She is a fine writer. She is very conscious of the tempo of the book, and this is never at the cost of depth. Striking this balance is important especially because people’s attention spans have shrunk. She is skilled in the art of turning conversations into extremely readable books.

For Talking Films, I discussed with her my experiences as a screenplay and dialogue writer and gave my perspective on how characters are developed.

For Talking Songs, I spoke not only about songs that I have written but also about the rich and long tradition of using songs in Ramlila, Parsi theatre and other narrative forms before the emergence of Indian cinema.

With Talking Life, our intention was to highlight the unusual people I met along my journey, from childhood to this age, by recalling the incidents that I experienced or witnessed. People tend to forget what happened several decades ago but thankfully I have a good memory. This is not an I-me-myself kind of book. That would have been boring for myself, and for readers.

Our aim here is to give people slices from my life that feature interesting and strange individuals. It is a dialogue rather than a biography.

Talking Life: Javed Akhtar in Conversation with Nasreen Munni Kabir (2023, Westland Books)In Talking Life, you mention how communism was an important force in the intellectual and literary worlds of your parents Jan Nisar Akhtar and Safia Akhtar…

Talking Life: Javed Akhtar in Conversation with Nasreen Munni Kabir (2023, Westland Books)In Talking Life, you mention how communism was an important force in the intellectual and literary worlds of your parents Jan Nisar Akhtar and Safia Akhtar…Half of my family was made up of hardcore communists; the other half were hardcore Congressmen. Humko dono ki training milti thhi (We got trained in both). During my childhood in Lucknow, I would see the national flag being hoisted on the 15th of August (Independence Day) and unfurled on the 26th of January (Republic Day). After the ceremony, it was folded respectfully and kept on the highest shelf of a cupboard. One afternoon, when everyone else was asleep, I quietly dragged a stool and stood on my little toes to touch the flag. I must have been six or seven years old at that time. I was filled with awe. The curiosity and the desire to touch it came from the atmosphere that I grew up in. The national anthem and flag were given great respect.

This story co-exists with another one. When I was four or five years old, one of my school teachers asked us to draw a flag. I ended up drawing a red one because of the Communist influence in my family. It seems a bit funny now but I was so innocent that I used to think of Stalin as my grandfather then. That must have happened because we had a huge portrait of him in our house. I was convinced that Ghalib was my uncle because someone told me so. When I realised that my beliefs were not true, I was deeply disappointed and disillusioned.

In this book, you also refer to a biography of Prophet Muhammad that was written for children. When your grandfather gave it to you, it 'opened a whole new universe…of great mystery and adventure'. Have you considered writing books for children?This is a great question! Well, to be honest, I don’t think I have the innocence that is required to write for children. I do have a child in me but he is a very naughty and precocious child. He is like Dennis the Menace. My ex-wife, Honey Irani, is the one who is really good at writing stories for children. Two of her books came out recently. One is called Shakya’s Little Secret (2022), and the other is called Akira, Shakya, and the Grouchy Owl (2022). She is just brilliant. They were released just a couple of months ago. She has done a superb job. I am not sure if I can.

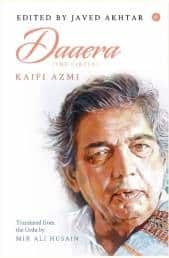

'Daaera: The Circle' (2022), Kaifi Azmi's poems translated by Mir Ali Hussain, edited by Javed Akhtar

'Daaera: The Circle' (2022), Kaifi Azmi's poems translated by Mir Ali Hussain, edited by Javed AkhtarMy wife Shabana Azmi, who is Kaifi sahab’s daughter, came up with the idea. She said, “I will select 25 poems written by your father, and you select 25 poems written by my father. Let us get these translated into English.” Thanks to Westland Books, we were able to release a box set of two books — Daaera: The Circle and Dhanak: The Rainbow. Mir Ali Husain has translated Kaifi sahab’s poems, and Sumantra Ghosal has translated my father Jan Nisar Akhtar’s poems that were selected by Shabana. Along with the English translations, the readers can also read the original nazms in the Nastaliq as well as Devanagari scripts. Shabana and I enjoyed selecting the poems, writing the prefaces, and editing the translations.

What are your thoughts on the role of translation in promoting Urdu literature today?Translation is important for promoting not only Urdu literature but literature in most languages. Many of us in India are able to read Russian, French, Czech and Italian literature only because of translations into English. Victor Hugo, Anton Chekhov, Franz Kafka, Alberto Moravia, Maxim Gorky, and Honoré de Balzac are the writers that immediately come to mind. Without English translations, so many of us would not have read Bengali classics by Rabindranath Tagore and Sarat Chandra Chatterjee. What a frightening idea!

We would have been ignorant and impoverished without the great skill and hard work of translators. Surely, some fragrance of the original is lost in translation but let us focus on what is preserved. In my opinion, prose seems a lot more open to translation than poetry because the latter is filled with metaphors that cannot be unlocked with just a dictionary.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.