Philip Mathew

From the general narrative we hear from the mainstream media and the social media messages coming out of the officialdom, we feel that India is on its way to contain the Covid-19 outbreak. After a very successful ‘Janata Curfew’, many celebrated the supposedly gargantuan feat that we have achieved.

The Centre and some states announced various kinds of lockdowns, with the hope of cementing our purported gains. It seems that we have held our fort, against an enemy which decimated the healthcare systems of many high-income countries with finest talent and facilities.

It is indeed true that the central and state governments have played (and continue to play) a very proactive role and have taken the issue head on. From the early stages of the epidemic, the health ministry, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) and the National Institute of Virology (NIV) have brought out regular notifications and protocols for diagnosis. State governments, such as that of Kerala, led by efficient health departments, established helplines and isolation facilities. The healthcare providers were trained in infection prevention and large sections of the public was sensitised about the importance of hygiene practices.

However, is it true that the number of cases in India is limited to less than 400 (which is the official estimate at the time of writing this article)?

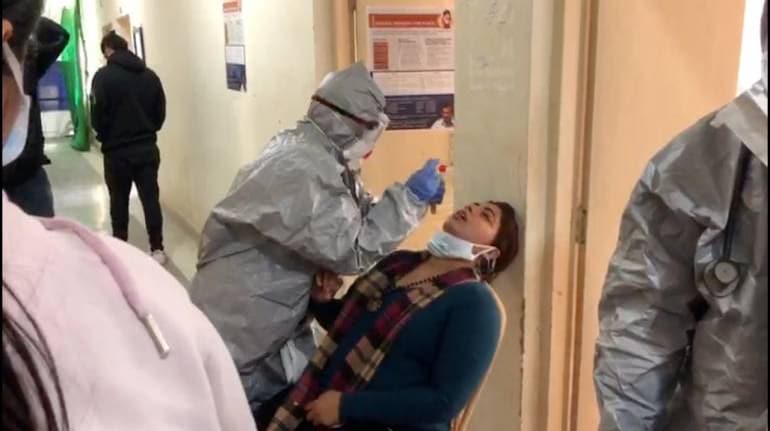

The testing strategy adopted by India has been rather limited in its mandate. Initially, we restricted testing to people with symptoms who are coming from other countries which report local transmission and their primary contacts.

However, we should understand that we were testing symptomatic patients only, for a disease in which majority of the patients are asymptomatic. There are studies showing that more than one in 10 cases of transmission is from patients who do not report any symptoms like cough, body pain or fever.

When we read of all of these facts together, it is reasonable to assume that some patients would have escaped testing and that there may be community transmission of the disease. As of now, India is among countries that has run the least number of tests when we consider the overall population as the denominator. The ICMR has widened the mandate of the testing strategy in the last few days and now it includes hospitalised patients with severe respiratory illness and direct asymptomatic contacts of confirmed cases. However, experts consider this as too little, too late.

Maybe the decision to limit testing in the initial phase of the outbreak was taken because of shortage of primers and positive controls for testing — but as World Health Organization (WHO) Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus put it, “We have a simple message for all countries. Test, test, test”.

The current set of laboratories are testing a few random samples every week to look for community transmission, and that’s grossly insufficient. Though a number of private labs have been roped in for running testing services, we still do not have enough testing facilities which can cover a population of more than 130 crore. We need a nationwide testing strategy for the general public with a much higher sample size to look at community transmission — otherwise we will be groping in the dark. The example of South Korea, which used an extensive testing strategy to control the outbreak, can possibly guide our actions in this regard.

Increasing the capacity for testing is difficult — it needs money, technical expertise and laboratory infrastructure, not to mention the supply of test kits. The easy way out are measures such as ‘social distancing’, which has become the buzzword in the last few days. It essentially means to limit social contacts and gatherings till the time the transmission of infection is controlled. The March 22 ‘Janata Curfew’ is a good example of this, a small albeit necessary step. These steps and drastic measures like lockdowns may indeed slow down the spread of the disease and make sure that the medical facilities are not overwhelmed. However, will it really succeed in India?

Imagine a daily wage earner living in an urban slum in India. In most scenarios, the person may have to share a water source (like public tap or water tanker) with many other households. This is true for many other public amenities such as toilets and community recreation facilities. When the person comes back from work, a single room may be shared by a number of family members who may also be going out for work to different parts of the city. Social distancing may be difficult in a country where we are still struggling with the basic necessities like housing, access to piped drinking water in households and safe sanitation.

The decrease in economic activity as a result of social distancing and lockouts is also going to be high; and, the impact can be massive in countries such as ours which has very poor social security nets. When bulk of our employable population works in the informal sector, it may be catastrophic to do anything which can reduce the overall demand in the economy. Unless we take care of the economic needs and food security of the most vulnerable groups, the social impact of this can eclipse the healthcare impact of the disease itself.

This is never an argument against the efficacy of interventions such as ‘social distancing’ and lockouts, but the question is about its feasibility in the Indian context. We also read about countries which has gone ahead with massive lockouts struggling for an exit strategy — which means that they are afraid to release the pressure in fear of a resurgence in number of cases.

Therefore, we are left with essentially three options — increase the hygiene practices among general public and healthcare professionals, widen the testing to look out for community transmission and ramping up the capacity to deliver effective medical services if this becomes a large outbreak.

Breaking the chain of infection requires clear understanding of where and how the transmission is happening; and a supportive public which is competent enough to look after its hygiene. The exemplary grit shown by the Indian health system in the face of adversity shows that it is possible for us to succeed in this fight. Then again, extraordinary times call for extraordinary measures.

Philip Mathew is Associate Professor of Community Medicine, PIMS & RC, Kerala, a Doctoral Researcher, Karolinska Institutet, Sweden, and a public health consultant for ReAct, an international network on antibiotic resistance. Views are personal.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.