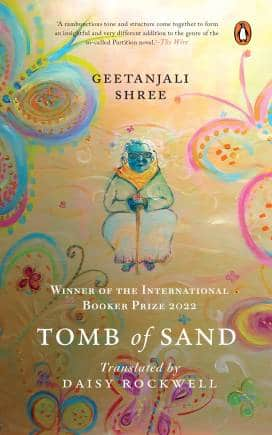

The English translation of Geetanjali Shree’s 2018 novel Ret Samadhi, Tomb of Sand by Daisy Rockwell, has won this year’s International Booker Prize, becoming the first South Asian novel to achieve this feat.

A monumental literary work, Shree’s novel is particularly notable for breaking several binaries. While the writer upends the borders and pushes boundaries through her eclectic use of language, the adroit translator preserves its echoes—dhwani, as Shree puts it—in the translation.

Stories and language

It is often believed that stories need a structure to live. They thrive in definitiveness. In the age of creative writing MFAs, telling a tale can be administerial almost, as if one must complete a checklist: set the story somewhere, define characters, explain their motivations, enumerate conflicts, offer a resolution, provide an inevitable conclusion, and use a language to weave all of this.

A structure is also a border of sorts. To be accepted and celebrated as a storyteller, one must exercise caution. Stay within permissible limits.

Shree does away with all this in Ret Samadhi. First, she lets the “tale tell itself”, because, as she notes, “once you’ve got women and a border, a story can write itself”. In that sense, it’s a queer book from the very first page.

Second, it’s a tale involving an 80-year-old woman (Ma) who has lost her husband. Depressed, she turns her back to her family. Literally. The family takes this stubbornness as a childlike quality that most old people exhibit, but little do they know that soon Ma would metamorphose into many things that they’ll find hard to grasp.

No matter how persistently her family tries to encourage her to take interest in life anew, she decides to take a samadhi—an in-between state of being. Another queer juncture in the book. This neither-here-nor-there tale soon allows Ma to pass through the wall. Bizarre? But that’s fiction for you. You embrace everything if it’s rendered in masterful language—a quality that Shree demonstrates in abundance and Rockwell repeats in the book's English avatar.

Hypervisible invisibles

Hypervisible invisibles

While Ma is omnipresent in this narrative, two-seventh into the novel, two women gain prominence in this narrative: Beti and Rosie Bua. Beti is a feminist, a modern woman—she ran away from home and is a freelancer now, a “mistress of her time”.

Rosie Bua is a Hijra. She used to visit Ma’s home frequently for Holi baksheesh, but when the latter moves to Beti’s flat, their bond transcends the banal conversations they had had previously. It is strange, queer, somewhat odd, the way Rosie has barrelled into their lives as a “gust of fresh wind”, Beti thinks.

One day when Ma fell ill and Beti went to check Rosie Bua’s whereabouts as Ma wanted to see Rosie Bua, Beti was shocked to see a man—Tailor Master Raza, who she thinks looks exactly like Rosie. Baffled, she can’t settle on an appropriate pronoun for Rosie/Raza, while Raza tries hard to give her the impression that she’s talking to a stranger.

Also read: Where Ret Samadhi / Tomb of Sand derives its power from

Unlike many writers, Shree doesn’t employ Rosie to leverage a queer character’s traumatic life to advance the plot. Perhaps the way Rosie is weaved into this narrative, no one else is. It’s the sheer cleverness of its storyteller that not only she gets the character and its background thoroughly right, but she also pens it with empathy.

Now: a Hijra is our neighbour. When he stays with the family, he is their son. Else she becomes who she wanted and desired to be all her life: a woman. She lives like an outcaste. No one interacts with her. Only when she’s in a ‘man’s clothes’ is respectability to at least talk (without making an eye contact) to him rendered to him.

Queers are hypervisible-invisibles. A point that Shree subtly notes in the novel. Note what an inspector says when Ma and Beti go to file Rosie’s missing person’s report: “But the folks in the neighbourhood say he’s been coming around in men’s clothing lately. That way, the dogs and the children probably give him a pass.” It’s this everyday violence that a queer body averts to survive.

When they don’t get any help from the police, KK — Beti’s partner — decides to write Rosie’s story for a newspaper. He is surprised that the story makes it to print, but the part where he mentions the third-gender and social acceptance is missing. The newspaper editor tells him that it’s “useless from the perspective of reader interest” and recommends writing “a long article about it for an academic journal” if he wishes to. Lesson learnt: Not only do queers’ stories get sanitised this way but also the decision that how much should audience consume is also made on their behalf.

There’s an inherent fear in socialising queer lives. It has always been. Because being queer is a sort of freedom, too. And being free is associated with recklessness, something beyond control, which you can’t regulate and monitor, which is why women and queers are policed, silenced, and murdered, and borders are drawn, violence inflicted. It’s easier to democratise policing than to legitimise peace and freedom.

In telling multiple stories involving the everyday queerness in an Indian household — figures like Lachhu Chacha and artists like Bhupen, who render a feminine side to his male portraits — Shree makes a case for such a free world. Porous, free, and welcoming.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.