We seldom think of plants as major movers in world events. This, despite the fact that the colonial histories of sugar cane, indigo, opium, nutmeg and other spices are well-known, as is the colonial switch to plantation agriculture to grow commodities from tea to teak. Even less-discussed today, is the study and movement of native plants – ornamental or medicinal – for European gardeners, nursery owners, and scientists during colonial times. An art exhibition and a new book from Harvard University Press, seek to correct this to some extent. The art show, titled ‘A Treasury of Life: Indian Company Paintings c. 1790-1835’, is on at DAG in central Delhi till June 28. And the book, titled ‘The Lost Orchid: A Story of Victorian Plunder & Obsession’ by Trinity College literature professor Sarah Bilston, released on May 6.

Orchid with a historySarah Bilston’s ‘The Lost Orchid’ starts in December 1816, with the arrival of naturalist William Swainson in “Recife, on the coast of Pernambuco” in Brazil. Swainson is on a mission, to find and ship back exotic species of plants and animals to Europe where financiers as well as scientists are waiting for new discoveries.

(Image: Harvard University Press)

(Image: Harvard University Press)In journal entries that he made between Recife and Rio in 1816-17, Bilston writes that Swainson reports collecting "760 specimens of birds (including 'two or three new toucans') and more than 20,000 insects... He took drawings and descriptions of '120 species of fish, mostly unknown,' and sent seeds of many plants to Kew and other botanic gardens." Swainson also records donating an "'interesting collection of parasitic plants (orchids were thought to be parasitic then), together with another of cryptogamia'... to his good friend, Mr. William Hooker, Esquire of Suffolk."

Somewhere in this “donated” set, Bilston explains, was a rare orchid that would launch a massive competition among “European plant hunters like William Digance and Claes Ericsson” that would last for the better part of the 19th century. The contest was to find the precise location of this orchid, and to ship it back to Europe for urban gardeners who were keen to signal both their wealth and their sophistication in an increasingly globalizing world.

The “lost orchid” of Bilston’s book title is the Cattleya labiata or ruby-lipped cattleya, a purple blossom of “transcendent beauty” – according to an 1837 illustrated article in the journal ‘Floral Cabinet’ – that those in the business of selling plants used to drum up the 19th century craze for orchids in Europe.

The way that Bilston tells it, the story of how this particular orchid was "lost", desired and found again, is one of adventure and science as much as commerce. It's a story that spans continents as well as decades and disciplines - unfolding across science journals, gardening magazines, advertisements, colonial gazettes, and business rivalries between Europe's biggest plant traders who then commissioned the most dogged "plant hunters" to travel to the interiors of South America in search of a plant that may have travelled to Europe by accident the first time around - and then, just in time to flower. It's also a story that could only occur at the height of colonialism.

“Plant hunting,” Bilston writes in the prologue to ‘The Lost Orchid’, “required cunning, resilience, and a seemingly unshakeable sense of entitlement to the resources of other nations. Locating plants new to Europe, removing them and transporting them across continents, required hunters to journey vast distances, spy on competitors, identify (and harass) locals with knowledge and expertise, hire work teams, hack apart trees, pack up living plants for arduous journeys, and interface with networks of bankers, merchants and shipping agents.”

Bilston examines multiple angles of the trade in new (to the hunters) and exotic plants in her 390-page book: Colonial histories, science, marketing, advertising, business, the growing use of illustrations in the media, travel technology, the relationship and – unacknowledged – flow of knowledge and materials from the colonized to the colonizers, how the British managed to plant-hunt in Portuguese colonies in South America, the rise of fakes, a history of urban gardening, and the ambitions and careers of European business-owners who manufactured the orchid-mania to get rich off it in the 19th century.

In tracing the journey of this one species from the colonized world to the colonizers' homes in ‘The Lost Orchid’, Bilston paints a composite picture. There's a look back at how the Raj gathered riches and curiosities around the world and brought them to Europe. But there's also a look at commerce, and how the growing market paid for advances in science - from greenhouse technology and research into orchids which until then were thought to be parasitic, to how to transport live plants over long distances.

The plant species that made it to England alive during this period, often found a home in Kew Gardens in London. A ticket to the popular tourist spot today costs at least GBP 11 (prices vary depending on the month and time of visit and whether you buy tickets online or offline). Researchers today can see not just the plants at Kew, but another interesting import of the British Raj: botanical illustrations of species endemic to the countries that Britain and other European countries had colonized. The DAG show ‘A Treasury of Life: Indian Company Paintings c. 1790-1835’ would not have been possible without the latter.

Inside Kew Gardens, London. (Photo by Diliff via Wikimedia Commons 3.0)Plants in paintings

Inside Kew Gardens, London. (Photo by Diliff via Wikimedia Commons 3.0)Plants in paintings“There are rhododendrons and hydrangeas everywhere you go in the UK,” says art historian Giles Tillotson who’s been senior vice-president of exhibitions at DAG (formerly Delhi Art Gallery) since January 2021. We are talking after a walkthrough of the exhibition, ‘A Treasury of Life: Indian Company Paintings c. 1790-1835’ at the gallery on Windsor Place, just behind the Lexus store.

Rhododendrons, once native to England, had suffered a setback in the region following the ice age, and made a comeback when plant hunters brought specimens back from the Himalayas, among other places, centuries later. The flowering tree is among the many plants to successfully make the ship journey to the UK. Hydrangeas, endemic to Asia and America, made a similar journey to Europe at the height of colonialism.

Of course, the movement of plants around the world is as old as global trade, and global trade predates European colonialism by many centuries. But the rules of engagement seem to have changed dramatically during colonial times. One of the ways this manifested was in how Europeans, including the English, looked at the natural world in their colonies across Asia, Africa, Australia and South America; how they sought to categorize, label, control and even own specimens in ways that have outlasted the Empire; and how extractivist policies allowed for the removal of rare plants as well as the setting up of large single-species plantations in what were previously biodiversity hubs.

These projects – of extracting and shipping species as well as documenting them at location – of course needed feet on the ground. These could be Europeans, or they could be drawn from the local population, but often, they were a mix of both.

A section of ‘A Treasury of Life: Indian Company Paintings c. 1790-1835’ is devoted to drawings documenting and categorizing plants of local significance by Europeans as well as Indian artists. Case in point: artworks by James Forbes, an East India Company official whose work took him to multiple places in India, from Mumbai to Kerala.

In a catalogue-cum-essays book accompanying the show at DAG, Aditi Mazumdar writes that James Forbes created around “52,000 pages…of first-hand sketches and notes on India’s flora, fauna, culture, customs, traditions of local people” during his time in India between 1749 and 1819. His depictions of the “Sahras” or Sarus crane in Gujarat, the “Spotted Kingfisher, and a Singular Frog on the coast of Malabar” and the “Bulbul or Indian Nightingale, on a sprig of the Custard Apple Tree” were part of the larger colonial knowledge gathering enterprise. In her essay, “Art, Nature & Empire”, Mazumdar adds: “Regardless of the inaccuracies, his (Forbes’s) detailed illustrations and personal observations clearly show that Forbes’s efforts were intended to contribute to natural historical-knowledge making.”

Though Forbes had minimal training in draftsmanship – which he received as an employee of the EIC – his extensive drawings were in line with the scientific style preferred in Europe at the time and his work became influential. The breadth of his travels also gave him the opportunity to observe plants and animals in multiple Indian locations.

Giles Tillotson, senior vice-president of exhibitions at DAG (formerly Delhi Art Gallery).Local artists, foreign patrons

Giles Tillotson, senior vice-president of exhibitions at DAG (formerly Delhi Art Gallery).Local artists, foreign patronsAround the same time, Indian artists from Murshidabad to Tiruchirappalli had started taking commissions from English patrons, to make watercolours and gouaches depicting Indian plants, animals, and customs, among other things.

"Towards the end of the eighteenth century it became fashionable among Europeans living in India to commission or collect watercolour paintings by local artists," historian Rosie Llewellyn-Jones wrote in an essay on the 'Louisa Parlby Album', for Francesca Galloway, in 2017.

The paintings on show at DAG currently come from this same collection made by Louisa Parlby. Parlby was an Englishwoman who came to India around 1795. Married to an engineer in the employ of the East India Company, James Templer Parlby, she lived in Maidapur, near the Berhampore Cantonment in Bengal, till 1801 or 1803.

"These watercolours," Llewellyn-Jones added, "were not designed to be hung on the walls of European houses in India, but were carefully mounted into albums or stored in portfolios which were kept in libraries or drawing rooms and shown to favoured friends... Indian watercolours were within the reach of moderately prosperous East India Company officers and their ladies. The paintings were skilfully executed... An album could accompany its owner if he was ordered to a different part of India, as officers frequently were. If he or his lady lived long enough to return home to Britain, the album went with them too, to be shown off as a rather splendid souvenir."

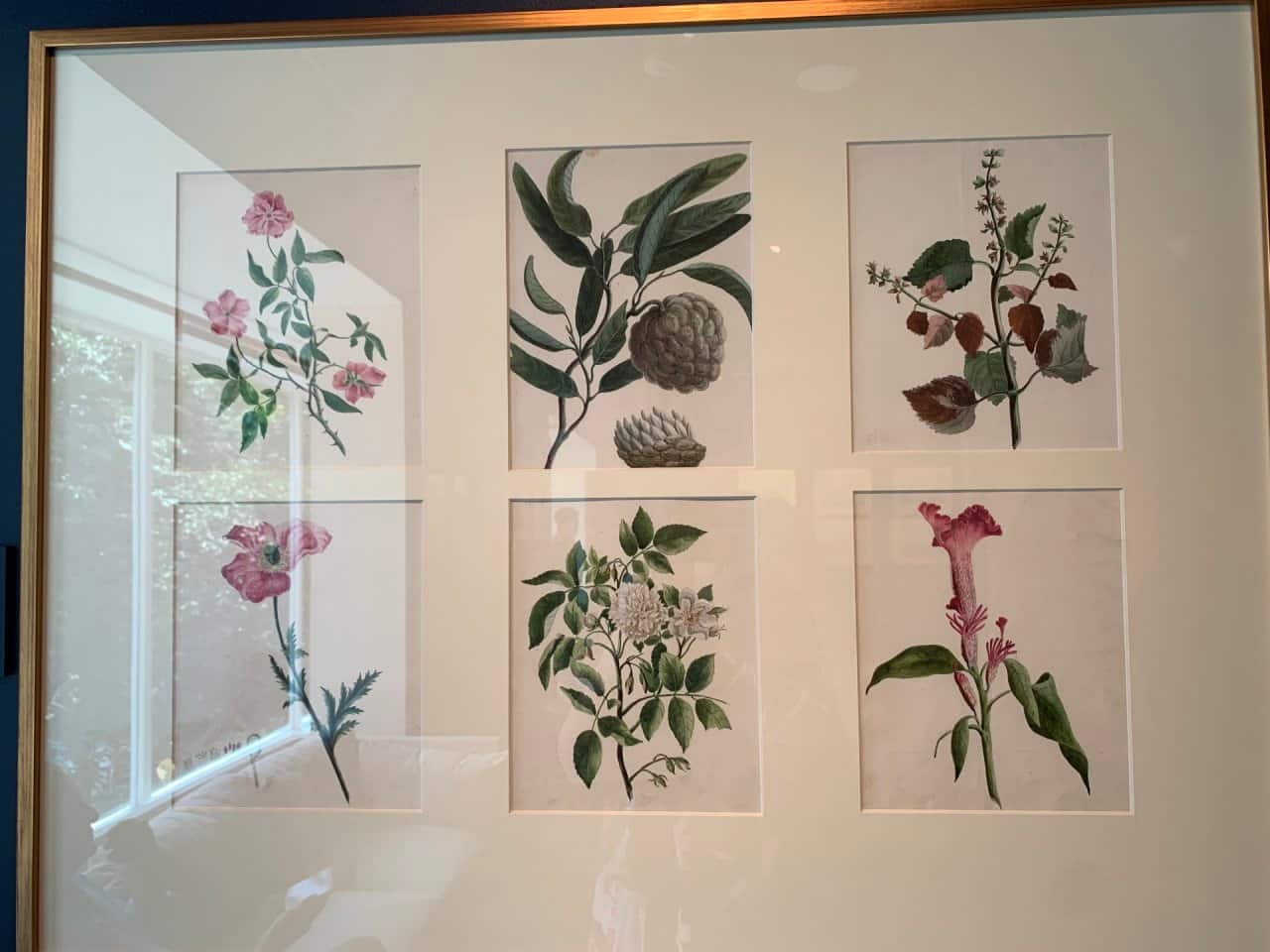

Louisa Parlby's Album contains more than 84 folios, including watercolours depicting the palatial homes of the European residents of Maidapur and natural history paintings depicting plants like poppies, banana flowers, tobacco, Indian orchid or kachnar, pomegranates, datura, melons, among others.

While botanists like Hendrik Adriaan van Rheed who studied flora in the Western Ghats in the late 1600s and William Roxburgh at the Calcutta Botanic Garden who famously sent botanical illustrations of Indian plants to Kew Garden in London, had been contributing to an official colonial knowledge-gathering mission - to better understand the colonies - Louisa Parlby's interest in commissioning the works seems to have been personal. "It operates on different levels. But if you are an 18th century European who finds yourself in India because your husband works for the East India Company, you are surrounded by things you've never seen before. And that's what sparks an interest... It still reflects a kind of colonial engagement with the world," Tillotson says.

From the Louisa Parlby Album, folios depicting plants grown in gardens in and around Murshidabad, Bengal. These plants may have been new and exotic to Parlby, but they would have been familiar to the Indian artists commissioned to paint them in the style of European botanical illustrations.Indian skill, European science

From the Louisa Parlby Album, folios depicting plants grown in gardens in and around Murshidabad, Bengal. These plants may have been new and exotic to Parlby, but they would have been familiar to the Indian artists commissioned to paint them in the style of European botanical illustrations.Indian skill, European scienceIndian painters of the folios in Louisa Parlby's Album would have painted local flora before, but in a very different context. In an essay in the catalogue-cum-essays book accompanying the DAG show, art historian and botanist Nicolas Roth who is associated with the Harvard University, writes: “At least for the works included here, all of these artists working in a variety of materials and in different locations across the Indian subcontinent and beyond turned to the same set of plants deeply implicated in human material, aesthetic and spiritual pursuits. These are familiar plants, domestic and domesticated, which helped constitute the local life worlds and systems of meaning, even as European patrons may have seen them mainly as exotica to be collected.”

Roth goes on to cite examples. Like how poppies and nargis flowers were often used as stand-ins for passion and vision/clarity, respectively, in Mughal-era art and poetry. The artists commissioned by Parlby would most likely have painted these specimens before, but they would have painted them in their larger context – in a Mughal court or garden – rather than as the central focus of the piece. Medicinal plants and plants with spiritual significance to the artists, like tulsi and datura, too occur in among Parlby’s folios. The plants themselves meant something to the artists, though it’s unclear who chose the works depicted in the Louisa Parlby Albums – she, the artists, or a third party, or some composite of these. But like Roth writes, “Far from the general inventory of wild native vegetation of Bengal or of any other region of the Indian subcontinent, they (the selection of plants in the album) represent a sort of highlight reel of contemporary garden flora.”

Additionally, Roth writes, if the European scientific-drawing style of the time required that artists compress time like an accordion to depict a plant in various stages of flowering and fruiting at once, the Indian aesthetic too peaked through - sometimes in rococo-like tendrils delicately balancing the work visually.

Author William Dalrymple, whose book ‘Forgotten Masters: Indian Painting for the East India Company’ accompanied an exhibition he curated for The Wallace Collection, London, in 2019-20, explained in a talk at DAG earlier this month that the Indian artists creating these works would most likely have seen journals where the natural world was depicted in the style favoured by the European scientists of the day.

Dalrymple explained that some other Europeans serving in India at the time – like the French Major-General Claude Martin who arrived in India around 1757, and after whom Lucknow’s La Martiniere College is named – were importing scientific journals and ideas around how to depict natural history specimens, too. And the local artists painting these pictures for the Europeans might have come by them either through their patrons – who were anyway procuring European paper and paints for them – or heard of them through their own networks among artists.

'A Treasury of Life: Indian Company Paintings c.1790-1835', edited by Giles Tillotson. (Image: DAG)Local experts and knowledge

'A Treasury of Life: Indian Company Paintings c.1790-1835', edited by Giles Tillotson. (Image: DAG)Local experts and knowledgeCompany painting refers to art made by Indian artists for foreigners, mostly Company patrons, in the 1700s and 1800s. Dalrymple, among other historians of that period, have in the past objected to the way this categorization privileges the buyers of this art over the creators.

It's not a unique obliteration of local experts and creators, either. The Louisa Parly Album is partly known as such because she signed only her own name at the back of the paintings, with no notes about the procurers and painters of the plants depicted in her “album”. It’s not quite clear whether she commissioned multiple artists to create the works piecemeal or hired a few artists for longer periods.

During this period, Europeans like William Roxburgh at the Calcutta Botanic Gardens (now called Acharya Jagadish Chandra Bose Indian Botanic Garden), Mary Impey and Claude Martin, too, were commissioning Indian artists to paint local flora in the style of European botanical illustrations. In the case of Louisa Parlby, the paintings were more for private consumption than scientific research. In that sense, perhaps, they speak to the kind of consumerist imperialist impulse that also drove the craze for the Cattleya orchid in the early 1800s.

To be sure, our urban gardens today bear the marks of globalization too. But this, as indicated before, is nothing new. Even the Louisa Parlby Album features China roses and tobacco - originally thought to have come from North America. Presumably these plants had been in India long enough by the late 1790s, to have gathered local significance and to make it into the selection that Parlby commissioned.

One final observation: Louisa Parlby wasn't the first or even the most important European collector of these natural history Company paintings. Others like Mary Impey, James Forbes, Claude Martin and William Roxburgh - onetime director of the Calcutta Botanic Garden - prepared folios that covered more ground. Late last year, Kew also published a brochure of such several drawings in need of sponsorship for conservation. Among these folios are works commissioned by Martin, a George Govan who paid artists Rs 40 out-of-pocket when the Bengal government of the day refused to fund his project, and Dr Francis Buchanan-Hamilton who was in-change of the Kolkata botanical garden in 1814-15. Nevertheless, Parlsby's set is significant as a kind of time capsule of how Europeans lived in colonial Bengal, and a reminder of British Raj-era Indian treasures that may still be tucked away in private collections in the UK, away from public view a century or more later.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.