The central government has announced a new year gift by promising free foodgrains to all National Food Security Act (NFSA) beneficiaries in the year 2023. This follows a decision to discontinue the PMGKAY (Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana) in December 2022 – a free foodgrain top-up scheme over the NFSA that was initiated in the aftermath of COVID in April 2020.

Before we delve deeper into the economic implications of the announcement, it is perhaps worthy to outline the broad contours of both, the NFSA and PMGKAY.

The NFSA 2013 entitles up to 75 percent of the rural population and 50 percent of the urban population to receive subsidised foodgrains from the Targeted Public Distribution System (TDPS) under two categories of beneficiaries – Antodaya Anna Yojana (AAY) households and Priority Households (PHH). The Act entitles (i) 35 kg of foodgrains per AAY household per month, and (ii) 5 kg of foodgrain per PHH person per month, at a subsidised price of Rs 3/2/1 per kg for rice/wheat/coarse grains, respectively. At an all-India basis, nearly 80 crore persons have been identified and are covered under the NFSA annually.

On the other hand, the PMGKAY was announced during the nationwide lockdown in March 2020, to secure livelihoods in the pandemic by providing additional 5 kgs of free foodgrain per person per month to the NFSA beneficiaries. Initially announced for a period of 3 months (April-June 2020), the scheme ran with successive extensions until December 2022.

Food Subsidy Streamlined

Food subsidies, in India, are typically sticky in nature. The discontinuation of PMGKAY would have been challenging at any point, but the accompanying free provision of foodgrains under the NFSA has made the withdrawal more palatable. It is a deft political move, which carries economic benefits in the near term.

From a fiscal perspective, the cessation of PMGKAY directly saves the government nearly Rs 1.75 lakh crore on annual basis. Over a period of 33 months, the government spent nearly Rs 4 lakh crore on the scheme.

However, the provision of free foodgrains under the NFSA comes at a cost. This cost can be seen as revenues foregone from foodgrains that were sold at subsidised prices so far. At FY23 Budget Estimates (BE) of economic cost (i.e., the total cost of acquisition and distribution borne by Food Corporation of India) of rice and wheat at Rs 3,670/quintal and Rs 2,588/quintal, respectively, we estimate this revenue loss (since the number of beneficiaries and foodgrain allocation remains unchanged) at Rs 14,000 crore for the government on annual basis.

For FY23, taking on board – (1) Annual requirement of foodgrains under NFSA and other welfare schemes (such as PM POSHAN, Wheat Based Nutrition Programme i.e., WBNP etc.), (2) 9 months of allocation under the PMGKAY and (3) Loss of revenue from free foodgrain provision in Q4 FY23, we estimate the total cost of food subsidy at Rs 3.2 lakh crore. This is substantially higher than the BE of Rs 2.1 lakh crore – which had not accounted for the extension of PMGKAY at the time of the Budget announcement.

For FY24, the cessation of PMGKAY is likely to streamline the food subsidy cost to close to Rs 2.1 lakh crore – an incremental saving of approximately Rs 1 lakh crore.

Depletion of Buffer to Ease

Apart from fiscal savings, the decision to bring an end to PMGKAY had become inevitable as buffer stocks of both wheat and rice have depleted considerably in the last one year by ~50 percent and 45 percent, respectively. While stocks of rice remain above minimum buffer norms (1.4x), those of wheat continue to hang precariously close to buffer norms as of December 2022. Recall, the outbreak of the Ukraine-Russia political crisis, an excessive heatwave in April-May-2022 that damaged wheat crop output along with a surge in exports (which was eventually followed by a ban) had led to the dwindling of wheat stocks, as domestic demand remained strong amidst reopening of the economy, festive season spurt and the extension of PMGKAY beyond September 2022 for additional 3 months.

Having said so, the government’s buffer wheat stocks could see a build-up in FY24. While cessation of PMGKAY will help slow the drawdown in stocks, the prospect for replenishment is encouraging from ongoing traction in Rabi sowing. The late withdrawal of the Southwest monsoon, high level of water in reservoirs and a moderate increase in Minimum Support Prices (MSP) for wheat (at 5.5 percent in FY23 against an average of 3.1 percent in the last three years) appear to be supportive factors at play. As of December 23, acreage under Rabi sowing had increased by 4.4 percent compared to the same period last year, with that of wheat (which accounts for nearly half of the Rabi acreage) up by 3.2 percent.

Reprieve for Cereals Inflation

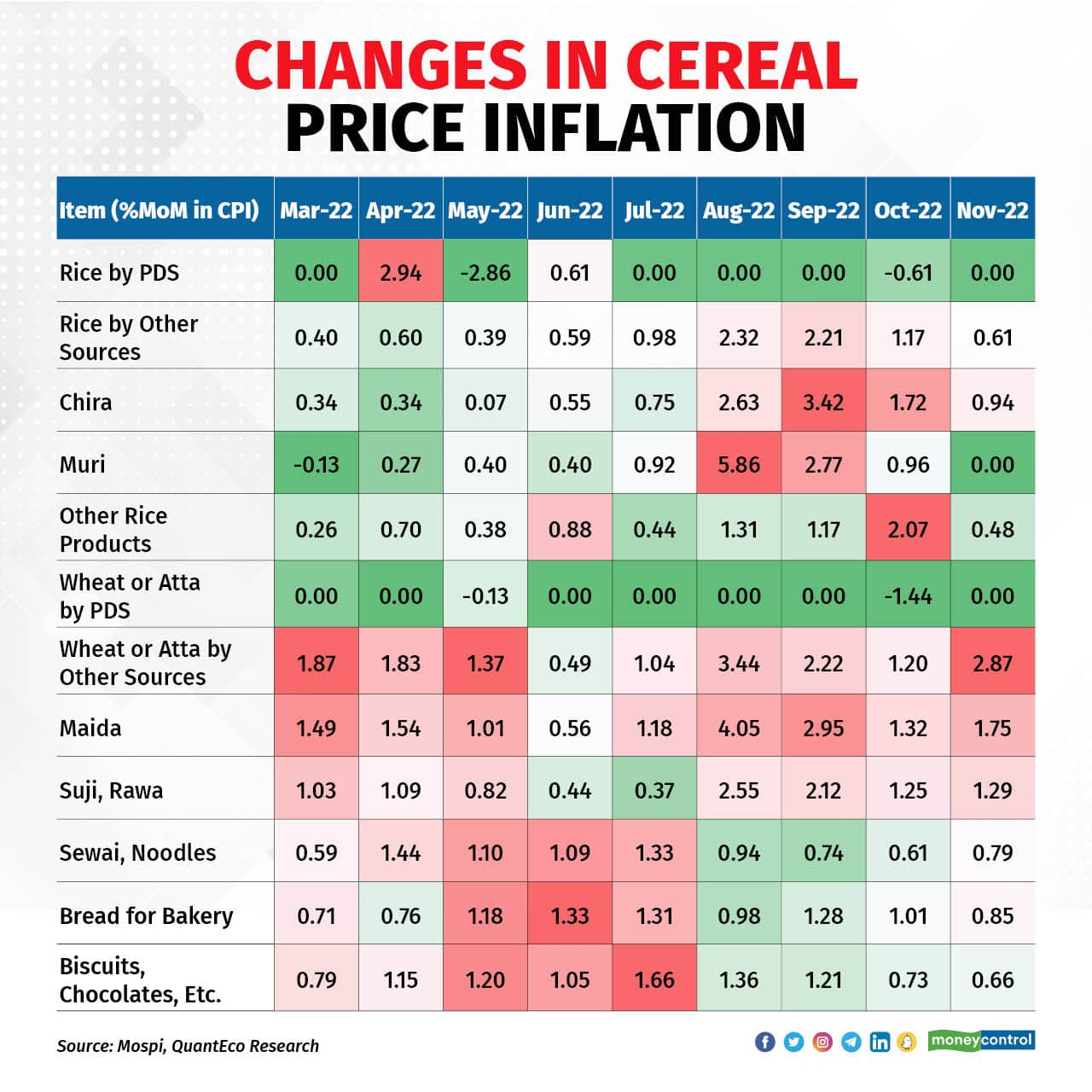

In FY23, following on the heels of wheat price escalation, a lower acreage sown under Kharif rice accompanied by the extension of PMGKAY beyond September 2022, saw retail price pressures getting broad-based for rice and rice derivatives (see chart) as well. This doubled up on cereals inflation, which after averaging a muted 0.6 percent in FY22, rose steadily in FY23 to a decadal high of 12.96 percent YoY as of November 2022. With PMGKAY related offtake of rice and wheat now off the market, some easing in cereals’ inflation can be expected.

Boost Rural Consumption

On the flip side, a reduction in the government’s food subsidy expenditure in FY24 on account of the discontinuation of PMGKAY could somewhat curtail fiscal support to rural consumption. Amidst a slowing global economy, the onus to fuel domestic growth falls disproportionately on domestic demand and more so on rural consumption. This is because levered urban consumption could see some downside, as lending rates undergo a delayed catch-up. In a bid to counter-balance, this should pave way for an enhancement of outlays towards existing rural schemes such as NREGS (National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme), PM-KISAN, PM Awas Yojana – Gramin, PM Gramin Sadak Yojana etc. in the forthcoming 2023-24 Union Budget.

Need an Expiry Date

Looking ahead and indulging in some crystal ball gazing, the termination of free foodgrains in December 2023 i.e., five months ahead of the General Elections could potentially face political challenges. It is likely that the free foodgrains under NFSA could continue well beyond this calendar year.

One pertinent question, that is being raised is whether the government can go back to charging a subsidised price for foodgrains, ever again, In this context, it is important to highlight that since the NFSA was enforced in 2013, the subsidised price of rice, wheat and coarse grains has remained unchanged at Rs 3/2/1 per kg, respectively. In 2013, this subsidised price was decided for a period of three years, with a caveat to revise prices thereafter in line with MSPs, which has never ensued. The lack of revision is even more perturbing given that MSPs for rice and wheat have seen an upward revision of 39 percent and 30 percent, respectively, between FY17 and FY23.

But there is counter reasoning. In a post-COVID world of wider inequalities and economic scarring, can providing free foodgrains work as a safety net for the vulnerable sections of the population? At a cost of less than 10 percent of the total food subsidy bill of the country, the free foodgrain scheme is not unbearable. An enduring increase in tax buoyancy can help finance this for some more years; but it is imperative to discuss, debate and devise the sunset clause well in advance. This is because a free foodgrain policy carries a moral hazard. In a nation of declining LFPR (Labour Force Participation Rate) and one of the lowest LFPR for women globally, free foodgrains can diminish the incentive to work for sustenance.

Every economic policy comes with costs and benefits. A careful weighing of short, medium and long-term benefits versus costs (both economic and social) in the case of free foodgrains policy must determine its longevity.

Yuvika Singhal is Co-head of Research at QuantEco Research. Views are personal, and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.