Open AI made ChatGPT 3.5 available to the public without any fuss or mega-launch just over two years ago, on November 30, 2022. Sam Altman has since admitted in interviews that he didn't quite expect it to "get so good". In the months and years following, however, artificial intelligence and its impact on our lives and jobs have taken over entire conclaves, newspaper columns, books, social media posts, threads and reels and many everyday conversations. Is AI coming for your job? What about jobs of the future in the age of AI? What will AI mean for medicine and public health initiatives? How about education? Travel? Music (remember Ludwig van Beethoven's last symphony that was completed using AI?)? Design... what about ethical and responsible AI and AI safety? Do we need international regulation? Do we need to pause development in AI till we know more? Equally, podcasts, newspaper columns, expert articles have called attention to how AI, though potentially very disruptive, is hardly the first disruptive tech in living memory. The world wide web, dot-com companies, mobile phones, smartphones, wearables, social media, video calling, instant deliveries - things that we take for granted - are all relatively new. Lately, discussions on AI have also looked to the past, to how previous generations dealt with disruptive technologies that had huge potential impacts for human endeavours and earnings. The word Luddite - used as a pejorative for much of the late-20th and early-21st century - has been revisited in a book and in podcasts to see what they were really protesting: the technology upgrade or the resulting job losses.

Over at the Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad's (IIM-A's) Centre for Digital Transformation, Prof Pankaj Setia has been adding a few more complications to this conversation: Instead of talking about jobs that will be lost as AI gets better, cheaper, he asks what if jobs are no longer necessary in the age of AI? What if we leave machines to do what they do better than humans, and guarantee everyone a basic income and a minimum standard of living? What would we do with our time and our talents then, once we are offered "extreme freedom from the computations of survival"? What would we do with (what Prof Setia calls) computational freedom of the kind that is currently only available to some kids who are expected to devote their time and resources to learning more and varied things?

Prof Setia has been thinking about human purpose in the light of newer, more advanced digital transformations for upwards of 24 years, much before the ChatGPT 3.5 release. He says there's no need to fear AI, though it should kickstart conversations around human purpose and the reason why we work jobs. To this end, the professor has been running a thought experiment with his students at IIM-A, asking if they would take Rs 5 crore or Rs 10 crore today on one condition: "you will never do what you are doing" right now. "No one says no," he says. Prof Setia says this computational freedom from the responsibility of making a living is a potential upside of technologies like AI that free humans of the drudgery of survival.

A phone conversation with Prof Setia in December 2024 quickly turned philosophical, as he spoke about his new book 'Purpose', the intersection of technology and human purpose, why digital transformation is critical to human survival, why Gen Z seem to have more time than previous generations to think about their purpose on earth and why we need to revisit purpose at an individual, societal and organizational level when faced with new technology that can potentially change how we live and work. Excerpts from the interview:

A couple of years ago when ChatGPT released its 3.5 version, suddenly there were all these conversations around whether they are going to put people out of jobs. In the book you explain that a good manager looks at what the new technological abilities are and reorganizes the work in a way that it does not become a zero-sum game, it's not humans versus machines. Can you unpack that a little bit?Yes, it's true. I give this example: In the US, there's this actual thing that happened. Hollywood writers went on a strike. I'm pretty sure you read about it. The entertainment industry was crippled. Why? Because they did not find the way the organization of work was conceptualized and done by the studios to be apt. There is a work rhythm.

In the book I talk about two things. There is a constitution of work, which is how the work will be done, set of activities, what will be the interdependencies and such. You have to create and structure work - who are all the people, who will do what activities, etcetera, etcetera. That's technical in nature.

But the other thing is the rhythm at work. There is certainly a rhythm. And the rhythm is not something that technology captures. Rhythm is a human element mostly. It comes from how individuals work, how they come together to perform right. And you can see it in a dance performance very clearly. You can also see it in how driving happens, and you can compare it in different countries. If you go to a western country, driving rhythm is very different from driving in Delhi, which might be very different from driving in a smaller tier-3 city, for example. And those rhythms are very different. They are all working. Any driver is doing the work, he or she is driving a vehicle from one point to another. They might be doing it professionally or they might be doing it for personal reasons, but regardless, they are driving, doing the work of a driver. And that rhythm is very different. You can see it to be different in different places in the world.

The point is that same rhythm is also existent within any organization. And the moment technologies come in, they have the potential to transform the rhythms, so managers have to be cautious about the changes in rhythm. Not many managers are able to consider or think about that. They are very clear that ChatGPT will do this work or that, and we save these people (layoffs or savings in terms of human resources). That's not how great organizations are created.

Great organizations are very rhythmic places where they do work in a certain fashion, certain ways, and there is an individual rhythm in-built into it and there is an organizational rhythm. And if you see great organizations, SAS comes to mind, they would never let their people go. They would never say these are the people who are the best employers. They say we will support it in the time of downturns, even if we don't need you. So the point is there is a short-term temptation to let people go and to hire and fire. I would call it a lazy manager, who is not willing to spend the kind of energy that is required to restructure in a manner that they should be doing.

To stay with this AI example, there's some conversation around stated purpose versus actual purpose. The profit motivation or the motivation to be the first to do something can be quite high, and AI seems to divide people down the middle - there are people who are extremely gung-ho about its possibilities and how it could coexist with humans on the one hand. On the other hand, we have people who think that AI will evolve to a place where it will eliminate humanity or that humanity will no longer be necessary for further digital transformations to happen. Where do you stand on that divide, and where does purpose fit into that space for you?Purpose is a human element, number one... I am all for AI, we should get AI. Many times, students ask this question - in India, but also in US when I was teaching there - how I think about autonomous cars. People are worried that this (technology) would lead to very large-scale changes in our lives. It might hurt; the kind of things you are saying. They might replace everything on the planet. It can be huge. But then I tell them that AI is a radical technology, I agree. But it's not the first radical technology on earth. In fact, I think the more radical technology might have been knife. When knife wasn't there, it would have been very scary to bring such a technology into the house that can be used to kill. In fact, it is used even today for negative purposes. You can still read to read stories in the newspapers about people get hurt. But there is no kitchen today that you can tell me that doesn't have a knife.

The scale perhaps of this seems different; a very small section of the population seems to really understands AI, whereas the implications of it would be for everybody, whether or not they understand...True. I think you've answered the question. We don't have to give up a great potential technology just because it looks daunting. And I'll also tell you it's not very daunting. There are a lot of people who have, I think, an advantage or who have a way to just create a genie out of a thing... It's not very daunting to understand. It has great potential. It has a great impact. It is very powerful, but that does not mean that we got to fear it. I think it's a matter of "how do we ride the horse?" How do we ride this great beast so that it works in our favour? That's the only thing to think about. That's the only thing in my mind to worry about. That's the only thing I fret about. I don't worry about technology. In fact, I am very excited that we have a great powerful thing.

I think I mentioned it in the book, the last time I was this excited was about nuclear energy and I was a student at that time. And that excitement did not last long because I realized people used it for very nefarious purposes. For destruction. And I think that's the only thing I fear, and that's the reason I actually wrote this book. I really fear that there is a great potential, and we should be very careful and spend a lot of time to understand how to harness this power. It is more transformative than anything we've heard about so far. It has a great potential, but it requires a lot of purpose-driven transformation to be able to pull it off. That's what my conclusion was; that if only we can do a purposeful transformation of our lives, organizations and societies, that's the only way we are going to pull it off. Otherwise, disasters have happened before, and I really fear that should not happen.

How is purpose different from a resolution or the vision and mission statement that organizations typically put out on their website or in pitch decks and press releases, etcetera? Is there a continuation between purpose and vision/mission statement or is it a completely different thing?Couple of things: One, I talk largely in the context of digital transformation (in the book), and digital technologies sometimes even question and challenge your vision and mission in the sense that a lot of companies are transforming themselves in ways they would not have thought about earlier, or if they are not changing, at least they are rethinking on who or what they are. And the idea of purpose, as I think about it, is that it's a force that is latent. So vision can be created from a purpose, but purpose is something that is exogenous, it comes from outside. I discuss in the book, especially when we talk about existential purpose, I write that there's a latent drive amongst all of us which is neuro-scientifically driven. We are driven through our brain circuits and through an evolutionary process to act and achieve certain goals, and organization is a way that helps us do so.

If one understands this sort of trinity of individual, organization and technology, the purpose manifests at the intersection of the three. While you can say a vision may be fulfilling a certain purpose, purpose I see as a latent force which is very strong in nature. And I say that carefully because if you see in the last 20 years, the kind of growth you have seen in technologies, be it the Googles of the world or many other technologies that have become so widespread, I think there are very few examples in history that have grown so rapidly as digital technologies have grown in the last 20 years.

Purpose is that force, in my mind, that is latent and hidden and goes even beyond organization because it fits at the intersection of individual, technology and organization.

If purpose is a latent force that at some level our brains are wired to follow, then where is the need really to think so much about purpose - whether it is in your personal life or as a business?Excellent question. So that's why I bring it into three types of purposes. One is what do you do when you are thinking digital transformation. The first purpose, what I call the instrumental purpose, helps you think about what do you do to transform or what do you do when you transform. And that's one type of purpose. Then I talk about the operational purpose: how do you do it? There is certainly a change in what you are doing and how you are doing it. Now, the (third:) existential purpose, which is what grounds us, whether there is a systemic change. See the reason we were doing things, the whys, many of the whys are also becoming less required. For example, a person who is running a house... if they were spending their energies on doing things the way they did (because often that was the only way they could be accomplished). Today, even with (house) work, they are able to do a lot of other things. Now the purpose, if you think from that individual's perspective, has transformed. Their why would have also changed. It's not like they are doing less in terms of managing house. They are transforming their purpose of life differently, right?

So again, just to summarize the answer, the what and how have clearly changed and why are people doing things, their existential purpose, a lot of that is being thought through deeply by the current generations. They think more deeply because they are able to think more deeply. They may have more resources to do so. They may have more time to do so, they just have an environment where such things are possible when many of the previous generation of people 100 years ago may never have even had time to think that deeply about existential purpose. Those are the kind of things that are making this discovery of purpose also a little bit more rampant and more methodical for sure, if not more systematized.

You write in one place in the book that humans need digital transformations, to evolve into the next stage of being. And then once you have digital transformation, you need to sort of realign everything else in your life to fit that. How do you see this? Is it an unending cycle?You are raising very, very crucial questions and the reason I highlight that because that's what the debate is. Across many places in US and some of the developed advanced economies, they are talking basic income, they are saying humans cannot compete with technology, so let's give them the money.

Even in India, there has been debate on how many hours people should work and things of that nature. It is tricky. It is tricky because while technology has always come as an external force to our lives, we haven't ever been able to manage it seamlessly. But what is different in this case is the time that we have to adjust and manage is much shorter now than before. The kind of advances that are happening at the pace at which they are happening, it's a little faster than what a human mind has traditionally been used to, to organize things.

Now, if you say that we are adjusting our purpose idly, no one should have to. Ideally the technology serves the human purpose. In fact, the whole idea of this book and the reason I wrote it was because I see that technology in humans may potentially get into - it is probably not right to probably use that word, but a - sort of a competition which is happening in many places.

To take the example of chess, when Deep Blue beat the chess champion, Garry Kasparov (in 1997), the idea was that technologies are getting better at doing things much better than humans are. So, it is in that sense that I said humans may not have the capabilities to match up with advanced technologies. Now, if you see what Garry Kasparov did afterwards, he ran a freestyle tournament where he said anybody can participate: a person, a computer or a combination. And invariably the winning entity now is the team of human and computer, neither computer nor human.

The idea is how do you create or organize the world differently, where you can bring these things in in a manner that human purpose continues to dominate to the extent it should. I categorize it, because not every human is following a purpose that is in line with what I would call the evolutionary purpose or the existential purpose. If you are hurting somewhere - that's where the tension comes.

Some places, technology just does it better and has the potential to enhance human purpose at scale when individuals may not be able to. So that's the dilemma there. And if humans have to adjust, to me, it is a matter of us not understanding the interrelationship between the two to the degree or to the extent that it should be. And this requires questioning and challenging many things. There are different aspects one has to think about: how do we question and challenge this relationship which seems to be more of a competition in many places. And that's where I think your comment is coming (from) is if humans have to adjust to the purposes (as) new technologies come in, etcetera, it seems that they are pushing us around and such. But that's not how it should be if we organize in a manner where the two are synchronized.

Maybe it's a nostalgic idea, but shouldn't human purpose be unchanging? Irrespective of technological or any other breakthroughs?I am glad you are asking that. There are parts of purpose that have always remained the same. If you see in our day-to-day activities, there are certain things that we have continued to pursue since (for)ever. There are certain things which have remained the same. But now, more and more, people are pursuing a purpose which is different from what they may have imagined even 100 years ago.

The idea of, let's say, adventure. Or so many people plugging into digital networks, trying to get better at skills and personalities... (Some people could) say everything that is happening online is not good. (But) a lot of people now learn online. They listen to others online. They interact with others online. It has heightened to a level where people are getting into personality tests, skills tests, trying to be a better version of themselves. It's not that people did not meditate before or people did not read before. But it is happening in manners that have transformed the way we think about ourselves.

There are some parts of our purpose that have continuously remained the same and some that have changed. Let me give you an example. Say you are into fitness; let's just take that paradigm. People might have always worried about fitness, but the way they are able to stay fit today because of the advances in technology, that is something they would have never thought about. It's not like people did not pursue fitness before, but the way they are doing it systematically, with numbers given to you in real time, for example - it opens up a whole new set of avenues. So while the broader purpose will continue to be fitness, the way they are achieving it has changed tremendously. And that's the idea. You know you are discovering the purpose also in some manners, if you think about that.

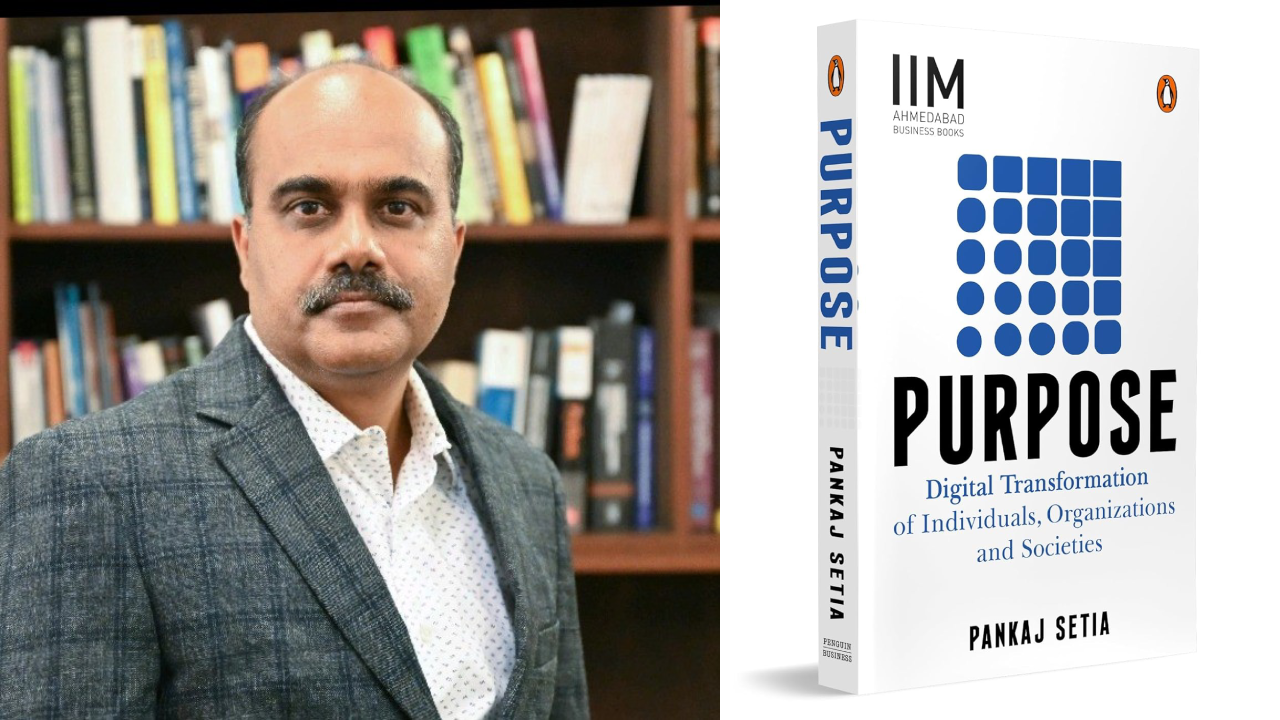

IIMA Professor Pankaj Setia is the author of Purpose: Digital Transformation of Individuals, Organizations and Societies. (Images via LinkedIn and Penguin Random House)The book talks about digital advances, and of course people are often excited about them, especially with artificial intelligence and artificial general intelligence, which seems to be the next big thing that people are looking forward to. But really what we shouldn't lose sight of is that larger purpose of human existence, which may not always align with the immediate organizational or personal purpose. Is that right? Are we sort of zooming out a bit?

IIMA Professor Pankaj Setia is the author of Purpose: Digital Transformation of Individuals, Organizations and Societies. (Images via LinkedIn and Penguin Random House)The book talks about digital advances, and of course people are often excited about them, especially with artificial intelligence and artificial general intelligence, which seems to be the next big thing that people are looking forward to. But really what we shouldn't lose sight of is that larger purpose of human existence, which may not always align with the immediate organizational or personal purpose. Is that right? Are we sort of zooming out a bit?Yes, you are right. See you can analyze this thing as like I said there is a three-way interaction or three-way conflict between three entities. One is organization, the other is individual, and the third is technology. And these three pillars are influencing each other in manners that are sometimes very radical if technology is putting individuals out of job or hurting them or leading them. And that's why people are coming up with these organizations are talking about things like basic income. They are talking about securities for individual because they know that their current organizations are not able to champion it the way they are.

The organization itself - the way most of the organization happens today - is a product of the industrial-era development. This was largely the factory mindset which has evolved over many generations. The organization happens in a certain way in the economic system, and that economic system and the organization is being challenged by the new technology. There are fewer people are doing work equivalent to or that would have been done by hundreds of people before, a technology is able to do the same. Multiple examples of this, even in the legal area or many other places, where technology is much more efficient. I mean Open AIs of the world and others have given you the examples of how one technology can do a lot of work may be good or bad or there may not be 100% there yet. They are almost getting to a place where they can do a lot of work replacing or equivalent to a lot of people. Now that is what raises the question that what does it mean... For individuals and organizations, it is a challenge to rethink what are they doing? Whether we are doing the purpose with which we are working is indeed the thing that we should be working for.

I will give you one example: I often say this in my class. I say if you go out of this room and you walk on the road for 10 minutes and if I offer anyone who comes my way, then I will give you Rs 5 crore or 10 crore, whatever money I will give you 5,00,00,000 or 10,00,00,000 and I will ask you, you will never do what you are doing, how many of the people will say no to me? Not many. It's not their purpose. They are working for a reason, not for a purpose. And the moment I give them the 5 cr or 10 cr, their reason is done for life. And that's freaky, right? I mean, it's not an ideal world to begin with in a lot of technologies are questioning and challenging us on such deep aspects and we need to think: why is it that people are working? Is it really that it's their life's purpose? So the questions that are being asked by technology are very fundamental - they are very fundamental, they are very basic and it is at that level we have to find the solutions as well.

If we push that a bit further and challenge that a little bit in terms of the purpose of our life - and you've also mentioned the existential purpose of people, of individuals, of companies, of other entities earlier in this conversation- say, the purpose of life is not work. But there is some sort of larger purpose? Or is it mostly self-serving?It's sort of a long discussion, at least in this book, what my answer is computational freedom. And if you read, I think it's chapter 14, where I talk about that idea that every individual or any individual ever (who) has pursued a purpose is to be computationally free. And what that means is that at any point in time, if I don't go and work or if I do not do something in my life, I would be stressed out, right? I need to feed my family and things like that. The moment I can do something which frees me from that stress, I would choose to do so. For many people does job, right? And you can think about it in very many different ways that all are human being pursues throughout his or her life is to be free from you know these computations. Computations that are usually stressful or that would become stressful if they were not to do or act in a certain manner.

Jobs and other things are just examples of that. And that is where my thought experiment of giving 5,00,00,000, 10,00,00,000 to anybody who comes out, tells you: that the moment you give that (money), they achieve extreme freedom from computations about survival. Human beings compute differently from others in the animal kingdom. Most other animals and species are thinking survival most of the time, unless they are pets and others. They are all thinking survival. Whether it's a lion trying to get a hunt by chasing a deer or a deer trying to escape from a lion. I use that example in the book and all of them, they are thinking about survival. Human beings like to think about complex mathematics and write papers and research, and how do we create satellites to go to moon, for example. They are very complex, arcane philosophical issues. I mean, we are right now discussing this idea of existence. I am not sure many in the animal kingdom - and I say that with a little humility - but I don't know how many of the animals have the freedom to think that much.

Neuro-scientifically also, their brains - their neural networks are not as dense as humans - they are different. Humans seek freedom, computational freedom, to be able to think of different things, right? So if work is the level of (evaluating) things, we don't let our children, for example, go and work - we give another freedom to think. They are learning math, they are learning physics, they are doing arts, they are music and everything else. Why? Because we don't want them to be thinking about work. We don't want to constrain their thinking. We want them to be computationally free, and yet guide them. So the point is, at least from digital transformation perspective or since we are studying the idea of advent of these large digital technologies, many of these technologies come in because the key value they bring is that they free the human minds from computations.

To go back to your lion and deer example in the book, you complicate this further by saying that there is a human who is in a perfectly safe space and has an option to shoot the lion. Can you explain what you were hoping to do by complicating this situation, by putting a human in the mix?I ask my students this question many times, too. And most often, they say no (they won't shoot the lion). And the answer (reason) is it's a natural cycle. In the book (example), it's a zero-sum game, the idea that only one will survive has been entrenched and accepted by us.

It's a natural cycle that we so value that we sometimes forget to think that that natural cycle can be intervened with. Now many times, people who come in my class are CEOs and CIOs and leaders. And I tell them that no society has ever grown or progressed by not intervening with nature. We may not have done it right. That's a different issue. We do a bad job of it, but humans are the only species on this planet who have the ability to make the world "a better place". We are the only ones who change the world, or at least to the level that the evidence indicates on this planet. We are the ones who have changed the planet the most. So we have to think about everything and not close our eyes by saying it is a natural cycle, and it's not a big thing to address if you think about this problem fundamentally. But the central tenet, the reason I complicate this thing is, to make people think that there are many such issues in the world which indicate a zero-sum game or a fixed reality which cannot be challenged. And if you think digital technologies, they often go after those things.

Pankaj Setia (Image via Instagram)What does the Center for Digital Transformation do? And you know, what does it mean to teach information systems?

Pankaj Setia (Image via Instagram)What does the Center for Digital Transformation do? And you know, what does it mean to teach information systems?Centre for Digital Transformation, we started with the goal to pursue research and do some analysis to understand how digital transformation manifests. This book also comes largely from support from the center. We have a couple of people on our Advisory Board and a council that we have created. It was meant to study a lot of issues like responsible AI, how can we build technologies that are responsible? We did a large-scale study. We sometimes work with companies, and we did a large-scale survey of how technology is in the retail sector. How does it influence consumers, for example? We studied the inclusion aspect. So couple of people who are associated; Nandan (Nilekani) is one person who is on the board; there are a couple of academics from US, the dean of Wisconsin Madison School of Business, the Dean of Carnegie Mellon Science School of Public Policy Krishnan, and you know Aditya Puri from HDFC. So couple of people are on the council and we try and study largely topics that would fall in the broad domain of digital transformation. What you read in the book is a summary of what I have thought about, study, observed, worked on, etcetera. But there are a lot of different smaller studies that go on which lead us to conclude or assess digital transformation in different domain.

And when was the centre founded?It was in 2000. I actually moved back from US after 17 years. I had gone there for my PhD and I worked there for many years and I moved back in 2000 and it's at that time that I may was looking to set up the centre. So I was the initial founding chair for that center.

2000 is very early in the digital transformation space. Were your conversations very different then compared with now?Because I was coming from us, US had already taken a lead in some spaces. So I knew what was ahead and some of it is unfolding I think. And I&I am actually very pleased to see that things are unfolding after what we have learnt from us on DCS of the world are some examples of things that are happening, opening up the public commerce or open commerce, for example. So you are right, some of the things have transformed very radically, especially during COVID time when we moved back. Things have sort of transformed much since then. But you are right, things have just progressed further and I still think its early days. There are lot more transformation is ahead of us. I just hope that it is in in line with what our broader purposes.

And if you could define your broader purpose, that would be great.It's the same as I wrote in the book: we would like everybody to be computationally free. And that's the only purpose that I think we have to pursue for everyone. If you think about the idea of freedom that I talk about in the book - the computational freedom - people should not have to be worried or thinking about things that create negative emotions inside of them. That's the only broader purpose. Now I know that's a very global goal and very broad goal, but that's the goal that we have to pursue. And within that ambit, whatever it is that we can do.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.