Excerpted with permission from the publishers How We Grow Up: Understanding Adolescence Matt Richtel, published by Mariner Books / Harper Collins India

The Man Who Put Adolescence on the Map

THE TURN OF THE CENTURY BROUGHT A NEW ADOLESCENT SCIENCE, PLUS CRACKPOT THEORIES

G. Stanley Hall had a broad forehead, thin hair on top, a bushy beard and mustache. In pictures, wearing a vest, coat, and necktie, he looks every bit the part of the president of Clark University and professor of psychology and pedagogy. Pedagogy is the art and science of teaching. Dr. Hall looks like a serious man about to give a lecture.

He put adolescence on the map. He was its midwife.

The year was 1904. Dr. Hall wrote a handful of books, including Life and Confessions of a Psychologist, Recreationsof a Psychologist, and Jesus, the Christ, in the Light of Psychology.

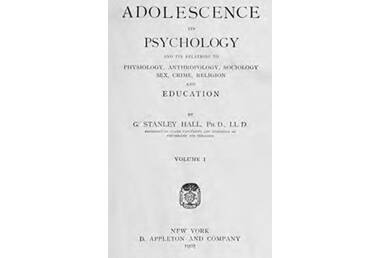

But this was his magnum opus:

Adolescence: Its Psychology and Its Relations to Physiology, Anthropology, Sociology, Sex, Crime, Religion and Education Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library at Yale University.

Adolescence: Its Psychology and Its Relations to Physiology, Anthropology, Sociology, Sex, Crime, Religion and Education Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library at Yale University.

Dr. Hall was not a man short on ambition. Or audacity. The man was bold in his statements.

For example, in this book’s preface, he describes childhood as a period in which children are essentially indistinctive creatures. “The elements of personality are few,” and in childhood, “reason, true morality, religion, sympathy, love, and aesthetic enjoyment are but very slightly developed. Everything, in short, suggests the culmination of one stage of life.”

Dr. Hall saw children as nondescript, generic creatures, organisms on a manufacturing line awaiting shaping by society. Dr. Hall had some noxious things to say, and you haven’t heard the worst of it. But he also made some observations that have stood the test of time, and the mean-spirited and wrongheaded way he characterizes childhood is important for understanding his view of the adolescent and the transformation a person undergoes. So onward with the nasty stuff !

• • •

What Dr. Hall liked about children was they can be easily programmed, taught, instructed, instilled with ideas, culture, and education.

Never again will there be such susceptibility to drill and discipline, such plasticity to habituation, or such ready adjustment to new conditions. It is the age of external and mechanical training. Reading, writing, drawing, musical teaching, foreign tongues and their pronunciation, the manipulation of numbers and of geometric elements, and many kinds of skill have now their golden hour.

For readers who are saying, “Hmm, this guy sounds like a whole bunch of fun,” it gets better. The teaching method, he writes, “should be mechanical, repetitive, authoritative, dogmatic.”

Woo-hoo! I can just see the lines out the door to sign up for Dr. Hall’s Petrifying Elementary School.

The reason that Dr. Hall felt children must be taught with such dogmatic repetition was because these pliable creatures were heading to a period of terrible unrest, suggestive of “some ancient period of storm and stress.”

Dr. Hall thought that adolescents were going through a period that replicated the evolution of humankind, and he was not isolated in this important (but totally wacko) theory. Here it is:

• • •

At the period, a question raged in science about whether individual human beings, as they developed, were destined to play out a version of human evolution. In other words: Did a single individual, over the course of life, mimic the way human beings evolved as a species? This concept was called “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny.”

This clunky phrase was hugely important in explaining what scientists like Dr. Hall thought they knew about adolescence.

“Ontogeny” refers to the development of a single person, an individual. “Recapitulates” means to copy or repeat.

“Phylogeny” means the experience or history of the species. “Ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny” means that an individual’s development repeats or copies or mirrors the evolution of the species. (Plus, it rhymes!)

To influential thinkers like Dr. Hall, it meant that the human species had evolved to become more civilized only after going through a primitive period that was childlike—simple, selfish, almost helpless, like an infant or a child. To grasp this thinking, picture a planet populated with humans as innocent and clueless and vulnerable as a class of kindergartners. This is how early man was seen by thinkers like Dr. Hall.

In this philosophy or theory, the reason that individual children ex- perience childhood is because they are mimicking the development of the species. In their genetic coding, they hold an imprint of this deep past that they must go through as if passing a series of gates, ordained by our nature. Dr. Hall believed that “infants are helpless because that’s how the species started out,” said Dr. Laurence Steinberg, a professor at Temple University and one of the most influential thinkers about modern adolescence.

Then would come the species’ period of adolescence—a period of fighting, angst, a battle within self and against others aimed at shedding that childlike nature while discovering a new path, the one to a higher, civilized nature. Picture a period in human history with a whole bunch of teenagers, the entire land dotted with stubborn naysayers emerging from the cocoon of innocence, forcefully shedding the veil of a sim- ple nature in order to see a greater purpose. The idea for Dr. Hall and others was that the reason individual adolescents acted the way they did—or act the way they do—is because they are replaying this period of emergence in human history.

Only through this dark period would an adolescent ascend to adulthood. “To achieve this great revolution and come to complete maturity,” Dr. Hall wrote, “every step of the upward way is strewn with the wreckage of body, mind, and morals.”

Ooh, tell us what you really think, Dr. Hall.

“There is not only arrest, but perversion, at every stage, and hood- lumism, juvenile crime, and secret vice seem not only increasing, but develop in earlier years in every civilized land.”

No, he’s not mincing his words, although a few of those words might require some interpretation for a contemporary audience. For one, when Dr. Hall writes about “secret vice,” he means masturbation. That was a particularly sore subject for Dr. Hall, who considered it a particularly sinful sign of the adolescent descent into this period of chaos. And it’s happening in “every civilized land.” Not even the young people in the most civilized places are immune from the secret vice.

Indeed, he writes that these adolescent tendencies are at their most primitive when it comes to sex.

“Sex asserts its mastery in field after field, and works its havoc in the form of secret vice, debauchery, disease, and enfeebled heredity, cadences the soul to both its normal and abnormal rhythms, and sends many thousand youth a year to quacks, because neither parents, teach- ers, preachers, or physicians know how to deal with its problems,” Dr. Hall wrote.

There’s that secret vice again. (“He was kind of obsessed,” Dr. Steinberg said.)

But Dr. Hall had hope for us all if we could work through adolescence and, at the same time, demonstrate our evolution as a species. Dr. Hall wrote:

We are conquering nature, achieving a magnificent material civili- zation, leading the world in the applications though not in the cre- ation of science, coming to lead in energy and intense industrial and other activities; our vast and complex business organization that has long since outgrown the comprehension of professional economists, absorbs ever more and earlier the best talent and muscle of youth and now dominates health, time, society, politics, and law giving, and sets new and ever more pervading fashions in manners, morals, education, and religion; but we are progressively forgetting that for the complete apprenticeship to life, youth needs repose, leisure, art, legend, romance, idealization, and in a word humanism, if it is to enter the kingdom of man well equipped for man’s highest work in the world.

That is soaring and conforms to many ideas that are coming back into fashion today. Adolescents will take us higher.

“He had some ideas that were wacky and some that were brilliant,” Dr. Steinberg said.

And it’s hard to overstate Dr. Hall’s importance in establishing the field of adolescence.

“Up until Hall, there was an amorphous general notion that there was this period of life that was different. What Hall did was connect a lot of the dots,” Dr. Steinberg told me. “He was the first person to put it all together. There wouldn’t be a scientific study of adolescence without Hall.”

And he wasn’t altogether wrong. Specifically, the two volumes he wrote about adolescence outlined a ton of big ideas, some of which con- tinue to have some merit. Criminal behavior does rise, as well as risk-taking behavior. Masturbation. Stress and turmoil. And what results is a more mature person.

“Adolescence is a new birth,” Dr. Hall wrote, “for the higher and completely human traits are now born.”

• • •

But it wasn’t happening for the reasons he thought, namely the replay- ing of some ancient human development. Not even close.

It would take until very recently to understand those issues, with help from thinkers like Dr. Steinberg, and a new generation of scientists informed by technology that lets us peer into the blood, the brain, the hormones, the biological building blocks that, in turn, give us evidence as to why adolescents really act the way that they do.

This eventually leads to the neurobiology of adolescence and pu- berty. Before these modern revelations, though, there emerged several other important theories about adolescence. A key one came in Vienna in 1958. It had largely to do with sex.*****

Matt Richtel, How We Grow Up: Understanding Adolescence Mariner Books / Harper Collins India, 2025. Pb. Pp.336

The transition from childhood to adulthood is a natural, evolution-honed cycle that now faces radical change and challenge. The adolescent brain, sculpted for this transition over eons of evolution, confronts a modern world that creates so much social pressure as to regularly exceed the capacities of the evolving mind. The problem comes as a bombardment of screen-based information pelts the brain just as adolescence is undergoing a second key change: puberty is hitting earlier. The result is a neurological mismatch between an ultra-potent environment and a still-maturing brain that can lead to anxiety, depression, and other mental health challenges. It is a crisis that is part of modern life but can only be truly grasped through a broad, grounded lens of the biology of adolescence itself. Through this lens, Richtel shows us how adolescents can understand themselves, and parents and educators can better help.

For decades, this transition to adulthood has been defined by hormonal shifts that trigger the onset of puberty. But Richtel takes us where science now understands so much of the action is: the brain. A growing body of research that looks for the first time into budding adult neurobiology explains with untold clarity the emergence of the “social brain,” a craving for peer connection, and how the behaviors that follow pave the way for economic and social survival. This period necessarily involves testing—as the adolescent brain is programmed from birth to take risks and explore themselves and their environment—so that they may be able to thrive as they leave the insulated care of childhood.

Richtel, diving deeply into new research and gripping personal stories, offers accessible, scientifically grounded answers to the most pressing questions about generational change. What explains adolescent behaviors, risk-taking, reward-seeking, and the ongoing mental health crisis? How does adolescence shape the future of the species? What is the nature of adolescence itself?

Matt Richtel is a health and science reporter at the New York Times. He spent nearly two years reporting on the teenage mental-health crisis for the paper’s acclaimed multipart series Inner Pandemic, which won first place in public-health reporting from the Awards for Excellence in Health Care Journalism and inspired his book How We Grow Up: Understanding Adolescence. He received the Pulitzer Prize for national reporting for a series of articles about distracted driving, which he expanded into his first nonfiction book, A Deadly Wandering, a New York Times bestseller. His second non-fiction book, An Elegant Defense, on the human immune system, was a national bestseller and chosen by Bill Gates for his annual Summer Reading List.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.