The United Nations' State of World Population 2023 report said on April 19 that India would overtake China to become the world's most populous country by the middle of the year. Crucially, it noted that a massive 68 percent of India's population falls in the 15-64 age group, which comprises mostly of working-age individuals.

While China had a similar percentage in the 15-64 bracket – 69 percent, to be precise – 14 percent of its population is older than 65 years compared to 7 percent for India.

"As the country with the largest youth cohort – its 254 million youth (15-24 years) – can be a source of innovation, new thinking and lasting solutions," said Andrea Wojnar, the United Nations Population Fund's representative for India.

Indeed, India's burgeoning working-age population has been seen as a source of opportunity for several years now.

In a speech last year, Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Deputy Governor Michael Patra referred to the country's demographics as one of the four engines "that can power India…towards becoming an economic superpower".

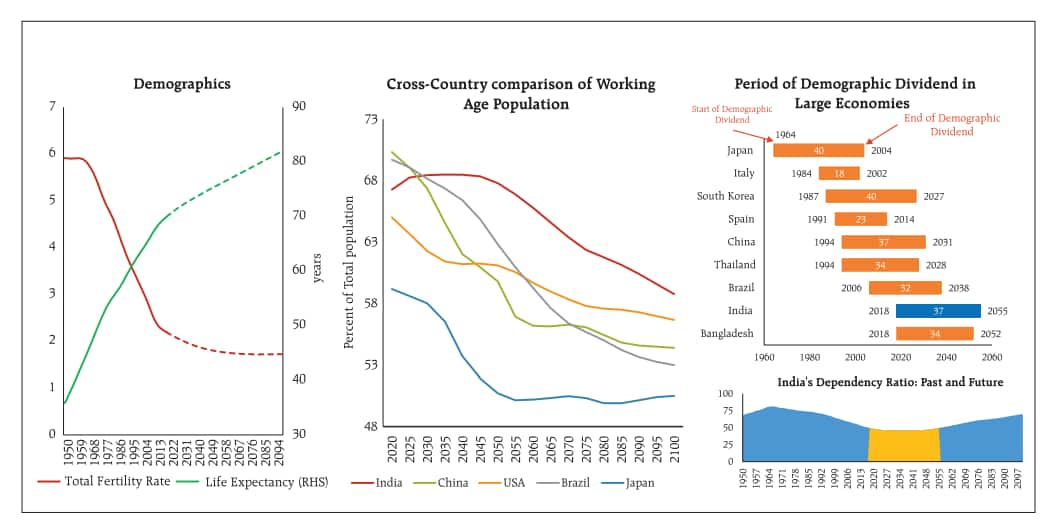

Comparing India's working-age population ratio with that of China, Brazil, the US and Japan, Patra pointed out India's advantage — a working-age population ratio that will keep rising till 2045.

Source: RBI

Source: RBI

"Making the most of this demographic dividend is India's opportunity as well as a challenge," he added.

The challenge is very well upon us. And India risks seeing this dividend cancelled.

Fewer salaried Indians

A key to encashing the demographic dividend is the creation of an adequate number of jobs.

While the unemployment rate has come down sharply from the peak it hit early in the pandemic, that decline does not tell the whole story.

According to the government's Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS), the percentage of rural males employed in salaried jobs fell from 14 percent in 2017-18 to 13.6 percent in pandemic-hit 2020-21. For urban males, the decline has been similar: from 45.7 percent to 45.3 percent.

But females have seen a much larger drop in salaried employment: from 10.5 percent to 9.1 percent in rural areas and 52.1 percent to 50.1 percent in urban areas.

But if the unemployment rate is falling, where are these formerly salaried Indians going?

Back to the farm

According to Pronab Sen, former chief statistician of India and head of the Standing Committee on Economic Statistics, the PLFS data indicates that the number of agricultural workers was 5 million higher in 2021 compared to 2016.

"The most striking feature of what's been happening since 2017 is that for the first time in 30 years, the number of workers in agriculture has gone up. We saw 30 years of sequential decline in the number of people engaged in agriculture. It's gone up now — and not gone up by a small amount. It's gone up by nearly 5 million people, which is not a joke," Sen said in a panel discussion in late December.

In 2017-18, about 44.1 percent of workers were employed in agriculture. This figure stood at 46.5 percent in 2020-21.

"The most plausible interpretation of these facts is that the quality and number of non-agricultural jobs on offer has regressed," a column co-authored by former RBI governor Raghuram Rajan, said in December.

"If so, we may be the only developing country that is pushing people back to agriculture, an alarming indictment of our efforts at job creation," Rajan and his co-authors added.

Bloated agriculture

As mentioned by Pronab Sen, workers started returning to agriculture much before the coronavirus pandemic struck. But why?

According to former Reserve Bank of India deputy governor Viral Acharya, the reversal mentioned by Sen coincided with the collapse of the Indian housing market sometime in the middle of the last decade.

"And I conjecture that was a pretty important event for shifting of labour back into the rural areas. Housing markets have huge multiplier effects," Acharya said.

The improvement in India's food security has also contributed to the creation of agricultural jobs, Acharya posited, although the role played by the government’s subsidies — implicit and explicit — could not be ignored.

"There is power, water, fertiliser (subsidies)… So, our agriculture is likely to be bloated for that reason," the former central banker added.

Post-pandemic urgency

The coronavirus pandemic has infused an urgency into the government's actions. Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched a nationwide employment drive late last year. This followed the controversial Agnipath scheme, launched earlier in 2022.

But India's job problem precedes the pandemic.

"Though the Indian economy is supposed to enjoy the fruits of demographic dividend and achieve high growth rates but the recent trend of falling employment elasticity (just 0.07 during 2003-2011) paints a very disappointing employment scenario," an October 2016 paper, titled 'Structural Changes in Employment in India, 1980-2011', had noted.

Employment elasticity measures the change in employment when economic growth changes by one percentage point.

The paper (PDF), prepared as part of a research project at the Delhi School of Economics' Centre for Development Economics, noted that between 1980 and 2011, employment growth in India was primarily driven by the construction and services sectors.

| Employment growth rate (in percent per annum) | ||||

| 1980-93 | 1994-2002 | 2003-11 | 1980-2011 | |

| Agriculture, forestry, and fishing | 1.44 | 0.52 | -1.12 | 0.43 |

| Mining and quarrying | 4.27 | -0.78 | 0.87 | 1.82 |

| Manufacturing | 2.18 | 2.24 | 1.23 | 1.92 |

| Electricity, gas, and water supply | 4.39 | -1.63 | 2.84 | 2.19 |

| Construction | 5.79 | 6.60 | 9.08 | 6.98 |

| Services | 3.73 | 3.29 | 3.00 | 3.39 |

| Total economy | 2.09 | 1.57 | 1.04 | 1.63 |

"For 'modern' manufacturing industries and service sector industries higher skill sets would be required to benefit from demographic dividend," the paper added.

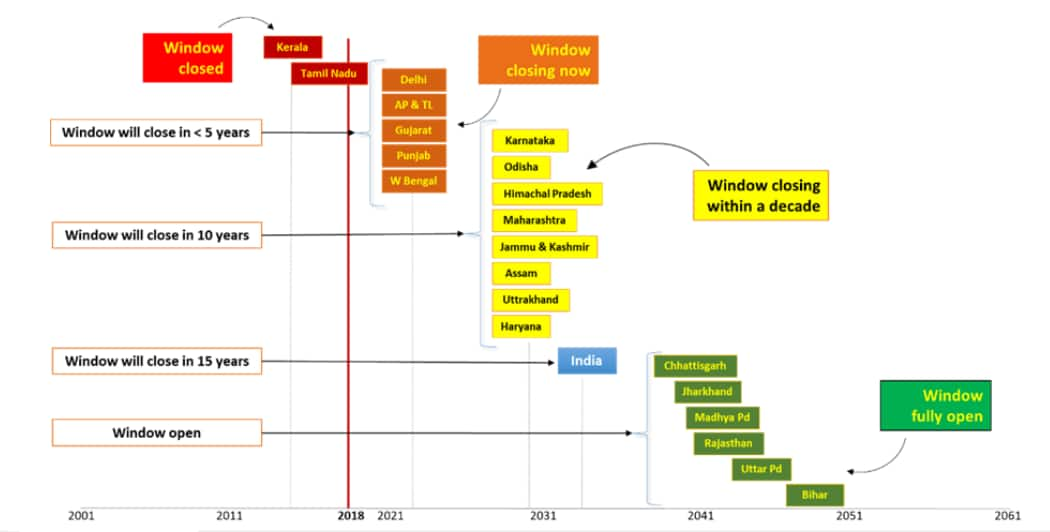

If the government's current focus on boosting manufacturing sector employment is to bear fruit, it must act quickly.

Source: UNFPA India

Source: UNFPA India

As the above chart shows, the demographic dividend window for Kerala and Tamil Nadu has already closed. A bunch of key states — Delhi, Gujarat, Punjab, West Bengal, Telangana, and Andhra Pradesh — will see their opportunity closing in the next few years. It is a race against time that India cannot afford to lose.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.