On August 20, 1931, Mahatma Gandhi wrote a letter to one Maulvi Mohammad Ali in Dharavi, Bombay, saying, (I have) “been attending to your matter. I have not yet attained any success.” This is just one of the thousands of letters in Gandhi’s copious correspondence, which runs into 98 volumes.

Scholars and students of South Asian history are aware of the Khilafat Movement and its key leaders, the brothers Maulana Mohammad Ali and Maulana Shaukat Ali, who made Bombay (now Mumbai) their base. So the former would come across as the most likely candidate to be the recipient of Gandhi’s letter.

But Maulana Mohammad Ali died in January 1931 (and relations had soured between the brothers and the Mahatma by that time), so the letter could not be addressed to him. So, who was this Maulvi Mohammad Ali who was residing in Dharavi, and what was the matter in which Gandhi had taken an interest?

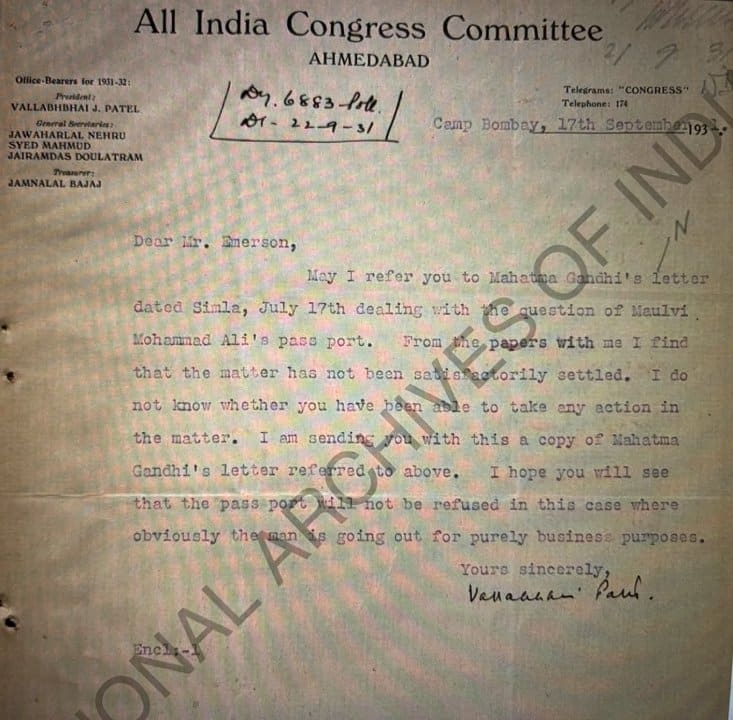

(Photo credit: National Archives of India)

(Photo credit: National Archives of India)

Piecing together information from the archives in London, Mumbai and Delhi, it appears Maulvi Mohammad Ali was the uncle of Khurshid Mahmud Kasuri, the former foreign minister of Pakistan.

Popularly referred to as Maulvi Mohammad Ali ‘Dharavi’, as he was a wealthy and prominent merchant with workshops and offices in Dharavi, he was also a mathematics wrangler from University of Cambridge.

Unlike today, the appellation of Maulvi in those days did not necessarily denote a religious leader, but someone who was educated and influential. Maulvi Mohammad Ali’s father was Maulana Abdul Qadir Kasuri, who was a lawyer, and President of the Indian National Congress in Punjab. The family came from Kasur, a town near Lahore and hence the surname Kasuri.

The family belonged to the Ahl-i-hadith sect, were pan-Islamists and moved across the sub-continent. Maulvi Mohammad Ali went to Afghanistan in 1915 after his studies in Cambridge and worked at the court of Amir Habibullah, the ruler of Afghanistan. He was also appointed a minister in the “provisional government” of India led by Raja Mahendra Pratap in Kabul.

Indian revolutionaries wanted to enlist the support of the Afghan ruler to overthrow the British rule in India, but it was not to be. Maulvi Mohammad Ali was pardoned by the Punjab government in 1917 for this anti-British activity following which he settled down in Bombay as a leather merchant.

Dharavi today. (Photo by Adityan Ashokan via Unsplah)

Dharavi today. (Photo by Adityan Ashokan via Unsplah)

Dharavi, which is known for its hundreds of small-scale industries, developed as a convenient site for workshops and factories in the late 19th century away from the crowded and pricey real estate in colonial Bombay. One of the earliest and most famous tanneries in Dharavi was the Western India Army Boot and Equipment Factory established by the Bohra merchant prince Sir Adamjee Peerbhoy in 1887.

Supporting the freedom struggle

But moving to Dharavi was not the end of Maulvi Mohammad Ali’s anti-colonial activities. In Bombay, he aligned himself with the Congress party and was well-known to its top leaders.

In the wake of the embittered relationship between the Congress and the Muslims after the Khilafat movement, Maulvi Mohammad Ali Dharavi, along with other leaders like Bombay Chronicle editor S.A. Brelvi, Abdul Rehman Mitha and Yusuf Meherally, worked to mend fences.

In February 1920, when Maulana Azad visited Bombay from Delhi he stayed with Maulvi Mohammad Ali of Dharavi. He also used to trade with countries in Europe, England and USA and the Bombay police suspected him of providing funds to the Congress party as well. From 1922, the British suspected that he had renewed contacts with anti-British elements outside India.

In 1925, Maulvi Mohammad Ali applied for a passport saying that his export-import business necessitated a visit to United Kingdom, Italy, Germany, France and the USA. This was turned down by the government of Bombay.

In 1931, the Gandhi-Irwin pact (Lord Irwin was the Viceroy) secured the release of political prisoners, bringing about a somewhat relaxed atmosphere towards political activists. Records suggest that in 1931, Maulvi Mohammad Ali Dharavi again applied for a passport, suggesting that he needed to go to Europe primarily due to medical reasons and also use the opportunity for business dealings.

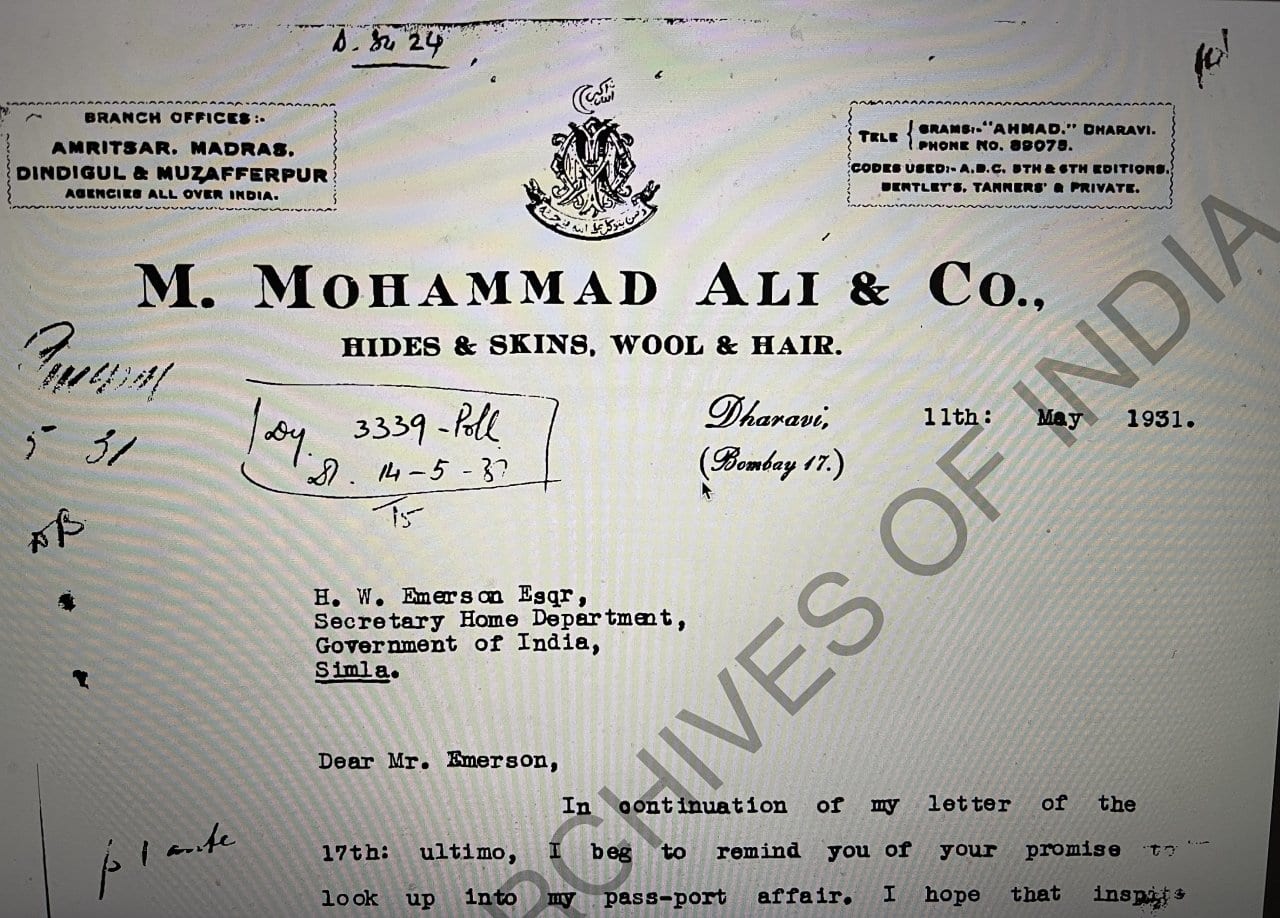

Mohammad Ali Dharavi's letter to the home secretary, reminding him of his request for a passport. In the 1930s, Indians involved in politics could only get an Indian passport if they wanted to travel for non-political reasons and if they had never been convicted for anti-colonial activities. (Photo credit: National Archives of India)

Mohammad Ali Dharavi's letter to the home secretary, reminding him of his request for a passport. In the 1930s, Indians involved in politics could only get an Indian passport if they wanted to travel for non-political reasons and if they had never been convicted for anti-colonial activities. (Photo credit: National Archives of India)

It seems that the government of India had declared that passports could be issued to those with past involvement in politics if they had no criminal conviction and the foreign journey was not related to political activities. There are no records to suggest that he was arrested by the Bombay police, although his younger brother Maulvi Mahmud Ali, the father of Khurshid Kasuri, was arrested, and underwent imprisonment, for taking part in a satyagraha.

Maulvi Mahmud Ali had attended schools in Pune and Panchgani and was a law graduate from University of Bombay. He later gained an MA in law from University of London and is regarded as the father of the human rights movement in Pakistan and was also the country’s law minister.

But even as Maulvi Mahmud Ali was a student of law, his brother was struggling to get a passport. When Maulvi Mohammad Ali formally wrote to the Bombay police commissioner seeking a passport in April 1931, it opened up a chain of correspondence on whether it would be prudent to issue him one. The matter generated plenty of letters and telegrams that flew between Bombay, Simla, Delhi, Mahabaleshwar, Ahmedabad, and Punjab.

Unknown to him, the Bombay government had continued to keep a tab on Maulvi Mohammad Ali. Intelligence files noted that he was a leading member of the Bombay Muslim Congress Party and that he continued to appeal Muslims to “join the non-violent war started by Gandhi” and that “British rule was sucking India’s blood.”

In his letters to the government of Bombay, Maulvi Mohammad Ali stated that being a merchant he was not an active political worker, although his sympathies and convictions had always been with the cause of Congress. At a meeting in Bombay in July 1929 he said: “(The) battle of rights between Hindus of the Mahasabha mentality and the reactionary Muslims had now reached the height of political instability.”

Maulvi Mohammad Ali had continued to attend and address meetings but did not openly conduct himself in a way that would get him arrested. That was perhaps because he had the responsibility to take care of his business. Political and business leaders started writing on his behalf pleading the administration to give him a passport.

On July 17, 1931, Gandhi wrote to H.M. Emerson, secretary, home department, government of India: “I understand that the passport has been refused because of his having participated in politics. But I have refused to believe that participation in politics could be used for refusing a passport for pure business purposes.”

The government of Bombay, however, maintained a hard stance on Mohammad Ali. An official of the home department in government of Bombay replied to Emerson that Maulvi Mohammad Ali was “actively disloyal” and that his “anti-British sentiments have undergone no change.”

Vallabhbhai Patel, too, followed up with Emerson, reminding him that the matter had not been satisfactorily settled. “I hope you will see that the passport will not be refused in this case where obviously the man is going for purely business purposes.” Patel wrote in his capacity as the President of the All India Congress Committee, and so did Sir Fazl-i-Hussain, a prominent politician from Punjab.

Maulvi Mohammad Ali also pleaded that it was his brother Mahmud Ali who had gone to jail and that newspapers routinely mistook one for the other.

Finally, Patel was informed by Emerson that the government of India could not interfere with the discretion of the local government in the matter. In this case, the government of Bombay was not inclined to issue passport to Maulvi Mohammad Ali of Dharavi.

Commerce department under British rule

Khurshid Mahmud Kasuri’s book Neither a hawk nor a dove does talk about his uncle, Maulvi Mohammad Ali’s sojourn in Afghanistan, but only vaguely mentions the family’s close association with Bombay. There is no mention of Dharavi, or of the fact that his uncle was a prominent leather merchant who moved around Bombay in a car.

Kasuri also gets it mixed up when he writes that “my father was arrested at the age of nineteen, as Secretary of the Bombay Congress during the ‘Quit India Movement’.” As per records, Maulvi Mahmud Ali was born in 1910, so he would be over 30 years old when the Quit India movement began in 1942. Thus Maulvi Mohammad Ali Dharavi’s letter to Vallabhbhai Patel in October 1931 in which he mentions that his brother Mahmud Ali as secretary of Bombay Congress had gone to jail seems to be the correct version.

Members of the Kasuri family played a key role in the newly formed state of Pakistan. As mentioned earlier, Mahmud Kasuri, a leftist lawyer, became a prominent and respected politician in Pakistan. Moinuddin Qureshi, the caretaker prime minister of Pakistan from July to October 1993 was the son of Maulvi Mohiuddin Ahmad Kasuri, the eldest brother of Maulvi Mohammad Ali and Maulvi Mahmud Ali.

The Kasuri family clearly fell out with the Congress and became supporters of the Muslim League. The career trajectory of Maulvi Mohammad Ali Dharavi in colonial India left a trace of his parting of ways from the Congress. Decades after working for the Afghanistan ruler, in a remarkable turn, he joined the British administration working as an inspector of Enemy Trading in the Commerce Department in Calcutta in 1940.

It seems he was recommended for the job by Sir Muhammad Zafarullah, who was a commerce member in the Viceroy’s Council. The Intelligence Bureau raised objection on the ground that “Mr Muhammad Ali, his father the notorious Maulvi Abdul Qadir Kasuri, and his brother Mohi-uddin alias Barkat Ali all have a very seditious record.” The Intelligence Bureau wanted his appointment to be terminated.

Sir Muhammad Zafrullah was approached by the home secretary about the past activities to which he replied that Maulvi Mohammad Ali was now inclined towards the Muslim League. Sir Muhammad Zafarullah said that it was for the Intelligence department to take a decision on Maulvi Mohammad Ali based on the information they had. Ultimately, despite reservations of the Intelligence Bureau, the commerce department took the decision in October 1940 to keep him in the job.

There are no details of why the change in hearts of his uncle and father towards the Congress, but Maulvi Mohammad Ali Dharavi’s passport tale tells a tale of the family’s close link with the Congress and the Independence struggle.

As Kasuri says in his book: “Unfortunately, it is not generally known to the younger generation in Pakistan that there were a large number of Muslims who were leaders in the Indian National Congress that included the founder of Pakistan, Quad-i-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah.”

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.