The last wholesome place on the Internet: that’s how BookTok, the corner of TikTok devoted to books, has been described. Highly recommended titles include Colleen Hoover’s It Ends with Us, Taylor Jenkins Reid’s The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo and Sarah J. Maas’s A Court of Thorns and Roses. Fantasy, romance, and period adventures seem to be the main picks.

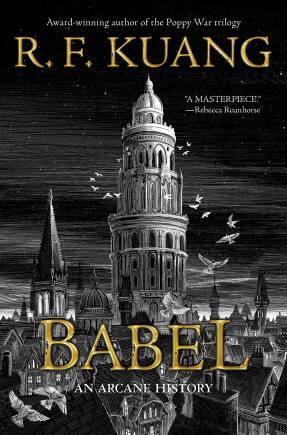

Among the recent videos that have racked up millions of views are those in praise of R.F. Kuang’s Babel. A novel about a group of young scholars in 19th century Oxford, involving critiques of colonialism and translation? Sounds irresistible.

Among the recent videos that have racked up millions of views are those in praise of R.F. Kuang’s Babel. A novel about a group of young scholars in 19th century Oxford, involving critiques of colonialism and translation? Sounds irresistible.

Kuang’s earlier The Poppy War, the first of a trilogy and a finalist for the Nebula, Locus, and World Fantasy Awards, was inspired by the Opium Wars. Babel, another fantasy epic with the same unsavoury episode at its core, has a wider ambit.

The novel starts in 1829 with the plight of an orphaned dock boy in Canton, which is in the grip of a cholera outbreak. Because of his ability to speak English and Cantonese, he is taken under the wing of a professor who foresees a future for him in Oxford’s Royal Institute of Translation, also known as Babel. The boy calls himself Robin Swift, a surname chosen after the author of Gulliver’s Travels, another book about a stranger in a strange land.

After a stint in London brushing up his knowledge of English and learning Greek and Latin to boot, Robin enters the institute where he befriends other fish out of water. Chief among them is Ramy, or Ramiz Rafi Mirza, the scion of a once-wealthy family from Bengal.

Ramy’s formerly well-off parents had to give up their landholdings because of Cornwallis’s Permanent Settlement, and work for the secretary of Calcutta’s Asiatic Society. Now in the heart of the empire, he says: “The English are never going to think I’m posh, but if I fit into their fantasy, then they’ll at least think I’m royalty.”

The others in the circle are the principled Victoire, from France, and the prim Letitia, daughter of an English admiral. They form a bond and become “the colours of Robin’s life”. Episodes of unashamed racism and sexism draw them even closer.

In this way, the immediate reference points for Babel are Donna Tartt’s The Secret History and Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy. However, Kuang’s creation has plenty of inventiveness and ingenuity of its own. It is also more grim and dark.

The students start their coursework at the Oxford tower that contains “the only comprehensive, authoritative collections of knowledge of every language that exists”. The institute is devoted to translation because this art, along with the properties of silver, keeps Britain at the centre of the world. As one character puts it: “Ask yourself why the Literature Department only translates works into English and not the other way around.”

In this alternative universe, silver and not spice is the reason for colonial trade, with British ships bringing back vast quantities from all over. It hums through England, Kuang writes, glimmering from the wheels of carriages and horses’ hooves, shining from windows and doorways, glowing from under the streets and in the ticking arms of clock towers.

When fashioned into bars inscribed with pairs of translated words, silver magically amplifies physical properties. Machines work faster, ships speed up, and weapons become deadlier: it is the very backbone of the British Empire. With the matched pairs devised in Babel, silver becomes the ideal vehicle to capture what gets lost in translation and then manifest it into being.

Such world-building neatly repackages historical realities. The Industrial Revolution becomes the silver industrial revolution; Luddites and others go on strike because of its effects; and opening up China to the opium trade is vital because of the money needed to acquire more of the precious metal.

As Robin and his cohorts are drawn deeper into the workings of Babel, the extractive nature of the enterprise becomes more and more clear. After being contacted by a secret society, they become unsure of whom to trust, leading to plots with fatal consequences. A radicalised Robin starts to walk down a path later outlined by Franz Fanon: colonialism’s “naked violence” only gives in when confronted with greater violence.

Much of this is engrossing, but an over-reliance on exposition makes Babel lose some of its power. The insidious nature of colonialism and the way it co-opts minds and materials for its own ends are spelt out time and again, including in several footnotes. Kuang’s premise is inarguable, and seems to be driven by a seething desire to set the record straight - but one wishes that the delivery was less polemical and more novelistic.

With its etymological references, on-the-nose broadsides against imperialism, and incidents of brutality, Babel may seem like an unusual candidate for popularity on BookTok. However, Kuang knits these elements into a vivid saga set in an alternative historical past. It’s not only immersive in its own right, but can serve as a stepping stone to further reading on the smug, self-serving and savage mentality of the colonial enterprise.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.