Microfinance is apparently grappling with high NPAs going by the report of a rating agency tracking the sector. It says NPAs have jumped to about Rs 61,000 crore in March 2025 (16% of outstanding). This looks a huge number; RBI’s Financial Stability Report of December 2024 had placed stress at a more modest Portfolio at Risk (PAR) value of 4.3%, though as of September 2024.

MFIN, one of the recognized self-regulatory organizations (SROs), also reports rising stress, with the 180-day PAR going up to 9.7% in December 2024. Perhaps NPAs jumped up in the last quarter. The consensus however seems to be that excessive indebtedness, high interest rates and coercive recovery practices were causing the defaults. The regulatory response was predictable.

Signs of Trouble Lead to Regulatory Tightening

The history of regulation here is interesting. The initial crises in the sector such as borrower suicides, competing state laws, usurious interest rates and aggressive lending seemed to have forced RBI’s hand and now nearly 95% of the lenders (banks, SFBs, NBFC-MFIs and NBFCs) are regulated. It was only a few short steps before full-fledged norms encompassing capital, indebtedness, repayment capacity and asset quality norms came. But with RBI now moving to a principle-based approach, it has left the job to SROs such as MFIN.

MFIN’s guardrails issued in June 2024 saw a tightening of norms- freezing lending to clients with overdue greater than 90 days, now reduced to 60 days, limiting the number of microfinance lenders to a client to four, total microfinance loans to a client capped at Rs. 2 lakh- all of which had the effect of slamming on the brakes on a sector that was used to easy credit and multiple lenders vying for the same borrowers.

Gross loan outstanding fell from Rs 4.4 trillion in March 2024 to Rs 3.9 trillion in December 2024 and to Rs 2.8 trillion in March 2025. It was believed that lenders were paring exposure due to high NPAs but MFIN’s report is interesting. It said that its norms were responsible for the credit curtailment and even went on to say that the sudden drying up of credit had led to inflated values of PAR.

At Its Heart, It’s a Financial Inclusion Tool

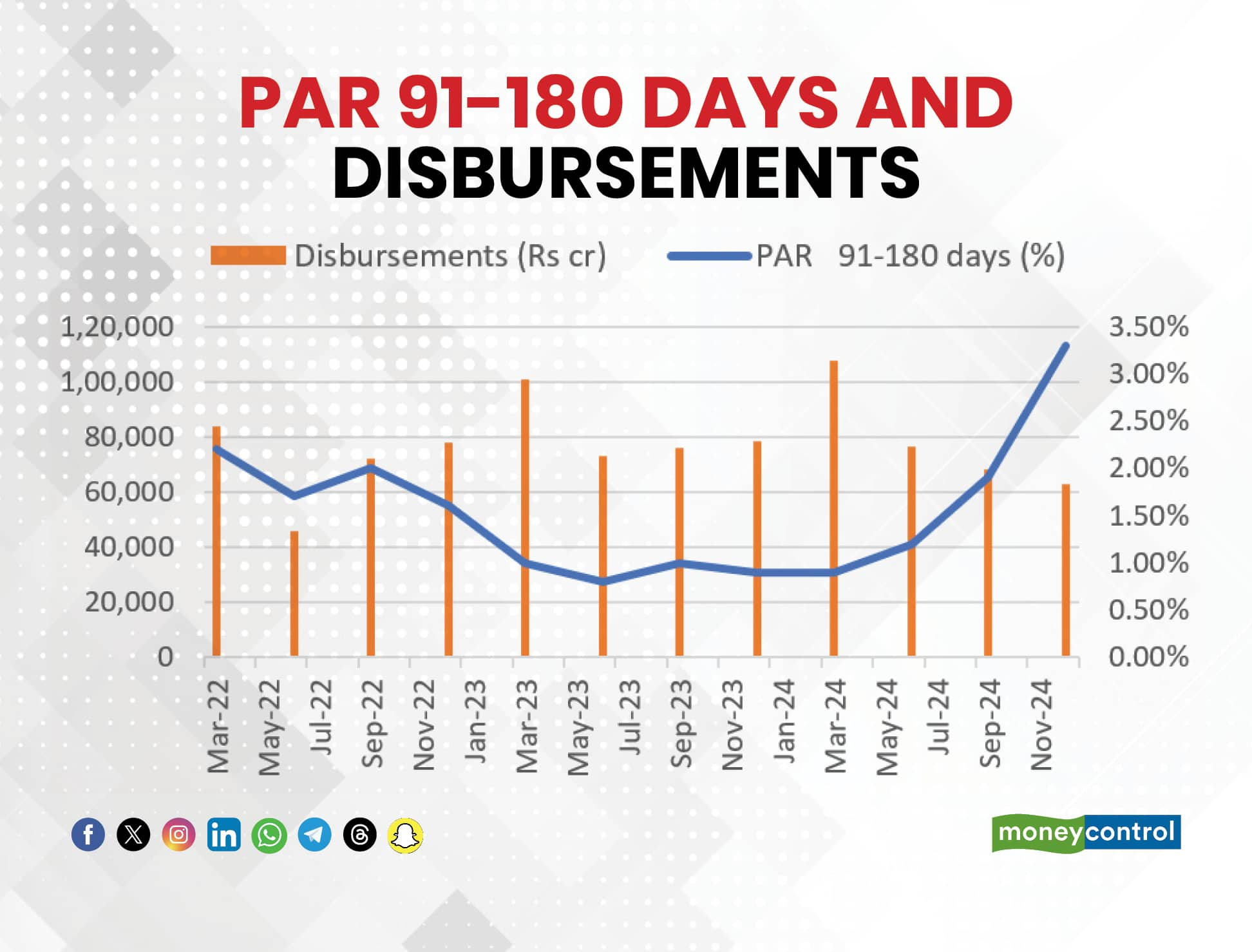

Disbursements and PAR data appear to validate this. There was a sharp uptick in the PAR ratio (91-180 day) from June 2024 as disbursements declined around the same time. There were other pointers too, the key one being the fact that while cumulative disbursements went up by Rs 11.5 trillion between 2021-22 and 2024-25, loan outstanding went up to only Rs 2.8 trillion suggesting a significant level of rollover financing. This is not unexpected given that nearly 20% of the sector’s loans are short-term (1-18 months) and another 49% under 18-24 months. These are important to understand the default story.

The focus on indebtedness and interest rates also distracts from a key feature of microfinance sector that sets it apart from conventional borrowers. It is, at heart, an anti-poverty and financial inclusion tool aimed at improving rural incomes, especially of women. The official definition- a collateral-free loan to a household earning less than Rs 3 lakh per annum- reinforces this. While qualifying assets criteria initially had prescribed at least 70% of loans for income generation activities, the later definition seems to have made it purpose-agnostic.

The government has also adopted it as part of its poverty alleviation program, implementing it through the DAY-NRLM program.

A Model Revamp is The Need of The Hour

The irony cannot be missed. It was low income and low borrowing capacity that had caused financial exclusion in the first place, but the same are coming back to bite now. Rural incomes are extremely difficult to estimate. The MFIN in its India Microfinance Review for 2023-24 says that that it derives income from consumption expenditure data in the HCES surveys. The data is revealing and shows the inadequacy of rural incomes. Not to downplay the role of high interest rates or excessive debt, but low incomes can be a fundamental cause of stress, especially when financing drops off.

To be sure, rural incomes are also a function of economic cycles, but the issue is about the impact that four decades of microfinance has had on rural incomes. The MFIN report points out that the impressive fourfold rise in average rural MPCE from Rs 1430 in 2011-12 to Rs 4122 in 2023-24 still translated to an annual income of less than Rs 3 lakhs for about 95% of rural and 70% of urban households. This is the current threshold for microfinance borrowing which means that a large section of rural populace still required microfinance. This raises the question of whether microfinance had actually succeeded in creating sustainable livelihoods or had only provided sustenance support.

The sector itself seems to be at the cross roads; its mission is still anti-poverty and financial inclusion but the current milieu seems geared more to a commercial credit model. The issue is not about regulation but about fit and granularity. The problems of excessive debt, aggressive lending, lending rates or recovery practices can be addressed by regulation, but for the mission itself, namely, boosting rural incomes through creating livelihoods, a policy rethink and model revamp are essential, not more regulation.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.