, albeit much larger schemes, where the ability to pay distributor commission is limited.

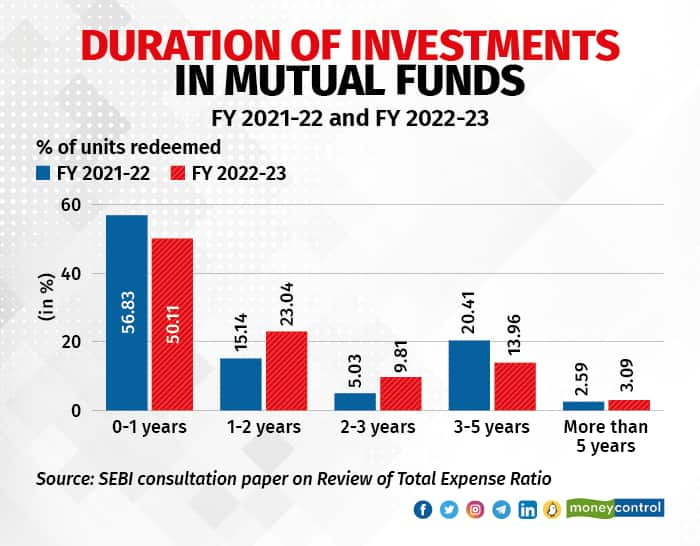

There’s a bigger evil that arises out of such churning: investors don’t stay invested for the long term <See: Duration of Investments in Mutual Funds>.

Mutual funds are for long-term investments, yet some churn happens that lead to pre-mature redemptions.

Mutual funds are for long-term investments, yet some churn happens that lead to pre-mature redemptions.

SEBI found that 50 percent of the assets that were redeemed in FY23 stayed invested in funds for just under a year and 83 percent of the assets that were redeemed in FY23 stayed invested for not more than three years.

Now, SEBI has proposed that if distributors switch their clients’ money from one scheme to another, distributors should get paid the lower of the two schemes’ commissions. Fund houses said that while this is largely fine, it should make an exemption for systematic transfer plans (STP).

An STP is a facility where investors can park a lump sum in a debt fund and then move systematically – every month – to an equity fund within the same fund house. It works like a systematic investment plan (SIP) but parking money initially in a debt fund can earn slightly higher returns than a savings bank from where a SIP goes out.

“An STP is a great product. SEBI shouldn’t kill it,” said the second MF chief.

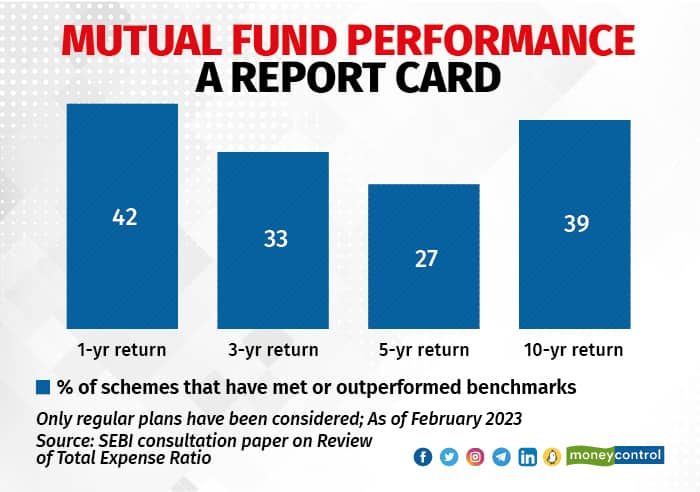

Should fund managers charge less if they underperform?

The struggles of active-managed equity funds in recent years, versus their benchmark indices, wasn’t quite a secret. But the numbers that SEBI put out in its consultation paper are still startling. Analysing the performance of actively managed schemes, SEBI observed that only 40 percent of them outperformed their benchmark indices over the past 10 years <See: Mutual Fund Performance, a Report Card>.

Large-cap oriented mutual fund schemes have struggled to beat their benchmark indices

Large-cap oriented mutual fund schemes have struggled to beat their benchmark indices

Most fund houses said that while the proposal is good on paper, it is almost impossible to implement. Another fund house's chief explained that fund houses have to calculate the performance and net asset value (NAV) for each investor and then calculate how much investment management fee to charge. For this, each fund house will have to look at the tenure of investment. This, he explained, would be a costly exercise.

The second chief foresees another challenge. He said if the performance-based fee rule is implemented, it might put pressure on fund managers to churn or take additional risks.

“Say, a fund manager follows a buy-and-hold strategy and has designed a portfolio keeping the next three to five-year period in mind. But if the fund underperforms over the next two or three quarters, he can face immense pressure to take risks and correct his performance, notwithstanding his core strategy."

SEBI has asked for public comments on its proposals by June 1.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.