Bad debts are on the wane, in fact, the pain point for lenders is healing up faster than ever thought.

The latest Financial Stability Report (FSR) shows a massive drop in both gross and net none-performing assets (NPAs) of commercial banks. But, how did this happen?

First, let’s look at the improvement in asset quality.

As per the June 27 FSR, the gross non-performing assets (GNPA) ratio of Indian banks continued to decline to a multi-year low of 3.2 percent in September 2023, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) said in the FSR on December 28. The net non-performing assets (NNPA) ratio declined to 0.8 percent, the report said.

This is certainly a piece of good news for banks. Their books are much cleaner now. Also, this is a great news for bank depositors and shareholders. Better asset quality means stronger financial institutions and better stability. For investors, this brings the prospects of better returns if its accompanied by growth.

Wonder how did this happen? It is important to understand the magic formula behind such a big reduction in NPA.

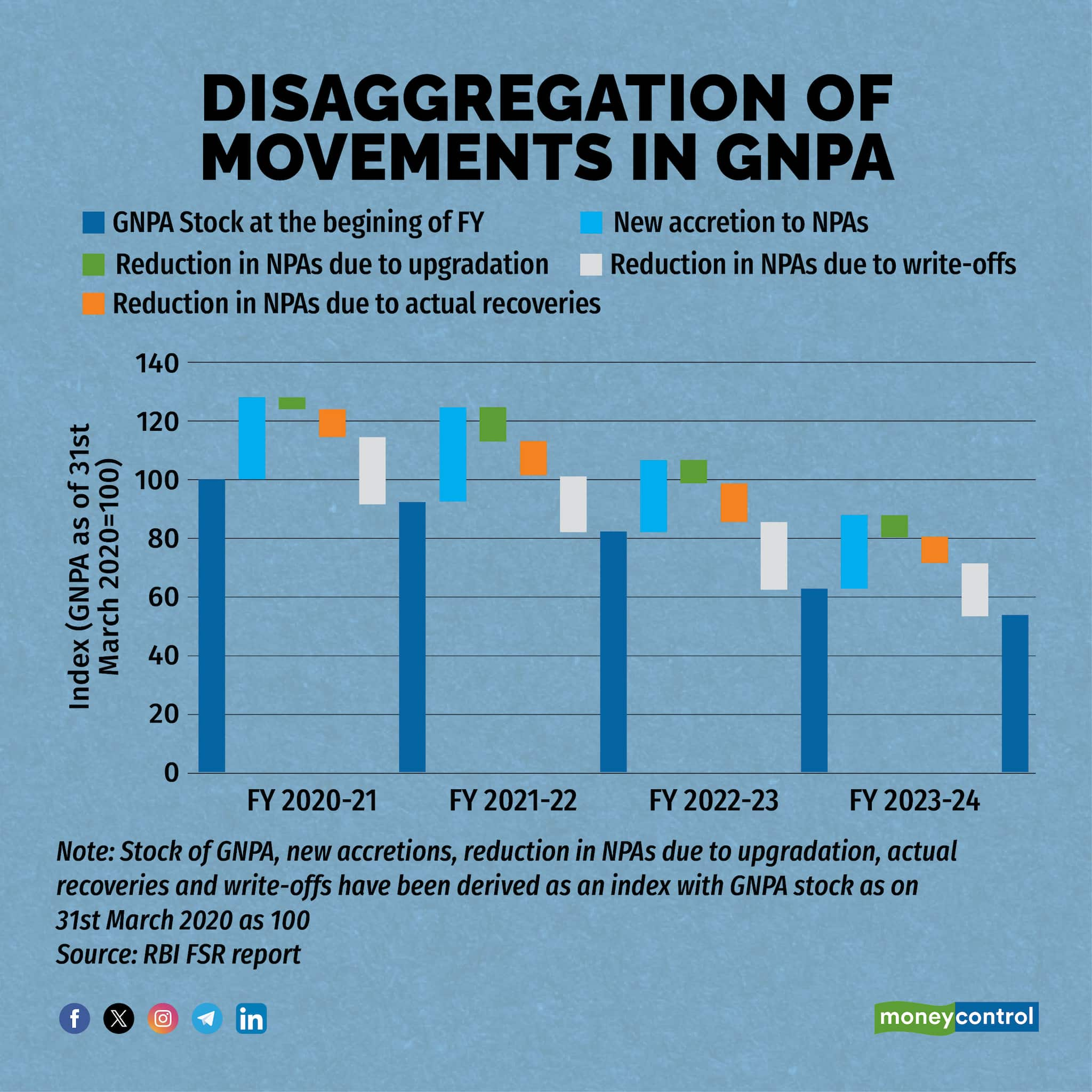

There are two factors that have been played out - fall in fresh bad loans and massive loan write offs. Of these two, huge loan write-offs, particularly in corporate loans, has played a key role.

“The half-yearly slippage ratio decreased across bank groups. Though the chunk of write-offs declined during the year, the write-off ratio remained almost at the same level as a year ago, due to reduction in GNPA stock,” the FSR said.

Loan write-offs

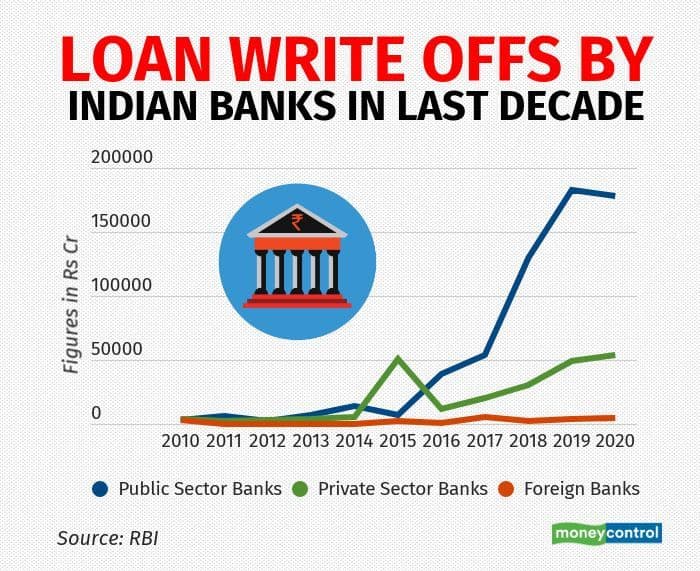

A big chunk of the corporate loans have been written off in the last decade as part of the cleaning up exercise of Indian banks. Majority of such loans belong to state-run banks. The government had last December informed the Lok Sabha that all Scheduled Commercial Banks wrote off nearly Rs 10.6 lakh crore in the last five years, out of which nearly 50 percent belong to large industrial houses.

The government also said that nearly 2,300 borrowers, each having a loan amount of Rs 5 crore or more, willfully defaulted around Rs 2 lakh crore.

Public sector banks have written off around Rs 10.42 lakh crore and recovered an aggregate amount of Rs 1.61 lakh crore from that between 2014-15 and 2022-23, Minister of State for Finance Dr Bhagwat Karad had said in a written response, quoting Reserve Bank of India (RBI) data in December 2023.

A look into the figures unfold that the state-run lenders, which had skidded into their worst nightmare of mounting bad debt around 2018, could not recover even Re 1 as against Rs 5 written off in the nine fiscal years starting 2014-15.

Loan write-offs happen when banks no longer feel hopeful of recovering money though usual recovery channels and want to get rid of the burden taking the loan off the book. But this comes at a cost. Every loan written off needs to be provided fully by the banks, meaning that the bank needs to set aside money equal to the amount being written off. This impacts their profitability.

But this isn’t a development of last five years. Loan write-offs have been happening in a big way over the last 10 years, which is the primary reason why the banks are now showing a lower quantum of bad loans is the large-scale write-offs in the last one decade or so.

AQR implementation—a big turning point

Particularly after the RBI introduced the framework for early identification of stressed assets and implemented the asset quality (AQR) review process under former governor Raghuram Rajan in 2015, the banks were forced to declare all bad loans and make provisions. As a result, the Gross NPAs of banks surged from about Rs 2 lakh crore all the way to around Rs 9 lakh crore in three to four years.

What followed was substantial write-offs in loans. In the next five financial years till 2022-23, the Indian banks wrote off over Rs 10 lakh crore of unpaid loans. According to the RBI, banks have written off Rs 15,31,453 crore since FY2012-13.

A loan that is written off is moved from the books of banks, and hence the books look much cleaner with lower NPA levels. But the fact is that these loans remain in the financial system and become a cause for concern till the time it gets resolved. A technical write-off still means banks can recover money they can. But data suggests that such recovery is typically only a small fraction of the total money at stake - around 18-20 percent of the total.

To be sure, the lower addition of fresh NPAs is a good sign. This shows somehow borrowers are able to pay back their dues reflecting well on the economic recovery on the ground. But, this may not be the main reason for the sharp improvement in bad loan scenario.

“Overall, the sustained reduction in the GNPA ratio since March 2020 has been primarily due to a persistent fall in new NPA accretions and increased write-offs,” said the report.

If the economic recovery stays on track, banks will see further moderation in their bad loans going ahead. Rating agency Icra’s Vice-President Sachin Sachdeva recently said the agency expects a further moderation in the gross non-performing assets ratio for the banking system at 2.2 percent by March 2025 from 3 percent likely in March 2024. "This will be the lowest level since September 2011," he said.

Further, the unsecured retail advances and loans to non-bank finance companies too will slow down in FY25, leading to a dip in the overall non-food credit growth in the system, the agency said. The RBI's curbs on unsecured lending by way of increasing the risk weights in November have led to a reduction in the incremental disbursements of such loans to over 23 percent from 29.4 percent earlier, it pointed out.

Who pays for loan write-offs?

A more important question probably is who pays the price of massive loan write-offs finally? Corporates who draw large loans get away in most cases of loan write-offs after defaulting thousands of crores in loans. Remember the old adage: "If you owe the bank $100, that's your problem. If you owe the bank $100 million dollars, that's the bank's problem."

So, the burden ultimately falls on the banks which need to make massive provisions. Since majority of the corporate loans are written off by state-run banks which control nearly 60 percent of the total assets of the banking system, the big pain will be felt by PSBs owned by the government.

The government controls 57-98 percent stake in PSBs and routinely infuses capital in these banks to support their falling capital ratios. We all know how the government generates money. Now, let’s go back to the question—who pays the price of massive loan write-offs? Answer is simple - it’s us, the taxpayers.

Banking Central is a weekly column that keeps a close watch and connects the dots about the sector's most important events for readers.Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.