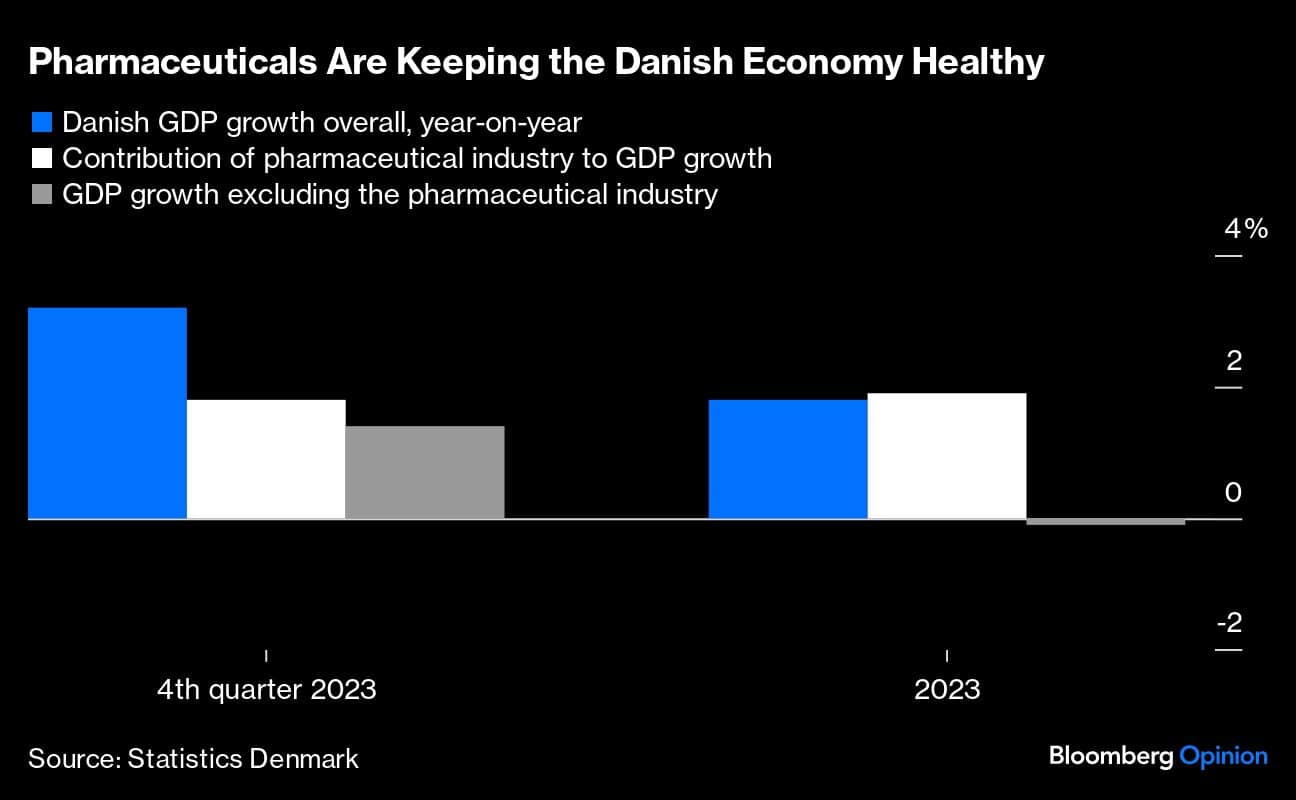

From both a biomedical and economic point of view, the success of the new class of weight-loss drugs is something to behold. Not only are they a remarkable scientific achievement, but — in the case of Ozempic and Wegovy, both made by Novo Nordisk — they are a huge boon to the Danish economy. The Danish pharmaceutical industry kept Denmark from falling into a recession last year.

The dependence of some mid-sized economies on a single commodity, often related to oil or natural gas, is a familiar story. The new twist, which may become increasingly common, is a national economy dependent on a single company — not a natural resource. This will lead to some fundamentally new economic and political dynamics.

One early example of this phenomenon is Nokia in Finland. Finland is a small country, and Nokia’s global sales of mobile phones were such that by 2000, the company accounted for about 4 percent of national GDP and almost 70 percent of the value of the Finnish stock market. In 2013, having failed to keep up with new technology, Nokia was bought by Microsoft.

Will there be more stories like Nokia’s and Novo Nordisk’s? Almost certainly. Many of the world’s best governed countries, which create the legal and economic stability crucial to business success, have populations of between 5 million and 20 million. And the more globalisation proceeds (international trade still is expanding in most economic sectors), the larger such companies can become.

National dependence on a single commodity, of course, can have serious downsides. But dependence on a services-based company is different. For one thing, commodity prices often are set by world markets, and the producing country cannot do much to influence revenue other than choosing how much to produce and sell. A service-based firm is fundamentally in charge of its own destiny, making regular decisions about product quality, marketing and expansion into new lines of business. The skill of company management is critically important.

For related reasons, commodity production is usually easier to nationalise: Natural resources are literally part of the national landscape, after all, and it’s not terribly complicated to dig stuff up from the ground. Chilean copper is owned by the Chilean government; not even the Pinochet-era market-oriented reforms privatised the sector. Middle Eastern oil and gas resources typically are owned by national governments. Inefficiencies in production persist, but those enterprises are commercially successful.

Government attempts to manage a biomedical company, or a major AI company for that matter, would probably not work. Private-sector management thus becomes ever more important for the economic growth of these small to mid-sized countries.

And while it is better for a country to have one big, successful company than not, such a company — such as Nokia in Finland — does put the domestic economy in a somewhat precarious position. Politically as well, that company will have a fair amount of leverage over domestic decisions. It is noteworthy that Novo Nordisk has a very large philanthropic fund, worth more than $100 billion by one estimate. The mere option of spending some of that money in Denmark gives the company further influence over politics and public opinion.

The net result might be more “crony capitalism” — which, to be clear, is preferable to socialism — in mid-sized countries.

Abroad, as the demand for these weight-loss drugs continues to grow, people may start identifying Denmark with pharmaceuticals — just as many people identify France with wine or cheese. The longer-run image of Denmark may shift at home as well, perhaps in a manner that encourages further successes in the biomedical sector.

There are other small- and medium-sized countries with the potential for spawning dominant corporations: Sweden, the Netherlands, Ireland, Singapore and Israel, among others. Perhaps Uruguay could achieve such a position with a successful Latin American company. The US, at the state level, has a long history of highly influential corporations. Walmart, for instance, plays an outsized role in the economy of the state of Arkansas, especially in the area around its headquarters in Bentonville.

Does the rise of the dominant firm necessarily mean a decline in power of the nation-state? It’s too soon to say. What’s clear is that the governance landscape is becoming more crowded and harder to manage. The old fear was that globalisation would make national economies harder to steer, tax and regulate. The new reality is that the outsized domestic successes can do that, too.

Tyler Cowen is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. Views are personal, and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Credit: Bloomberg

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.