Earlier this week, on August 15, the People's Bank of China (PBoC) sent ripples through global financial markets after it cut interest rates by 10 basis points.

The Chinese central bank's decision to do so comes even as central banks around the world are tightening monetary policy to fight high inflation. While this would hurt growth, central banks believe it is more important to bring down inflation – which is over 40-year highs in some cases – as it is detrimental to growth in the medium- to long-term.

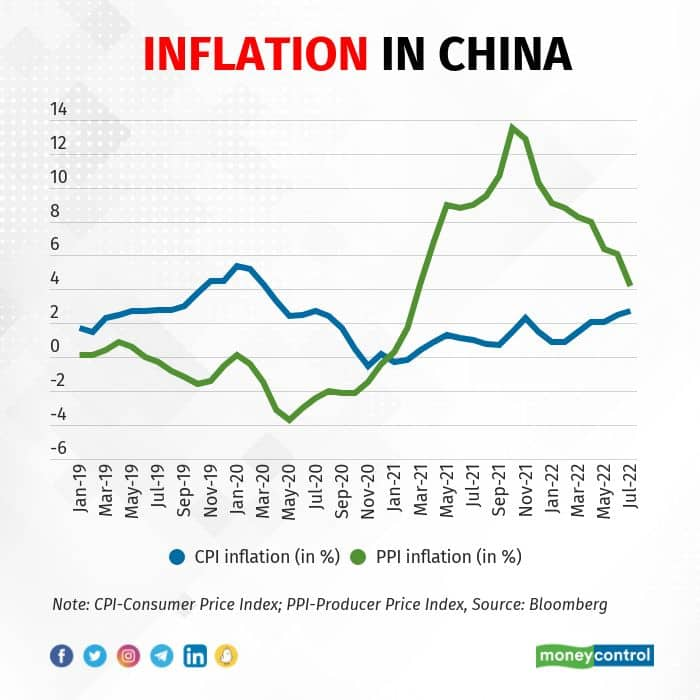

China, however, is currently not battling high inflation; at least, not the sort other large countries are witnessing.

While Producer Price Index (PPI) inflation has cooled down from the double-digit territory it was in late 2021, consumer inflation in July rose to 2.7 percent – the joint-highest since April 2020. As such, the PBoC is not in a position to ignore inflation altogether.

The growth situation, then, has to be rather dire for the PBoC to cut rates even as inflation concerns remain. And it is.

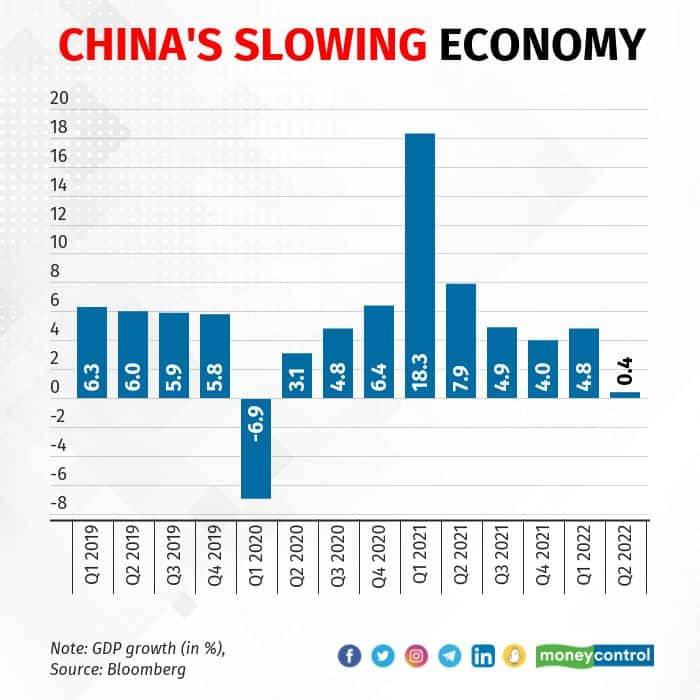

Last month's data showed China's GDP expanded a mere 0.4 percent year on year (YoY) in April-June – the slowest since the economy contracted by 6.9 percent in the first quarter of 2020 when it was confronted with the worst of the Coronavirus pandemic.

More recently, the PBoC's August 15 rate cut came immediately after data showed China's industrial growth came in below expectations at 3.8 percent in July, with growth in retail sales also missing forecasts.

The Chinese central bank is not the only one to have taken notice of the weak economic data. On August 18, Nomura cut its GDP growth forecast for China for 2022 by 50 basis points to 2.8 percent and by 40 basis points to 5.1 percent for 2023.

"China's post-Omicron rebound has fizzled out and the prospects for near-term growth are poor," Julian Evans-Pritchard, senior China economist at Capital Economics, said in a note on August 18.

"Virus outbreaks are happening with increasing frequency. The housing market remains in a downward spiral. And exports look set to drop back before long. To make matters worse, credit growth has so far been unresponsive to policy easing. More support is on its way but it will probably be too late, too little to prevent output from stagnating this year," Evans-Pritchard added.

China's zero-COVID policy has forced several parts of the country to shut down. As per some estimates, nearly two dozen cities – accounting for almost 10 percent of the GDP – are in the midst of some form of a lockdown.

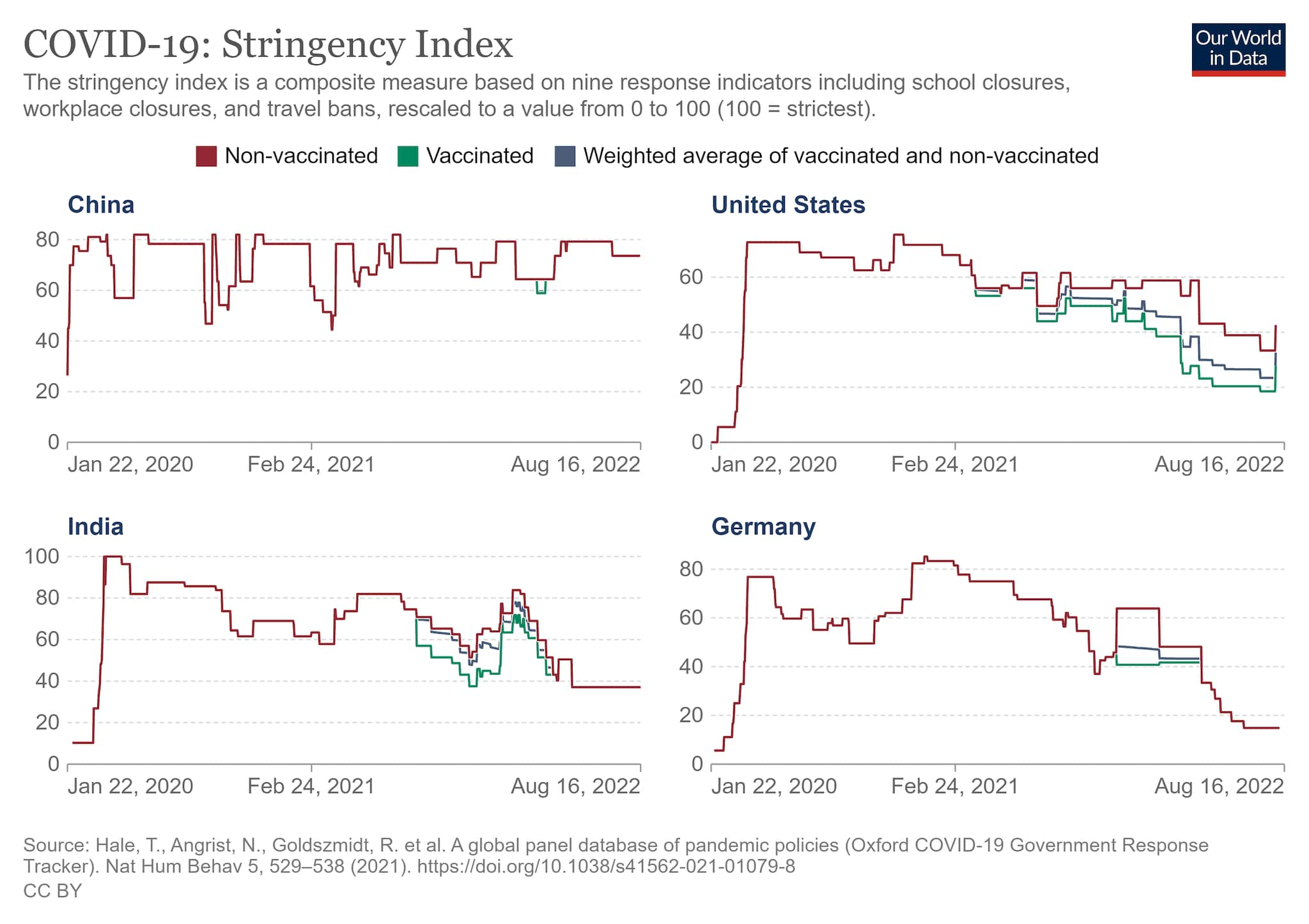

Just how restrictive are China's lockdowns? According to the University of Oxford's Government Response Tracker, the stringency index for China, as on August 15, was 73.61.

The stringency index measures how strict a country's policies on people's movement are. It measures this on a scale of 1 to 100, in increasing order of stringency. While China measured in at 73.61 in mid-August, irrespective of the vaccination status of a person, the US was at 32.63 as on August 2, India at 37.04 as on August 16, and Germany at 14.81 on August 8.

To put this in perspective, the last time restrictions on people's movement were so stringent in India was at the peak of the Omicron variant-led third wave in early 2022.

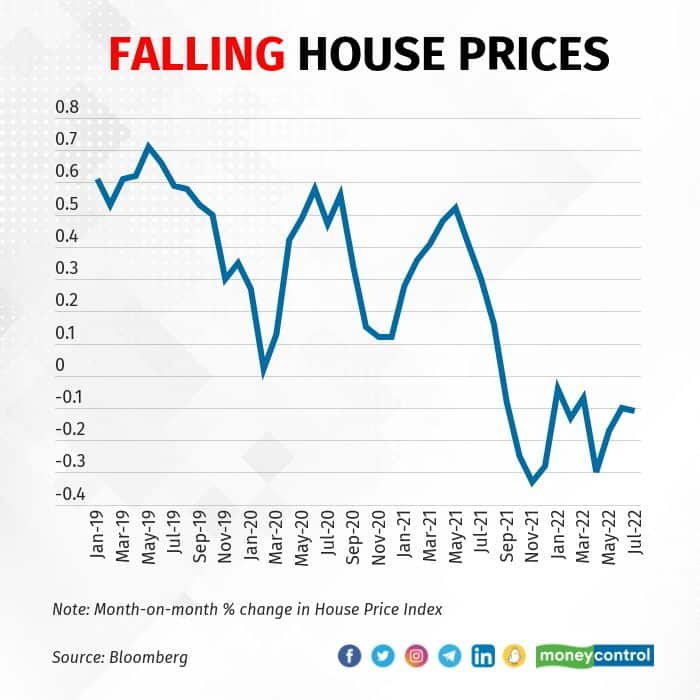

Also making matters worse for the Chinese economy is the unravelling of the housing market, with July being the 11th consecutive month in which home prices fell on a month-on-month basis.

The debt-laden Chinese real-estate sector has been a problem for some time now. However, citizens have now taken matters into their own hands by refusing to repay home loans for houses yet to be completed. According to the South China Morning Post, the 'mortgage boycott movement' is now active in 320 real-estate projects across 100 cities.

Such has been the ferocity of the movement that, late last month, the Politburo announced that local governments must ensure delivery of housing projects. Further, as per a July 27 Financial Times report, the PBoC plans to issue low-interest loans of 200 billion yuan, to begin with, to enable state-owned banks to help the flailing realty sector, and therefore, the economy.

That importance of a rapidly-growing China for the Asian and global economies cannot be overstated. In the July update to its World Economic Outlook report, the International Monetary Fund had downgraded its global growth forecast for 2022 by 40 basis points to 3.2 percent, with the slowdown in China being one of the key reasons.

According to Nomura, "the downcycle is just starting".

"China's credit impulse leads Asia's export cycle. It is pointing to continued slowdown, negative growth next year, and a trough only around mid-2023," Nomura economists said in a note on August 17.

"...going forward, the weakness is likely to spread as final demand slows across the advanced economies. The downcycle is just starting."

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.