Shall we call it #Salunki or maybe #Dunlaar? Whatever hashtag you choose, chances are the weekend of December 21/22 will go down as a bare-knuckle fight between two heavyweight films.

Is this the closest we have come to Barbenheimer in this country?

Maybe yes, because not only do these two films represent two very different filmmaking cultures and canons, they also represent two studios with different designs in going about making mainstream cinema.

In this battle of the traditional bigwig in Red Chillies (Main Hoon Na, Om Shanti Om, Badla, Darlings) and the latest incredulous kid on the block in Hombale Films (Kantara, KGF), there is also a battle for contrasting ideas of big-ticket moviemaking, provocation and stardom.

This battle between life-affirming wit and masculine gore might be befitting of a year in which Hindi cinema has reluctantly accepted a latitudinal shift in its language.

Soon after their coinciding release dates were announced, there were rumours of a turf war between the makers of Dunki and Salaar for screens. This particular weekend has not two, but three mammoth releases lined up with the much-awaited sequel to DC’s Aquaman – the one good franchise with the studio – also slated to release on the same weekend. It automatically implies a crunch for screen space, in the Hindi-speaking belts where figuring out what might or might not work remains as hard an ask as it remains to mount a project. You know Prabhas and Hombale will rake in the crowds south of Vindhayas but it’s to the north, where the country has seen the greatest multiplex expansion in recent years, that the competition for eyeballs remains far more open.

Salaar releases in Indian theatres on December 22, 2023. (Photo via X/SalaarTheSaga)Hombale Films vs Red Chillies Entertainment

Salaar releases in Indian theatres on December 22, 2023. (Photo via X/SalaarTheSaga)Hombale Films vs Red Chillies EntertainmentIronically, both trailers have underwhelmed. While Rajkumar Hirani has characteristically offered an oblique, rather tame teaser, Salaar feels like a familiar ‘bro-down’ in the colours of the studio’s breakout franchise KGF. In fact, the two films look eerily, and rather disappointingly similar in texture, aesthetic and grammar. Not that the scale looks any less impressive or compelling but there is a sense that Hombale might just double down on the tough-guy shtick it engineered to perfection with the KGF franchise. Though Kantara wasn’t exactly cut from the same cloth, its streak of humour and self-awareness was born from a typically masculine vein of deprecation. It’s unfortunately what the mainstream is.

Unless, of course, if you’re a Red Chillies, a studio that has recently championed off-the-cuff projects like Love Hostel and Darlings, and in Dunki looks as distant from that grim, visceral dispensing of casual violence as any film might have in recent memory. You could argue, Shah Rukh Khan’s Jawan teetered on the periphery of becoming a massy, cantankerous actioner, but it just about does enough to roll back any toxicity that might escape the system. There was, so to speak, enough in it to endear it to audiences looking for something more tender, delicate and life-affirming.

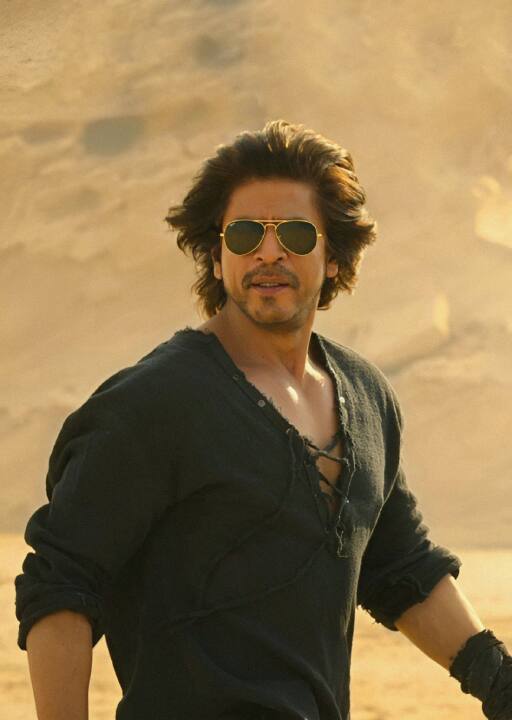

Shah Rukh Khan in Dunki (Image via X.@Roninx___ )Pan-India phenomenon

Shah Rukh Khan in Dunki (Image via X.@Roninx___ )Pan-India phenomenonIt’s debatable if the ‘pan-India’ phenomenon still exists but it is evident that the sensibilities of the southern industries has begun to seep into the palettes of the Hindi belt. The heroes look brasher, bigger than ever, and the space for nuance, softness and feminine energy seems to casually be receding from public view.

Salaar is the poster boy of a new kind of cinema that has planted its feet in our conscience. The cinema of alpha men, of larger-than-life action franchises, evocative world-building and the kind of pulpy, violent elements that make it a sporting contradiction of everything Hindi cinema has been – romantic, soft, self-appraising and dreamy.

With Sandeep Reddy Vanga’s ultra-violent and strategically divisive Animal breaking records, the future of Hindi cinema looks hurtling down a fresh, unseen route. Unless of course if Khan can work his charm for the third time in the same year, and return us to a place of heartfelt innocence, heartbreak and endings cushioned by moral epiphanies.

The grandness of a story is subjective to taste. Sometimes it’s the scale of the setting, the heightening sense of the visuals or the stakes being pursued. A film must also capture the zeitgeist, to be able to become relatable in ways that reality itself isn’t. It’s how Sooraj Barjatya made blockbuster after blockbuster in the post-liberalisation '90s. And why Khan became the epitome of diaspora chic, when love became indistinctly coiled with national identity.

Salaar Poster (via X/@SalaarTheSaga)

Salaar Poster (via X/@SalaarTheSaga)It’s hard to tell if today’s viewer wants cinema rooted in socio-political topsoil or punctuated by greasy battle swords, but in this battle of tones, colours and generational mood, no two films could better play the role of opposites; the old romantic guard vs the rowdy, compelling new version of youthful restlessness.

In an ideal world, both would do ecstatically well, a la Barbenheimer, and inflate the potential of both ideas of cinema. Because let’s be honest, both are needed. The former to sustain the illusion of happy endings emerging from moral chivalry and the latter, so it can shake you awake to the presence of everything that is ugly, unspeakable and stylishly within grasp.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.