As the US slams a backdoor entry for Chinese-made solar panels and the European Union examines trade restrictions on electric vehicles and wind turbines, there’s one point on which most people agree: China’s clean-energy products are cheaper because the sector is being grossly subsidised.

One problem with that theory: There’s no evidence that such subsidies exist. The low cost of Chinese-made green tech isn’t due to anything that the World Trade Organization would consider a subsidy. It’s largely a result of the fact that the country’s vast size, along with the environmental targets the WTO’s rules were written to protect, encourage manufacturers to invest on a scale that puts the rest of the world to shame.

Subsidy accusations get thrown around so freely because they’re a useful bogeyman in trade discussions. Our own industrial support is usually pervasive and popular, though. Few but the most extreme libertarians would object to the $18 billion in government funds that the US provided to help develop a vaccine against Covid-19. European governments have spent €651 billion ($695 billion) since late 2021 shielding consumers from rising electricity prices. Subsidies for fossil fuels last year amounted to $7 trillion, or about 7.1 percent of global economic product, according to the International Monetary Fund.

The ubiquity of subsidies means there’s a high bar to considering them anti-competitive at the WTO. It’s not enough to point to the availability of cheaper land, energy, finance or labour and label it a subsidy: Governments must be shown to be favouring specific industries. Glance through the WTO’s databases for evidence of successful actions against China’s low-carbon technology, and you’ll come up short. Of more than 50 disputes since it joined in 2001, there have been cases involving steel tubes, barley, wine, auto parts and rare earths, among many other products. Just one has related specifically to renewables, a case about wind equipment that’s been dormant since 2011.

That’s not stopped cases being brought at the national and regional level, where circumstantial evidence is sufficient. The US has levied duties of 40 percent or more on Chinese-made panels since 2012, based on claims that its manufacturers were unable to match Chinese competitors because of dumping at below-market prices. That argument looked dubious at the time, and seems even more so in hindsight, considering the way solar prices globally plummeted during the period. Similarly, pressure to open cases is increasing in the EU just as a new anti-subsidy law passed last year enters into force and gives officials fresh powers.

The danger is that these spurious cases will wind up hindering the path to net-zero. Many of China’s trading partners have framed trade barriers locking out its green-power equipment as an energy-security necessity, essential for protecting domestic manufacturers against rapacious undercutting by Beijing’s government-industrial complex. In practice they may simply be raising the amount they’ll have to spend on renewable equipment, while coddling uncompetitive local businesses that haven’t invested sufficiently in the energy transition.

The current shape of subsidy policies is a mess, as Jennifer Hillman and Inu Manak of the Council of Foreign Relations argued in a paper last month. Trade-distorting activity is almost impossible to investigate or police, and countries have largely given up on obligations to report their subsidies to the WTO. We also make no effort to distinguish between support most governments recognize as beneficial when handed to domestic producers — such as ones to lower the price of food and early-stage clean technology — and ones that funnel tax dollars to bloated incumbents. Fossil fuel subsidies, meanwhile, exist in a legal gray area, and have long been immune from the scrutiny given to renewable equipment.

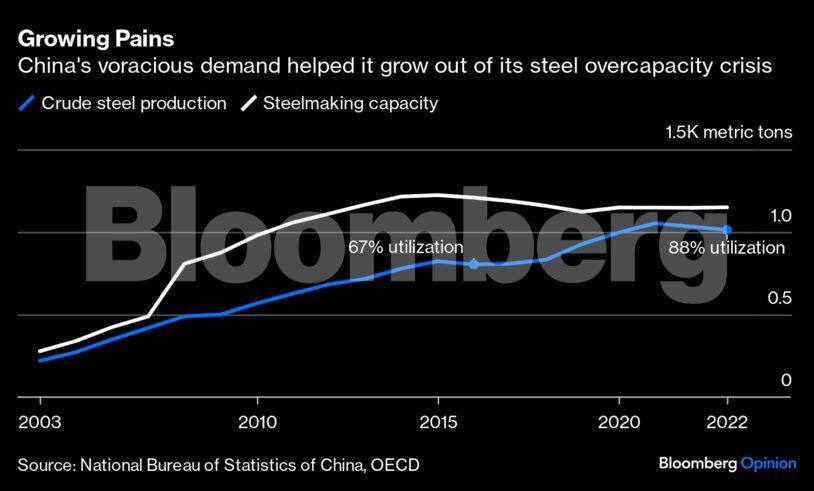

China does itself few favours. The dominance of sclerotic state-owned companies and prevalence of off-the-books financing give ample fodder for trade partners looking to justify protectionist restrictions. The sheer scale of the Chinese economy means that other nations tend to view supply-demand mismatches in conspiratorial terms — such as when steel-mill investments ran ahead of output in the years up to 2015, sparking years of complaints and tariffs. The opacity of the Chinese economy allows other nations to cite its competitive advantages as unfair practices.

Still, the subsidy-rich Inflation Reduction Act in the US and the EU’s REPowerEU plan both suggest that the world is moving in China’s direction of using the public purse to advance clean energy goals.

That’s welcome. Subsidies are just another word for the state using its fiscal might to provide goods that the private sector won’t fund on its own. What’s needed isn’t a blanket ban, but a policy acknowledged by all WTO members that more honestly distinguishes between good and bad uses of such spending. Using state funds to accelerate the energy transition should be no more controversial than paying for other social goods, such as health, education and public security.

That would imply not an arms race on tariffs, but instead a policy of mutual disarmament. Some $1.8 trillion will be invested in clean energy and infrastructure this year, the International Energy Agency said this week. To make sure it’s spent wisely, China’s trade partners need to remove the dubious duties and investigations that threaten to stymie the transition, spend on building up their own capacities, and unleash the vast potential at their fingertips.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. Views do not represent the stand of this publication.

Credit: Bloomberg

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.