Part 29 of the Moneycontrol Classroom goes into the very basics of what an index is and the purpose it serves.

I keep coming across articles that talk about the movements of the Sensex and the Nifty. What are they?

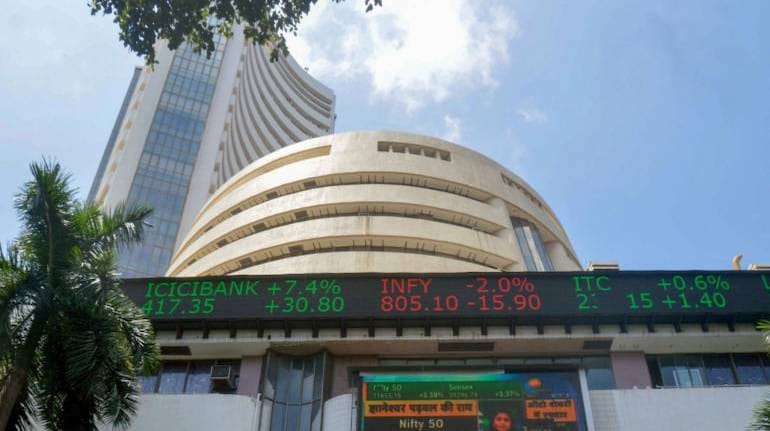

The Sensex or the Nifty are a sort of a virtual portfolio of the country’s largest stocks that have been created by the BSE and NSE, respectively. The Sensex has 30 and the Nifty 50 stocks. Even within that list, more weightage is given to the larger stocks.

Though the Sensex and Nifty contain a small number of stocks compared to the 2,000 (NSE) or 5,000 odd (BSE) companies listed on the exchange, the companies in the index account for a majority of the entire market’s value. It is for this reason that the performance of the Sensex or the Nifty is often characterised as the market's performance (even though that is not always accurate, as we will learn).

Tell me more about how an index works.

During market trading hours, the levels of indices such as Sensex and Nifty are calculated and published in real-time, based on the performance of the underlying stocks.

Assume an index contains only two stocks – Stock A and Stock B -- each having 50 percent weightage. If stock A is down 1 percent while Stock B is up 1 percent, the index will be unchanged. Formula: [(1% x 0.5) + (-1% x 0.5)] = 0. But if Stock A had 75 percent weightage while Stock B had 25 percent, the index would have been up 0.5% [(1% x 0.75) + (-1% x 0.25)]. So when the Nifty is, say, up 1 percent, that number has been arrived at by doing exactly the above calculation after considering the changes in all 50 of its constituents and their weightages.

What about the levels of an index that is widely reported on. If the Sensex hits 40,000, what does it mean? Is the Sensex at 40,000 better than Nifty at 12,000?

Those are just absolute levels that allow for easy tracking of the index's performance. When the index is first created, its price is set at a base number, say, 100. From there, the level is dictated by the performance of the underlying stocks.

The Sensex at 40,000 (or the Nifty at 12,000) in and of itself does not mean anything. The number will have to be looked at in the context of its performance: if it has risen from 38,000 to 40,000 in a week, it means that the country’s top stocks have risen, on average, a little over 5 percent.

You could evaluate the index's valuation by calculating its price-to-earnings (PE) ratio. This can be done dividing the price to the index's earnings per share. An index's EPS is also nothing but the weighted-average EPS of its constituents (the data is published by the exchanges). So if the Sensex is at 40,000 and its EPS last year was Rs 1,450, its PE ratio is 40,000/1,450 = approx 27.

The historical average PE ratio is around 15. So if an index is trading above that, it may be concluded investors are optimistic about earnings growth (a larger denominator in the PE ratio would normalise the number). If the earnings growth does not come through, stocks could face the risk of correction (smaller numerator causing the same effect).

If the index is trading a record high, does it mean the economy is doing well? Conversely, the Nifty/Sensex have crashed, does it mean the economy is struggling?

It’s a bit more complicated than that. Stock prices (and so indices) are driven by demand and supply, which in turn, are driven by how people feel about future prospects of companies (among other things). But it must be remembered that such feelings are often driven by emotional biases such as greed and fear.

So while generally, you could say that a rising market means investors expect companies (and perhaps the economy) to do well in the near future, such assessments may not always prove to be correct.

One should also not read too much into a short-term but strong reaction in a particular direction to an immediate news piece. Before long, the market could shrug off the news and continue in the opposite direction.

What else should I know?

Because an index is considered to be a gauge of the performance of a particular part of the market, it can be used to understand which segment is doing better than the other.

For instance, there are various sector indices, which contain only companies from that sector. You can instantly know that bank stocks have generally done better than auto stocks by comparing the performance of the bank and auto indices.

Similarly, there are indices, which contain only medium-sized (midcap) or smaller-sized (smallcap) companies. There are times when small stocks do better than large stocks and vice versa. To know this, look up the performance of the Sensex versus the smallcap index.

What this means is that if you invested in midcap stocks (or funds), which took a beating -- as happened in early 2019 – your own portfolio will be bleeding even as frontline indices such as Nifty or Sensex (driven by large stocks) may be doing well.

Also, remember that the movements in the heavyweight stocks influence trends in the indices. So if the five largest stocks in an index post big gains, the index will rise even if the rest of the stocks in the index are struggling. Conversely, steep falls in the top five heavyweights could drag down the index even if the rest of the stocks are doing well.

How are stocks selected for an index?

There are quite a few parameters like a stock’s liquidity, market cap and how much of the company’s shares are held by the public (free-float). Generally, stocks are selected in order of market cap – higher the market cap, higher the weightage.

Since stock prices (and hence market caps) change all the time, they also affect the weightages of a particular index. So after a pre-defined period, those who manage the index will rebalance the portfolio to moderate weightages. They will also add or drop a particular stock to or from an index, as it may no longer meet the index’s methodology.

Can I invest in an index like the Sensex?

Good question. Technically, you can construct your own portfolio whose constituents match exactly the weightages in the index. But that would be a cumbersome exercise. If you have only Rs 1 lakh, and say Reliance Industries forms 10 percent of the Sensex, it would be difficult to buy Reliance shares for exactly Rs 10,000. Secondly, indices keep getting rebalanced periodically. Would you be able to keep up?

Fortunately, the financial industry has come up with products such as index funds that allow investors to seek exposure to a portfolio resembling a particular index. That is because it is easier for a fund having Rs 1000 crore of pooled money to buy Reliance shares worth Rs 100 crore, and distribute commensurate units of the fund to its investors.

I read an article that said that if you invested Rs 10,000 in the Sensex 25 years ago, your returns have multiplied x times. That’s just a theoretical study, right? Or did index funds exist 25 years ago?

Partially correct. It may have been difficult for an investor to “invest in the Sensex” 25 years ago. But the idea is to generally drive home the point that investing in top stocks and leaving them alone generates good returns.

Thus, if you started investing 25 years ago, and kept investing in the best companies of the time, your returns would probably have been close to the returns that the Sensex has clocked.

So I should invest in the Sensex or the Nifty, right?

The advent of index funds (or ETFs) makes it easy to “buy” an index. What’s better, indices have a growth bias. That is if a large company has fallen out of favour, it will automatically be dropped from the index during the periodical rebalancing, to be replaced by a better performing company. As a result, your portfolio will always be safe from companies that are stagnating.

What other purposes do the indices serve?

Indices help compare performances of various portfolios. Hence they are also called benchmarks. So if you invest on your own, you could compare the performance of your portfolio to the leading benchmarks such as the Sensex or the Nifty. If your own portfolio fails to beat the index’s performance, would you not have been better off investing in the index?

Many retail investors that buy and sell stocks on their own based on limited research or a friend’s advice (or worse, market “tips”) would do well to carry out the above exercise. The results, especially over the long term, may surprise you.

Now let's look at the benchmarking concept in the context of a mutual fund. Fund managers take your money and invest in stocks as per their own research and understanding. The aim is always one: that the mutual fund portfolio does better than a comparable benchmark (say, the Sensex or the Nifty for a largecap mutual fund, or the mid or small cap index, for a fund that invests in midsize or small companies).

Should the fund manager consistently fail to beat the index, you need not stay invested in the fund – you are getting worse returns than the index, and paying the fund company fees to invest money on your behalf.

Are you then suggesting that buying an index is better than investing in mutual funds or directly buying stocks?

At a very basic level, any direct investment in a stock is a bet by an investor that their portfolio will do better than the index. And that the investor is not satisfied by the performance of an index, which, over the long term, has been extremely good in India (generally 12 to 15 percent compounded).

As for investing in index funds versus actively managed mutual funds, the concept of index investing has become a wildly popular concept in the west, after studies have shown that most fund managers have been failing to outperform indices for a long time (after adjusting for fees).

In India, index funds are not very popular as so far, mutual funds often comfortably beat benchmark indices. The reasons for funds’ outperformance in India (or underperformance in the West) can be complicated and subjective, so we will avoid going into those. But it must be mentioned that lately, it has been seen that many funds in India have also failed to beat indices.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.