“To anyone I’ve offended, I just want to say, I reinvented electric cars and I’m sending people to Mars in a rocket ship. Did you think I was also going to be a chill, normal dude?” asked Elon Musk on Saturday Night Live in 2021. The 670-page Elon Musk biography by Walter Isaacson attempts to answer that question.

Isaacson is one of the most respected journalists and biographers around, having chronicled the life stories of famous men like Albert Einstein, Leonardo da Vinci, Benjamin Franklin and Steve Jobs. So it didn’t really come as a surprise when it emerged that he would be the biographer of Elon Musk, easily one of the most controversial figures of this generation.

For two years, Isaacson had complete access to Musk, not just in a personal one-on-one capacity, but he was also allowed to hang around when Musk was in the thick of business at all of his professional ventures. The thick book, divided into 95 chapters, chronicles Musk’s life from his early days in South Africa to his latest shenanigans as the owner of Twitter, now X. Isaacson has deftly managed to document things chronologically, even as Musk juggled six ventures simultaneously. It’s a tricky undertaking and Isaacson delivers to a large extent.

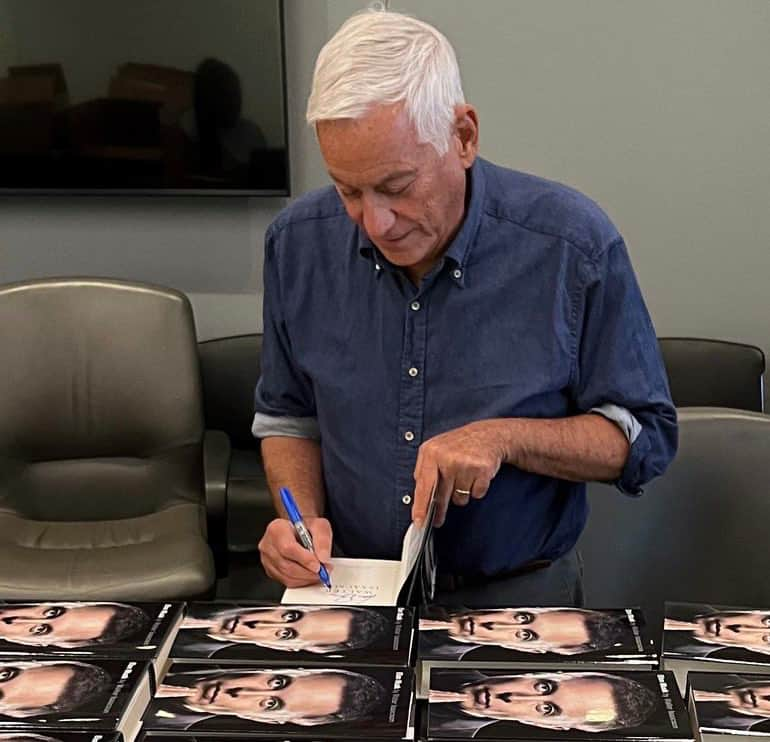

Walter Isaacson. (Image source: X/@WalterIsaacson)

Walter Isaacson. (Image source: X/@WalterIsaacson)

Hits

While the book goes into many intricate details, a few larger themes do emerge and Isaacson makes it a point to keep connecting major events to them.

The top theme is Musk’s troubled childhood and his relationship with his abusive father, Errol Musk. This paired with Musk admitting he has Asperger’s syndrome is used as a lens to look at most things that are written about in the book: from Musk’s inability to deal with human emotions to his ‘ultra hardcore’ work ethic to his propensity to always attract drama to even him going out of his way to love his children. Musk’s inability to savour moments of success or happiness and seek out newer problems to solve, almost try to portray him as a war-weary soldier who is so used to tackling attacks from all sides that he doesn’t know what to do when things are calm.

Isaacson profiles each of Musk’s ventures. From the early drama at PayPal to the failures of launching the Starship rocket at SpaceX to the nitty-gritties of how Tesla was kept afloat to trying to unpack the importance of the brain-computer interface at Neuralink, Isaacson has you covered. One also gets a ringside view of some internal conversations involving Musk berating his colleagues or flying off the handle on not seeing people in the SpaceX office (on a Friday evening) and this constant sense of urgency with each of his ventures.

Some of these sections definitely can get too dry as a lot of it is pure enlisting of what’s happening and at other times, taking Musk’s word for things. This comes with its own set of risks. Isaacson would learn that the hard way as he was forced to retract one fact that’s been printed in the book. After helping the Ukrainian authorities with Starlink satellites to keep the internet functioning in the war-torn country, Musk was alarmed when it emerged that his satellite internet service was being used to launch attacks. In one instance, Musk claimed in the book that he took a call to disable Ukraine military’s access to Starlink satellites, when he learned that they were going to attack Crimea, as this would lead to an escalation triggering a third world war. But when questioned on Twitter about this anecdote in the book, Musk denied ever disabling Starlink in Ukraine. It’s definitely got Isaacson in a sticky situation.

One thing that does get boring quite soon is the repeated mentions of instances of trying to illustrate how Musk knows more than his subordinates. Every couple of chapters one is bombarded with examples of how Musk cut down the costs of a certain manufacturing component or how Musk set an unlikely deadline that was honoured.

An interesting aspect of the book is trying to contextualize how Musk’s interest in artificial intelligence had its roots in a conversation he once had with Google founder Larry Page. When Musk tells Page that human consciousness “was a precious flicker of light in the universe and we should not let it be extinguished”, Page dismisses it as sentimental nonsense. This would propel Musk to invest in OpenAI (creator of ChatGPT), then have a fallout with its founder Sam Altman and eventually form his own AI company called X.AI.

Getting to know Musk through his ex-wives and girlfriends shines a light on aspects of his personality that only some who were very close to him have been witness to. There’s constant mention of a ‘demon mode’ where he just stares blankly into space or is processing things, and is a time when you shouldn’t disturb him. Among his 10 kids, X (his son with singer Grimes) is most prominently featured throughout the second half of the book accompanying Musk on satellite launches, award ceremonies and Tesla factory floors. But one wonders if featuring X in the book is Musk’s way to portray that he’s not his father and to make up for the hurt he feels due to the estrangement of his eldest child, Jenna.

Misses

Isaacson has interviewed hundreds of people for the book, but when you look at the names, it’s mostly Musk’s close relatives, friends, well-wishers, ex-wives and some disgruntled former top employees. There’s barely any perspective from the bottom up at any of the companies featured. Reading the sections on Tesla makes it look like it was about Musk taking huge bets (which he was) and firing those who weren’t onboard with his vision. But there’s nothing about the working conditions or reports of discrimination that took place on the floors. Even with the detailed chapters on Twitter, there’s little perspective from the people who were fired from one day to the next and who weren’t big shots. Isaacson often repeats Musk’s “if we don’t do x thing, we will never reach Mars", without really questioning that. Musk talks about the “woke mind virus”, but never does Isaacson ask him to explain what exactly he means by that. Musk’s experiments with cryptocurrency, where Tesla clearly indulged in pump and dump, have been completely ignored in the book barring a passing mention.

As you are halfway through the book, it makes you feel like there was a Faustian pact signed, when Isaacson agreed to have unfettered access to his subject. Sure, Isaacson does point out how Musk has lied throughout his career to secure funding, whether it's getting full self-driving in Tesla cars or getting humanity to Mars. But it’s heavily outnumbered by the times he tries to put the blame for all his flaws on things other than Musk. There are many examples of books (Tim Higgins’ Power Play and Brad Stone’s Amazon Unbound, to name two) where the authors didn’t get access to the subject but were still able to do data-backed reportage on many issues facing these companies.

I loved reading the chapters since Musk decided to take over Twitter, and how he was caught off-guard as unlike his previous engineering-led ventures, where he was on top of things and had seen these ventures grow gradually, Twitter was a whole other beast. Engineering is just one aspect, but the social layer that involves dealing with tricky things like censorship and ensuring the product generates enough revenue to justify the $44 billion purchase, has definitely proven a thorn in Musk’s cap. It’s still a year in, so maybe it’s too early to judge. But one can’t help saying “Yeah, right. Like that will ever happen,” when one reads that Musk hopes to quintuple Twitter’s revenues to $26 billion by 2028. Especially since AI has become a shiny new toy since last year that Musk also wants in on. Isaacson mentions how Musk has now begun questioning the “brain cycles spent” on running Twitter. It’s a rare instance of Musk reflecting and almost admitting he screwed up.

This 670-page tome isn’t really a page-turner despite the short chapters and chronological treatment. There is no doubt that it will sell in huge numbers, irrespective of the reviews. If you haven’t already read any of the seven major Musk or Musk-related biographies that have come out before this, this is the one to get.

The two major questions one is left with after completing the book are: “Is Elon Musk becoming his father Errol Musk? Should his reckless behaviour be given a pass, given all that he’s achieved?”

On the last question, Isaacson concludes by saying he doesn’t find it necessary that one needs to be an asshole to justify their achievements. But then he ends with, “As Shakespeare teaches us, all heroes have flaws, some tragic, some conquered and those we cast as villains can be complex.”

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.