It was a meeting of the worlds at the 78th Festival de Cannes, where Satyajit Ray fanboy Wes Anderson, alongside Ray’s actresses Sharmila Tagore and Simi Garewal, introduced the restored version of Ray’s 1970 film Aranyer Din Ratri (Days and Nights in the Forest) at this year’s Cannes Classics screening. The American filmmaker participated in and supported its 4K restoration, from the original camera negative and sound preserved by film’s producer Purnima Dutta, by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project at L’Immagine Ritrovata, together with Shivendra Singh Dungarpur’s Film Heritage Foundation, Janus Films and Criterion Collection.

Fanboy of Ray’s “novel-like” cinema, Anderson dedicated his 2007 comedy-drama, The Darjeeling Limited, to the maestro and used music from Ray’s films for it. The “memory game” scene in Anderson’s Asteroid City (2023) was a direct hat-tip to the iconic memory game sequence in Aranyer Din Ratri. Anderson, by his own admission, had “stolen” it. Speaking about having met him in Cannes, Tagore says, “Wes Anderson was so well informed about Manik da (Satyajit Ray), he’d seen his films and told us that the first film he saw of Manik da’s was Teen Kanya (1961), which he found in a flea market in the US, in an old video store. He was completely overwhelmed with the films. Since then, he’s been an admirer. The memory game in Asteroid City is a little different (from Aranyer Din Ratri) because they are saying all the names of famous people, but because they are so clever and there is no contest, so they start saying it in the reverse order. So, that’s the challenge. Wes has a nine-year-old daughter and he said, as a family also they play this game.”

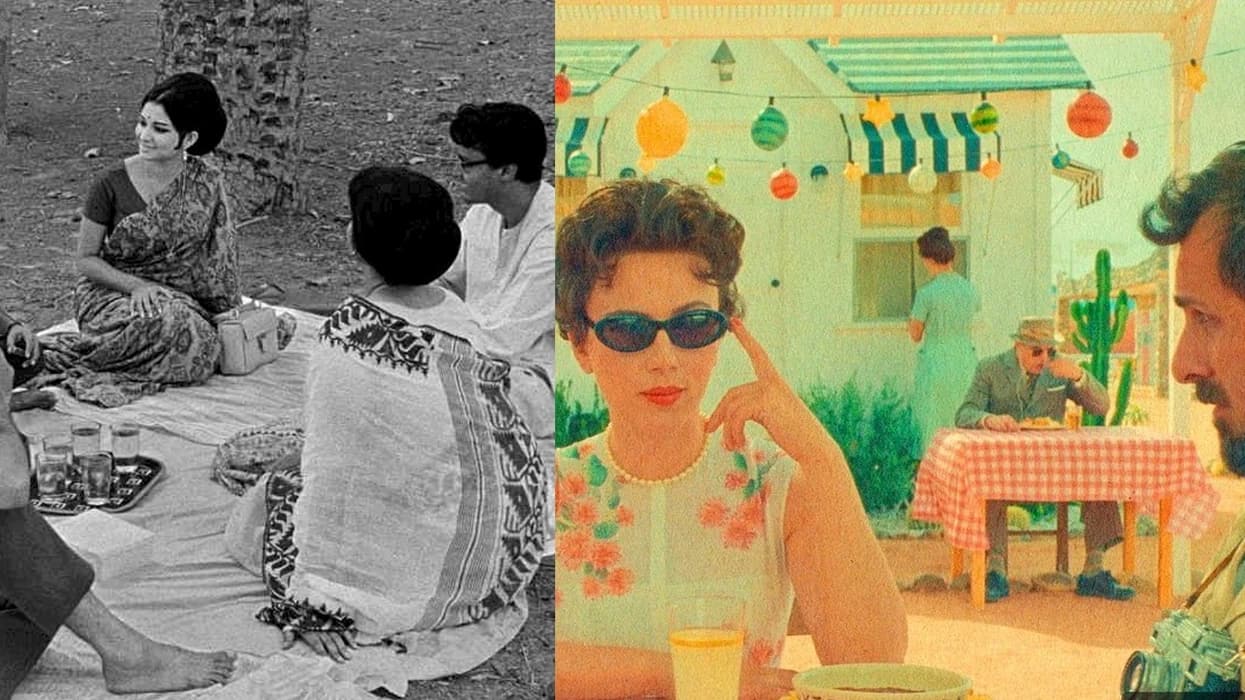

(Right) The memory game in Wes Anderson's Asteroid City (2023) was inspired from the memory game in Satyajit Ray's Aranyer Din Ratri (1970).

(Right) The memory game in Wes Anderson's Asteroid City (2023) was inspired from the memory game in Satyajit Ray's Aranyer Din Ratri (1970).In Soumitra Chatterjee and his World (2025, Penguin Random House), Sanghamitra Chakraborty writes, “The famous memory game scene in the film comes a little ahead of the climax. It is a witty and compelling study of the characters, their proclivities, their ability to stay the course and the various interpersonal dynamics.” The camera was placed in the middle and the actors were seated on the ground around it. Ray sat in the middle looking through the camera and took a 360-degree pan as the game progressed. Through his close-ups, with the roving camera paused on each face, Ray superbly captured their mental landscape and the emerging group dynamics.”

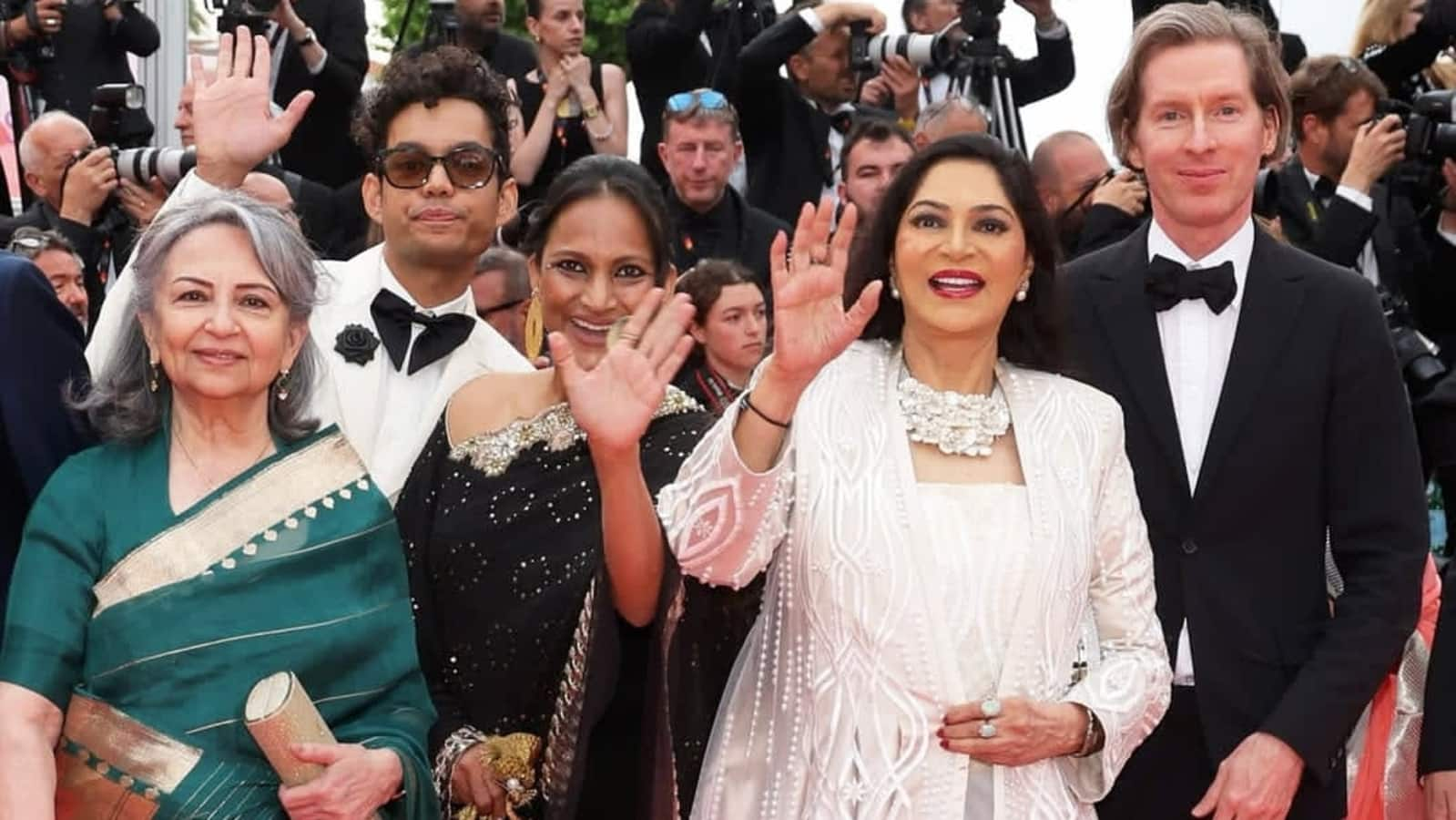

Actors Sharmila Tagore (in green) and Simi Garewal (in white) with filmmaker Wes Anderson on the red carpet at the 78th Cannes Film Festival. (Photo via X)

Actors Sharmila Tagore (in green) and Simi Garewal (in white) with filmmaker Wes Anderson on the red carpet at the 78th Cannes Film Festival. (Photo via X)Anderson, excited to meet Ray’s actors in person, had umpteen questions that Tagore fielded. She recalls how “extremely fond of India and Satyajit Ray” he was and how “well informed” he was. “It’s one thing to like somebody and another thing to know about their work. Anderson asked me how was Manik da, how did he direct me, how was Soumitra as a person...and I didn’t know so much about him so that I could ask him questions. I really regret that. I should have learnt a little bit about him before I met him because he’s such a wonderful person and so well respected and admired.”

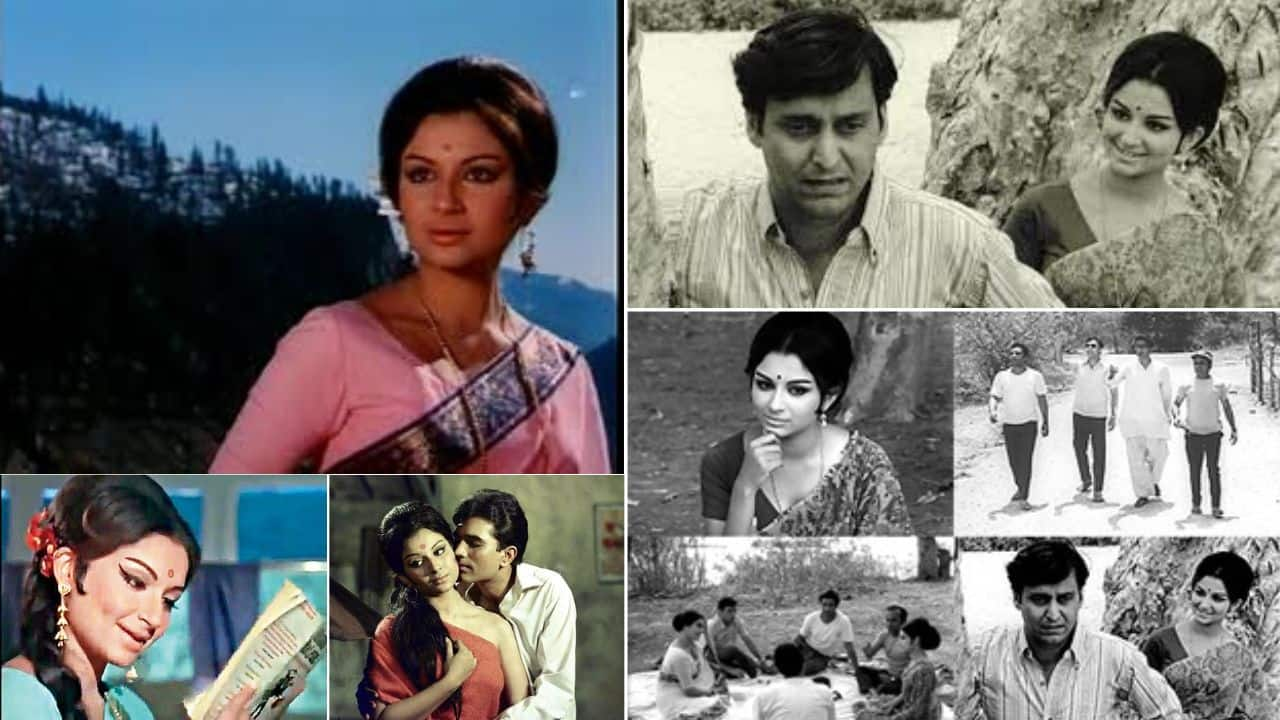

Ray, who gave Tagore her film debut at age 13 with Apur Sansar (1959), the final film of his Apu Trilogy, would go on to direct her in four more films: Devi (1960), Nayak (1966), Aranyer Din Ratri (1970) and Seemabaddha (1971). The cherubic Aparna of Apur Sansar becomes world-weary Aparna Tripathi in Aranyer Din Ratri. And Aparna Chatterjee of Goutam Ghose’s Abar Aranye (2003) — a sequel to the Ray film — walked away with the National Film Award for Best Actress in a Supporting Role. Her second National Award after her Best Actress in a Leading Role award for the Gulzar-directed Mausam (1975). For Aranyer Din Ratri, when Ray approached Tagore, then a leading Bollywood star, she was already shooting for Shakti Samanta’s Rajesh Khanna-starrer Aradhana (1969), and somehow managed to shoot for both the films simultaneously.

Sharmila Tagore shot for both Aradhana (1969) and Aranyer Din Ratri (1970) simultaneously.

Sharmila Tagore shot for both Aradhana (1969) and Aranyer Din Ratri (1970) simultaneously.If Aranyer Din Ratri’s Aparna Tripathi is on the top of her game — in the memory game — the loss of memory of her character Mrs Sen brought her back to Bengali cinema after 15 years in Suman Ghosh’s Puratawn, which released in theatres this year and closed the Habitat Film Festival in Delhi last month. In it, she plays an ageing mother who lives away from her city-dwelling daughter and is losing herself to Alzheimer’s disease. In Aranyer…, she’s a cerebral city-bred woman in the forest of Palamau who becomes Ray’s moral compass in this film, and in all their outings together, to show hollow men and critique male entitlement, arrogance, pomposity, intellectual elitism, shallowness, and middle-class hypocrisy.

Sharmila Tagore in a still from 'Puratawn' (2025).

Sharmila Tagore in a still from 'Puratawn' (2025).“In Aranyer Din Ratri, Ray uses the recognisable plot device of ‘fish out of water’, taking the characters out of their familiar city surroundings and plunging them into an unfamiliar territory. Here, they introspect and encounter aspects of themselves and their companions that are revealed to them through slightly unreal situations,” writes Chakraborty in her book, “Days and Nights in the Forest is a prelude to Ray’s City trilogy, each a saga of disillusionment. Though it unfolds in the serene forestlands, it is very much urban.”

In this oft-seen-as a coming-of-age story, the four young men (Asim, Sanjay, Shekhar and Hari) “are from Calcutta, unsettled by political turmoil, joblessness and by the general despondency of the Naxal era. Soumitra plays Asim, a once-idealistic young man who has started climbing the corporate ladder. He appears supremely confident and casually condescending,” Chakraborty writes, “Aparna Tripathi seems deliberately built with a superior air, almost as a fitting contrast to the male characters.” Here, too, “Ray’s gaze at masculinity is unforgiving. Ray’s women in Days and Nights... are creatures of superior moral sensibility and his men all helpless children”…“It is hard to not see the master and his protégé, Ray and Soumitra, as the feminist allies of that era,” she writes.

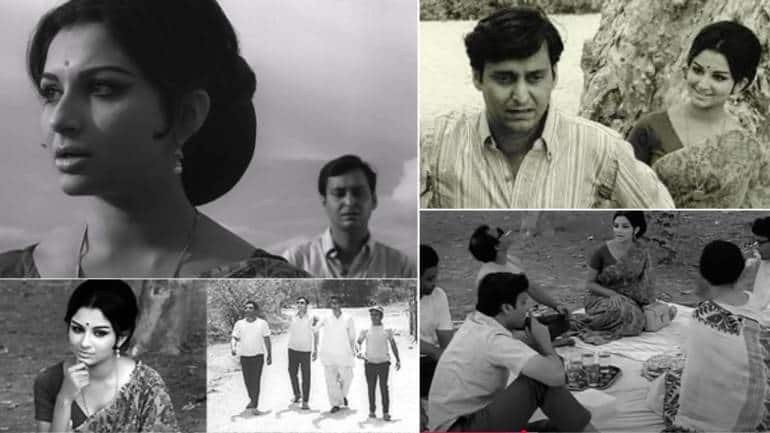

Stills from Aranyer Din Ratri (1970).

Stills from Aranyer Din Ratri (1970).“The first half has the appearance of light comedy but there’s a steady modulation to a serious key,” wrote Satyajit Ray in Deep Focus: Reflections on Cinema (2011; edited by Sandip Ray; HarperCollins). Acknowledging his debt to Western Classical music, in particular to the influence of Mozart’s “operas and his miraculous ability to have groups of characters maintain their individuality through elaborate ensembles,” Ray writes, “Leporello’s stuttering fright, the don’s bravado in the face of doom and the Commendatore’s relentless intoning of his challenge in the Statue scene in Don Giovanni [Mozart’s opera in two acts] is one example. I am greatly fascinated by the possibility of such ensembles in films. The memory game in Aranyer Din Ratri attempts this. Here the game itself is the ground bass over which the six characters play out their individual roles in word, look, and gesture.”

“The film says a lot,” Ray wrote, “but not always in words, certainly not in those of rhetoric. What is attempted in these films and in most other films of mine is, of course, a synthesis.”

The memory game sequence in Palamau forest in Aranyer Din Ratri.

The memory game sequence in Palamau forest in Aranyer Din Ratri.In an interview with Moneycontrol, Sharmila Tagore talks about being instrumental in essaying Ray’s idea of a strong woman, her equation with her two Bengali co-stars Soumitra Chatterjee and matinee idol Uttam Kumar, and balancing Bengali cinema with Bollywood. Excerpts:

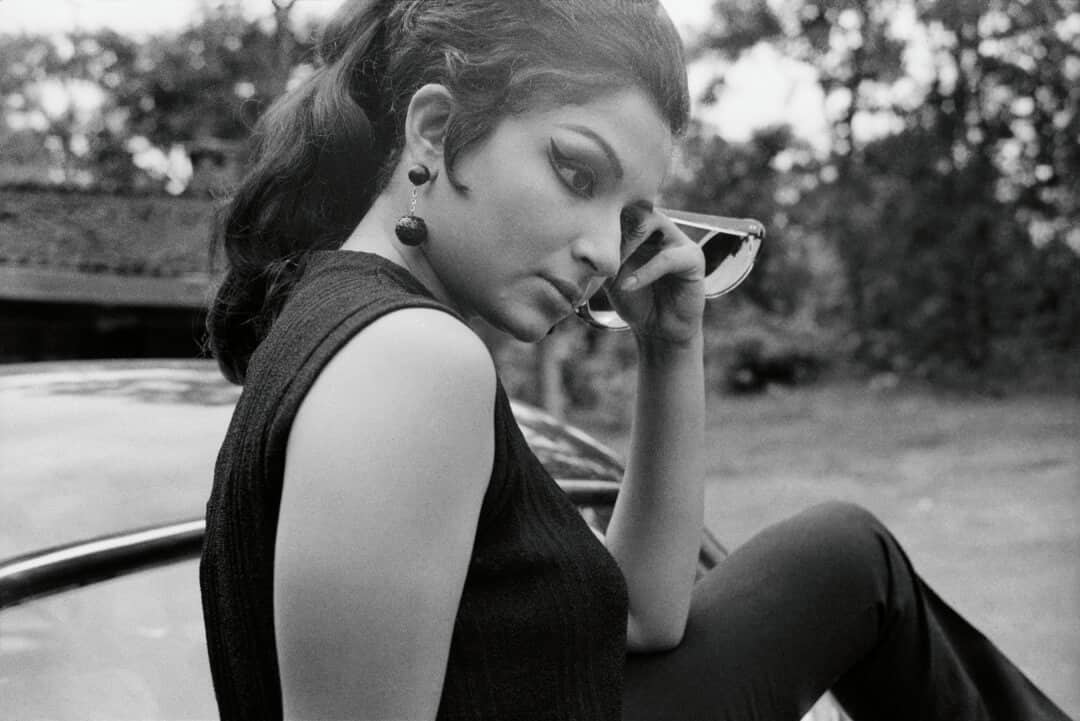

Sharmila Tagore between the scenes of Aranyer Din Ratri in 1969. (Photo by Nemai Ghosh/via X)Aranyer Din Ratri is a very complex, layered film. As someone who has been directed by Satyajit Ray, from your perspective, how do you interpret that film as compared to, say, Nayak? In both the films, a certain male vanity is peeled away.

Sharmila Tagore between the scenes of Aranyer Din Ratri in 1969. (Photo by Nemai Ghosh/via X)Aranyer Din Ratri is a very complex, layered film. As someone who has been directed by Satyajit Ray, from your perspective, how do you interpret that film as compared to, say, Nayak? In both the films, a certain male vanity is peeled away. Not comparing. It’s (Aranyer Din Ratri) a story about four educated men who come to the forests of Palamau for a vacation and they come to the forest to get that kind of experience away from the city life. And Manik da wants to say somewhere that if people like this who cannot experience the sunset or the forest naturally without the trope of American films or Tarzan, how can they be culturally superior? And they are very superior and have a very, very masculine way of looking at things, they are full of themselves. And I mean, they give this bribe to the chowkidar who’s not allowed to let anybody stay there without proper permission. And they bribe him. And then later they say thank God for corruption, meaning the chowkidar is corrupt, but they are not corrupt in offering bribe. So that’s the way they see and look at life. So, the learning when they, when they leave…the ending is very wonderful because when they leave the forest, all of them are slightly altered. Not all of them, three of them. Shekhar remains the same, which has been brilliantly played by Rabi Ghosh, he remains the same. And the agent of this change are these two women who through just being there, they make them the men, and, of course, Simi and Samit Bhanja. There also he learns the consequences of his action. So, all these men are slightly altered and better when they go back.

Stills from Nayak (1966).And that as compared to Nayak?

Stills from Nayak (1966).And that as compared to Nayak?Nayak is different. It’s an exploitation of a person’s being. When we see a star, we think of him as someone we see on the screen, we don’t know the real person. We read gossip magazine and we judge them. We form our own opinion, which are not necessarily true because behind all that, he’s a human being just like us. So, how through conversation, the whole story unfolds and the journalist who had been little patronising towards him understands that he’s also struggled. He is a human being after all. So that is wonderful. And also, the structure of the story, the different compartments are sort of different lives and how they unfold and Manik da sets up these stories, but there is no conclusion. We don’t know what happens to them. We just get a glimpse of them. And then they also are a part of… and the end is again lovely because the moment the star gets down from the compartment, he’s surrounded by his admirers and fans. Whereas when I get out of the compartment, my uncle is waiting for me and we just walk away. So, he’s kind of hemmed in where he is and there’s more freedom for us. We can because we are unknown people. So, nobody’s looking at them while he is scrutinised and admired and hemmed in.

Sharmila Tagore in Satyajit Ray's films (clockwise from top, left) Apur Sansar (1959), Devi (1960), Seemabaddha (1971), Nayak (1966), Aranyer Din Ratri (1970).In all of Ray’s films, you encountered a certain stereotype of Bengali men: the stuck-up film star, the lover boy, the yuppie, the confused manly men and the traditionalist. Meanwhile you stayed the same, the slightly sceptical, questioning, holding a mirror to the male, but in a subtle manner you transform from being innocent to world-weary. Do you see yourself as a continuum of the many avatars of 20th century Bengali women in Ray’s imagination, handling the men in her life with a certain sangfroid and a studied indifference?

Sharmila Tagore in Satyajit Ray's films (clockwise from top, left) Apur Sansar (1959), Devi (1960), Seemabaddha (1971), Nayak (1966), Aranyer Din Ratri (1970).In all of Ray’s films, you encountered a certain stereotype of Bengali men: the stuck-up film star, the lover boy, the yuppie, the confused manly men and the traditionalist. Meanwhile you stayed the same, the slightly sceptical, questioning, holding a mirror to the male, but in a subtle manner you transform from being innocent to world-weary. Do you see yourself as a continuum of the many avatars of 20th century Bengali women in Ray’s imagination, handling the men in her life with a certain sangfroid and a studied indifference?It’s a good question. What Ray feels and the critics also felt that the women are more morally superior than men in films like Aranyer Din Ratri and Seemabaddha. Even in Mahanagar (1963), the girl’s character is very strong. So, yeah, Manik da portrayed characters like that, like Sarbajaya (Karuna Banerjee) in Pather Panchali (1955). So, there are many characters, in Mahanagar and even in Charulata (1964). So, the women play a very, very strong role and Manik da respected women. He was raised by women, a single mother/widowed mother, and wife. And Monku di (Ray's wife Bijoya Ray) had many cousins, women cousins. I always saw him playing Scrabble or something with them. So, I think his innate respect for women most certainly was there, and in the film, he over and over again showed the strength of women. Like in Pather Panchali, in the Apu Trilogy, the mother’s role is so strong. She’s so, so self-contained and deals with all kinds of issues so well, with so much fortitude and dignity. That’s the way Manik da saw the world and saw women and saw the family structure. Even Ghare Baire, Bimala’s husband gave her so much independence, but he dies. She was distracted for a little while. But without that, she was relegated to the background as a widow. Widows had no rights. Whereas he allowed her to go out of andarmahal to the baithak and she didn’t quite appreciate it. In Devi, of course, she is a victim of the system. And my part in Apur Sansar is very, very sweet and very romantic. And, again, her strength, how she copes in a nuclear family, cooking and sewing, putting new curtains and all that which she hadn’t done before at a very early age. So, she is very strong. In Seemabaddha, she’s the conscience. In Aranyer Din Ratri, without saying anything, he shows Asim that if you know everything, you don't have to flaunt it and real confidence comes from knowing who you are, not just impressing other people. So, yes, I’ve had the good fortune of working in women’s roles which are very strong.

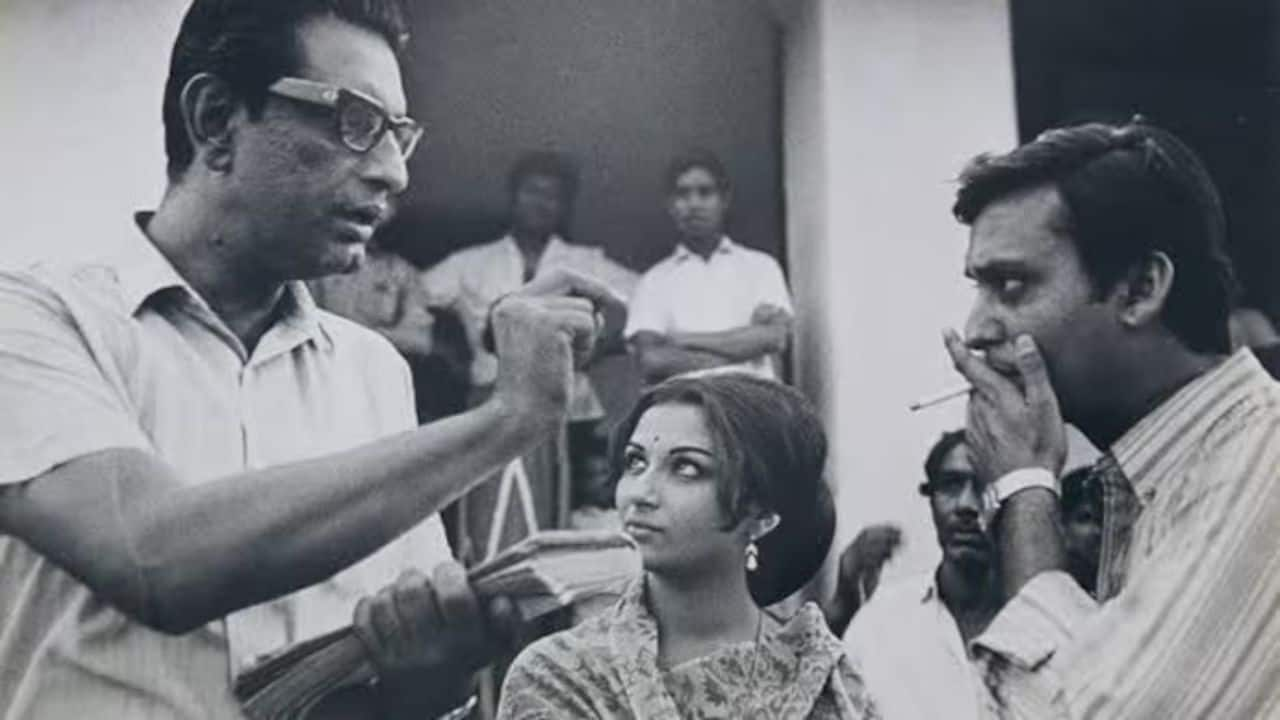

Satyajit Ray (left) directing Sharmila Tagore and Soumitra Chatterjee during Aranyer Din Ratri. (Photo via X)How did you balance Shakti Samanta or mainstream Hindi cinema and Satyajit Ray or Bengali arthouse cinema?

Satyajit Ray (left) directing Sharmila Tagore and Soumitra Chatterjee during Aranyer Din Ratri. (Photo via X)How did you balance Shakti Samanta or mainstream Hindi cinema and Satyajit Ray or Bengali arthouse cinema?When the camera comes on, we are all performing. We as actors, wherever we go, we try and do our best according to the script, according to what the director wants us and we put our own effort in it. So, I wouldn’t want to judge Shakti ji. We are performers, we can step into this role and that role and that’s our job, so, we do it to the best of our abilities.

Sharmila Tagore and Uttam Kumar in a song sequence from Sesh Anka (1963).

Sharmila Tagore and Uttam Kumar in a song sequence from Sesh Anka (1963).Next year is Uttam Kumar’s birth centenary. How was he as a co-star and in contrast to Soumitra Chatterjee?

Uttam was a wonderful co-star. My first Bengali film was with him. I mean Bengali when I came back, Sesh Anka (1963, directed by Haridas Bhattacharya) and he was brilliant and very supporting. The films that I’ve worked with him, I’ve been very happy with him and he’s been very considerate and helpful and, of course, a wonderful star. He was the heartthrob of Bengal. He could fit in as a brother’s role, lovers’ role, any kind of role. As a contrast [to Soumitra], both were actors, both were different kinds of actors and both were very popular. Uttam had that kind of star quality. I mean you would imagine him going in a car and a chauffeur opening the door, but you could imagine Soumitra going in a bus or a cycle or anything. He was more a people’s man because when he passed away, the funeral was endless. I mean the procession was endless and with flowers and every balcony was full. Kolkata really gave him a wonderful farewell. So, they adored him as somebody of their own and very close to him. Whereas Uttam was a star and somebody to be admired from far, they couldn’t get close enough for him. I was closer to Soumitra, naturally, because I worked with him in my first film and we were very good friends.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.