The seeds of East Bengali people’s fight for their language were sown in the 1952 Bhasha Andolan (Bengali language movement), which became the sine qua non for the muktijuddho (1971 Liberation War), when East Pakistan sought linguistic and cultural autonomy from Yahya Khan-led West Pakistan, steered by one man, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (1920-75).

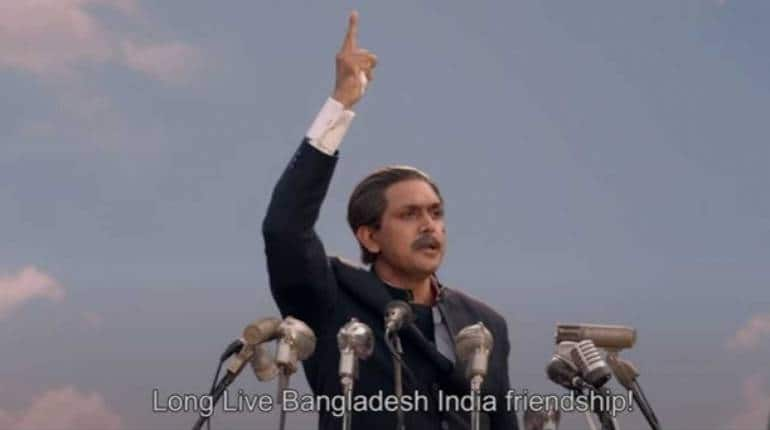

Few world leaders are like Mujibur Rahman, fondly called Bangabandhu (friend of Bengal), whose life-long fight, which cut short his life, has been for his people and their mother tongue. Perhaps, nowhere else in the world has a nation been eked out for a language, not politics or religion. “I’m a Bengali. I’m a human being. I’m a Muslim, who only dies once, not twice,” the rousing call of the Bengali nationalist from his famous March 7, 1971 speech to a gathering of 2 million in Dhaka has been reimagined, along with his life as a revolutionary politician and a family man, in Shyam Benegal’s new film, his first Bangla-language film, Mujib: The Making of a Nation, which releases across Indian theatres on October 27, in Hindi and regional languages.

It stars Bangladeshi actor Arifin Shuvoo in the titular role of Rahman, the father of their nation, the first Bangladeshi prime minister, who, at age 55, along with his entire family, including his youngest son Sheikh Russel, aged 10 — barring his two daughters (Sheikh Hasina and Sheikh Rehana) who were away, studying in Europe — were gunned down at their Dhanmondi (Dhaka) residence on the very date India gained independence from the British.

The revolution consumed its hero, a free nation was created, and its foremost champion paid in blood. Mujibur’s life echoes a Shakespearean tragedy and Greek tragedy, his hamartia or tragic flaw was his abiding and insurmountable love for his countrymen, to dismiss that they could do him harm, to ignore that the sword of Damocles was hanging over his head.

When the respective governments of India and Bangladesh decided, in 2019, to jointly produce a film on Rahman, to commemorate 50 years of the Liberation War, their best bet was Benegal — the creator of biopics and documentaries on leaders of their fields (Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, Satyajit Ray) — to realise on film the epic life-story of the towering Bangabandhu. COVID-19, however, played spoilsport.

With Mujib, Benegal returns to theatres after 14 years since Well Done Abba! (2009). His debut Ankur (1974), which launched many faces in the Hindi film industry and completes 50 years next year, had sown the seedling of the parallel cinema movement in India, watered with his social and human documents on film that followed.

Benegal is only the second Indian filmmaker to have had the backing of these two nations’ governments to make a collaborative film after the maverick auteur Ritwik Ghatak — Mujib is only six decades apart from Ghatak’s Titash Ekti Nadir Naam (1973). The Dhaka-born, Kolkata-based eternal melancholic refugee Ghatak’s utopian desire was a unified Bengal, which was unnaturally divided by the Radcliffe Line. While Ghatak paid a metaphorical ode to East Bengal with his literary adaptation, Benegal pays an emotional tribute. The dialects spoken on either side of the border, in epaar Bangla (West Bengal) and opaar Bangla (East Bengal or Bangladesh) are starkly different, the eternal realist Benegal went the extra mile to make the film in the Bangladeshi dialect.

Guru Dutt’s cousin, Shyam Benegal, who, at 88, is, perhaps, the oldest filmmaker alive, across the world, actively making movies. Despite being on dialysis, he leads a disciplined 9-to-5 work schedule. Perhaps, he’s channelling the never-give-up energy of that adolescent swimmer who went to Calcutta for a championship once, watched Ray’s Pather Panchali, in an alien language (Bengali), revisited it a dozen times, and returned a convert. Excerpts from an email interview:

Ritwik Ghatak certainly did. He was brilliant, an eccentric genius.

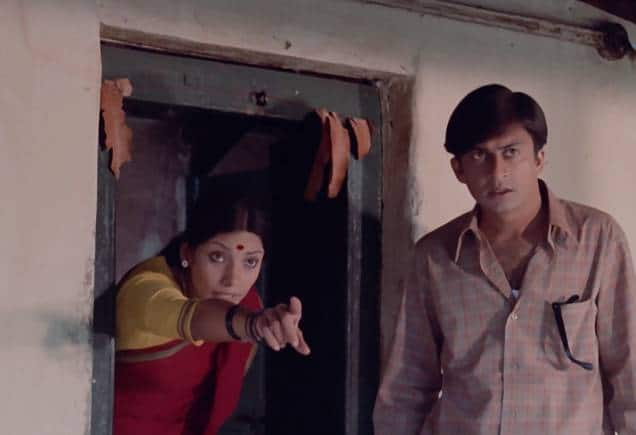

A still from Ritwik Ghatak's 'Titash Ekti Nadir Naam' (1973).You are contextually and linguistically removed from Bangladesh. When the government approached you to make the film, what were your initial thoughts?

A still from Ritwik Ghatak's 'Titash Ekti Nadir Naam' (1973).You are contextually and linguistically removed from Bangladesh. When the government approached you to make the film, what were your initial thoughts?Mujibur Rahman was an extraordinary political leader and uncompromising patriot. What fascinated me was that he was not only an outstanding political leader, but equally, a family man whose domestic life was at no time neglected as is often the case with political leaders.

A still from the film 'Mujib'.For a film on a personality, the bedrock of whose life’s struggle was bhasha (language), how much of a roadblock was bhasha (the language of communication) for you, while making your first Bangla-language film, in the script, on the set, during shot breakdown?

A still from the film 'Mujib'.For a film on a personality, the bedrock of whose life’s struggle was bhasha (language), how much of a roadblock was bhasha (the language of communication) for you, while making your first Bangla-language film, in the script, on the set, during shot breakdown?I had excellent advisors (Bangladesh’s Sadhana Ahmed is dialogue writer, script supervisor and dialogue coach on the film) who had thorough knowledge of the different dialects and idioms of the Bengali language. It would not have been possible since I do not have any real knowledge of Bengali.

What kind of research did you make your team undergo?My research team both in Dhaka and Mumbai studied contemporary history of Bangladesh extensively.

A still from Mujib.Bangladeshi cinema historically began years before the nation was formed in 1971. Did you get a chance to watch old Bangladeshi films about the muktijuddho (Liberation War) and Mujibur Rahman?

A still from Mujib.Bangladeshi cinema historically began years before the nation was formed in 1971. Did you get a chance to watch old Bangladeshi films about the muktijuddho (Liberation War) and Mujibur Rahman?Not very much. One of my filmmaker friends, the late S. Sukhdev, made an excellent documentary film (secretly, while) travelling with a Mukti Bahini Squad during the Bangladesh Liberation War (the footages were later turned into the documentary Nine Months of Freedom, 1972).

Tell us about the onscreen Bangabandhu, Arifin Shuvoo (who was seen in Kolkata filmmaker Ranjan Ghosh’s Ahaa Re, 2019, opposite Rituparna Sengupta), who’s a beefed-up Bangladeshi star seen in action films and romances.He is brilliant and has given an outstanding performance.

Arifin Shuvoo in and as Mujib.Your movies are also remembered for the iconic women characters: Laxmi, Sushila, Bindu, Usha, Kasturba..., your women were flawed individuals. While there might have been enough material available on Mujibur Rahman, was there ready material available on his wife Begum Sheikh Fazilatunnesa Mujib (played by Nursat Imrose Tisha)?

Arifin Shuvoo in and as Mujib.Your movies are also remembered for the iconic women characters: Laxmi, Sushila, Bindu, Usha, Kasturba..., your women were flawed individuals. While there might have been enough material available on Mujibur Rahman, was there ready material available on his wife Begum Sheikh Fazilatunnesa Mujib (played by Nursat Imrose Tisha)?Clearly most of the material about Mrs Mujib, Begum Sheikh Fazilatunnesa Mujib, came from what my writers and I heard from the present Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina who happens to be the daughter of Mujib.

Nusrat Imrose Tisha as Begum Sheikh Fazilatunnesa Mujib in a still from 'Mujib: The Making of a Nation'.You have worked with the best talents in the industry, cinematographers Govind Nihalani, Ashok Mehta, VK Murthy, music wizard Vanraj Bhatia. Besides your long-time collaborator writer Shama Zaidi (who has co-written Mujib, along with actor-writer Atul Tiwari), do you miss working with your old friends?

Nusrat Imrose Tisha as Begum Sheikh Fazilatunnesa Mujib in a still from 'Mujib: The Making of a Nation'.You have worked with the best talents in the industry, cinematographers Govind Nihalani, Ashok Mehta, VK Murthy, music wizard Vanraj Bhatia. Besides your long-time collaborator writer Shama Zaidi (who has co-written Mujib, along with actor-writer Atul Tiwari), do you miss working with your old friends?Except for those of my colleagues who have passed on, I work with the same people I have done from the very beginning of my film career.

The film has been shot in Dhaka, Kolkata and Mumbai. While the Bangladeshi flat lowlands terrain is dramatically different from ours, how did you recreate it in a Bombay studio?Most of the film was shot on sets in Film City, Mumbai. We used multiple plates of the Bangladesh countryside to give the effect of the plains.

Indira Gandhi in a screen grab from Benegal's documentary on Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (1982).From one daughter commissioning a film on her father to another — India’s former PM Indira Gandhi (documentary, Jawaharlal Nehru, 1982) to the current Bangladesh PM Sheikh Hasina (feature biopic, Mujib). Did both the daughters vet the minutest details of the respective films for veracity?

Indira Gandhi in a screen grab from Benegal's documentary on Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (1982).From one daughter commissioning a film on her father to another — India’s former PM Indira Gandhi (documentary, Jawaharlal Nehru, 1982) to the current Bangladesh PM Sheikh Hasina (feature biopic, Mujib). Did both the daughters vet the minutest details of the respective films for veracity?They were both excellent and were of great help in putting together details of every life.

Bangladesh is singular to have been carved out as a nation for the sake of a language and culture. Would you say, language and culture matter way more than religion?Most definitely.

A screen grab from Benegal's documentary on Satyajit Ray (1985).You made a documentary on Satyajit Ray, and have said in an interview that films are pre-Satyajit or post-Satyajit.

A screen grab from Benegal's documentary on Satyajit Ray (1985).You made a documentary on Satyajit Ray, and have said in an interview that films are pre-Satyajit or post-Satyajit.Satyajit Ray was a towering filmmaker, whose status in the Indian cinema was much like the status of Rabindranath Tagore in literature.

How to ensure that biopics don’t turn into hagiographies? What advice will you give younger filmmakers about maintaining a critical distance from their subject?An objective view is not hagiographic. One has to keep out subjective predilections and prejudices so that one’s judgement is not coloured by them.

As an audiovisual storyteller, what would you say to those who pigeonhole you as a political filmmaker?Is it necessary to label every filmmaker as either political, social or escapist?

How do you view today’s growing disdain for history and historians? People, even filmmakers, are either not interested in it or are using it in reductive ways, in historical fiction and propaganda films?There are many histories. Each history depends on the point of view of the interpreter.

Roshan Seth as Pandit Nehru in Benegal's televised historical drama series, 'Bharat Ek Khoj' (1988), based on Nehru's book 'Discovery of India', written during his imprisonment at Ahmednagar fort for participating in the Quit India Movement (1942–46).Like there can be no Bangladesh without its first PM Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, in the making of our nation, can there be an India without her first PM Jawaharlal Nehru and his legacy and contribution?

Roshan Seth as Pandit Nehru in Benegal's televised historical drama series, 'Bharat Ek Khoj' (1988), based on Nehru's book 'Discovery of India', written during his imprisonment at Ahmednagar fort for participating in the Quit India Movement (1942–46).Like there can be no Bangladesh without its first PM Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, in the making of our nation, can there be an India without her first PM Jawaharlal Nehru and his legacy and contribution?We are hugely fortunate that we had Nehru. He assured us our place in the contemporary world.

One chapter of your filmography is also a peek into ordinary Indian Muslim lives. Could you have made films like Suraj ka Satvan Ghoda (1992), Mammo (1994), Sardari Begum (1996), Zubeidaa (2001) in our polarised world today?Yes, why not?

Farida Jalal in and as Mammo in the 1994 Shyam Benegal film.Do young filmmakers have to navigate a far tougher time now than what you and your peers did in the ’70s?

Farida Jalal in and as Mammo in the 1994 Shyam Benegal film.Do young filmmakers have to navigate a far tougher time now than what you and your peers did in the ’70s?It is much easier today, with the range of media available — cinema, TV, OTT, etc.

How do you react to the word ‘content’? Has cinema been marginalised in the digital OTT world?The term is often used very loosely in its most generalised sense.

Benegal, and actors Shabana Azmi and Anant Nag, made their debut with 'Ankur' (1974).Next year, your debut film Ankur, the first in your rural reform trilogy, will turn 50 years old. Your thoughts on that film, those times and how the rural subject has vanished from Hindi cinema now?

Benegal, and actors Shabana Azmi and Anant Nag, made their debut with 'Ankur' (1974).Next year, your debut film Ankur, the first in your rural reform trilogy, will turn 50 years old. Your thoughts on that film, those times and how the rural subject has vanished from Hindi cinema now?I [don’t] think about the films that I have already made. It is already in the past, over and done with. It is inevitable that rural subjects will fade, and become less with time. This is because the Indian nation is urbanising with great rapidity.

What was the financial share of the two countries on Mujib?NFDC (National Film Development Corporation, India) financed the film up to 40 per cent and BFDC (Bangladesh film Development Corporation) gave 60 per cent.

BFDC provides annual funding to independent filmmakers, supports films on muktijuddho/Bangladeshi culture. In what way are NFDC and BFDC similar or different?BFDC is doing what needs to be done at present, dealing with subjects that are socially relevant to Bangladesh.

In the ’70s-’80s, the government-backed NFDC fuelled the parallel cinema movement. You have now made films under the old NFDC and the new NFDC, the umbrella company under which four other film bodies have been subsumed. How different have the two experiences been?My experience has been very satisfying.

Are you working on another project? Will it be a biopic?I have no idea.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.