The English word “paradise” comes from the old Iranian “pairidaeza”, which originally meant a walled garden. The Persians were known as the great gardeners of antiquity; Greek historian Xenophon, for example, writes of Cyrus the Younger declaring to an impressed Lysander that he had planned the gardens of Sardis himself. Whenever he was not campaigning, the Persian king went on, he gardened before dinner.

Since then, many have cast about for their own versions of paradise. Those less privileged may wonder why Pico Iyer, who currently divides his time between peaceful Nara in Japan and a Benedictine hermitage in California, would venture forth to do the same.

He seems, however, to have always been smitten by wanderlust. The subtitles of his non-fiction over the years are proof enough of this. There are reports from the not-so-far East, travels to some lonely places of the world, and accounts of jet lag, shopping malls, and the search for home.

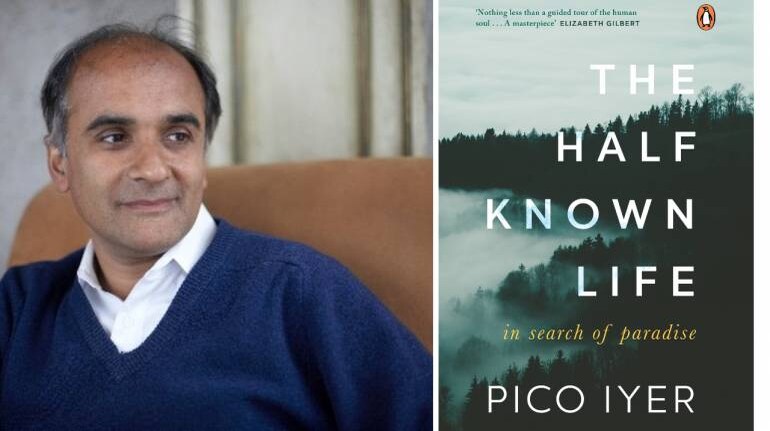

Iyer continues these odysseys in his new work, The Half-known Life: In Search of Paradise. This is a series of closely-linked essays, parts of which have appeared in unmodified form elsewhere. The common theme is to discover whether an earthly paradise can be found in a world of unceasing conflict, and whether the search for it might not aggravate differences.

It starts with Iran, appropriately enough, where competing visions crisscross “with furious intensity”. Iyer visits Ferdowsi’s tomb in Tus, as well as other landmarks such as Shiraz, birthplace of Hafez, and Qom, often referred to as the spiritual centre of the country.

He senses “passionate displays of religious surrender from those who wished to have no part of religious rule”, creating “a treasure house of riddles”. As his articulate tour guide informs him, those who come here thinking Iran is an enigma leave with an even richer sense of being puzzled.

Iyer’s earnestness cuts both ways. There is a willingness to learn and contemplate, but there is also a hushed tone that leads to descriptions such as those of Iran’s “lacquered beauty and the iron presence” which “constantly shimmered a little out of reach”.

In other places, one sees the same curiosity shot through with hands-off reflection. He visits North Korea, the so-called people’s paradise on earth, because “I refused to believe that humanity could ever be entirely suppressed; at some point, surely, it has to peek out from behind the gates of ideology”. In Jerusalem, where conflict is “not just between traditions, but within them”, he finds that he is “catching passion like a fever”.

Elsewhere, he gushes over the “dusty alleyways of Old Srinagar, [where] white-bearded elders were hobbling along on canes towards the house of prayer, while fair-skinned girls with the green eyes of Afghanistan smiled and sparkled under shawls of orange and yellow and blue”. That sounds like a depiction from a Merchant-Ivory production.

He is astute enough not to over-romanticise. A potted history of the state’s troubled past is followed by the observation that “the jostle and exoticism of an ancient place” is surrounded by the checkpoints, barbed wire, and armed patrols of “a never-ending modern conflict”.

Yet, a dated quaintness persists. At one point, he muses: “Even now, much of India has this feeling of a fictional, dressed-up England created by displaced Brits glad to be far from the land they knew.” Really, now.

Of Varanasi, he writes that the city has always been described in mystical terms. It turns out that he can fall prey to this, too. Figures in blankets appear through the mist, and cows, pariah dogs, and red-bottomed monkeys trot in and out of temples. Here, paradise has to be found “not just in the middle of life, but in the midst of death”. This “city of burning bodies” was “like the skull on a monastic’s desk, reminding us that time is never so limitless as we think”.

The book does contain moments of moving rumination. In Sri Lanka, he is rattled and unsettled; to him, the idea of paradise on this island seems to corrupt moments of beauty, making people not kinder but more reckless. In Jerusalem, the interiors of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre provide a meditative haven, and elsewhere, he comes across a sign that reads: “Please: No Explanations Inside the Church”.

Iyer does not write a great deal about the people he encounters on his travels, apart from noting the informed and sometimes shop-worn observations of tour guides and taxi drivers. The intent is to match journeys within with those without, and the account is leavened with trips into his past.

Thus, we read of his mother’s recollections of visits to Kashmir; his student years in England where he succumbs to almost Edwardian games of tennis in the golden light of summer evenings; conversations with the Dalai Lama; and touring Belfast with his wife where he surprises her with his knowledge of Van Morrison’s output.

Towards the end of the book, Iyer describes another sojourn, this time to the temple settlement of Mount Koya in Japan. When free from demanding monastic rituals, he finds solace in Emily Dickinson who wisely, if enigmatically, informs him: “Wonder is not precisely knowing and not precisely knowing not.”

Many places have been termed Edenic, but as he notes during his Iranian sojourn: “Find a heaven within, Rumi had written…and you enter a garden in which one leaf is worth more than all of Paradise.” Given the state of the world, Voltaire would have agreed. As he once proclaimed: “Wherever my travels may lead, paradise is where I am.”

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.