Graphic designer Stephen Doyle’s new show features sculpture crafted from books, with paper patterns arising from their pages. A Mumbai bakery regularly advertises “book lover cakes” in the shape of printed volumes. And if you search for #bookstagram on your favourite image sharing app, you’ll come across over 60 million posts.

Those are just three examples of what literary scholar Jessica Pressman calls “bookishness”. In her new book with the same title, she defines it as an omnipresent 21st century phenomenon of “creative acts that engage the physicality of the book within a digital culture”.

She provides several other examples. Mobile phone and e-book covers crafted to look like old books; decorative pillows with images of books; earrings and necklaces resembling miniature classics; and, memorably, Jane Austen-inspired leggings with sentences from her novels printed across them. “It is now commonplace,” she writes, “to find the presence of the book where it is not actually physically present”.

Pressman feels that this love for the book as symbol and artefact, spanning art, cyberspace, and kitsch, emerged during the 1990s as a response to anxieties because of the digital age. As Leah Price, who’s written about the ways that books were used in Victorian England, states, “Every generation rewrites the book’s epitaph; all that changes is the whodunit.”

Bookishness also influences the online world itself. Apple’s iBooks app was initially designed to look like a wooden bookshelf with covers facing outwards. There’s also the page-flip effect in many reading apps, which mimics a page being turned manually. As Baudrillard said decades ago, the simulacra supplants the real.

One way to look at this is in terms of what cultural theorist Raymond Williams identified as “the residual”. This is a practice or product that belongs to the past but is still active in the present cultural process. Such a residual can also be seen in music, with vinyl records remaining a touchstone for many.

For literary culture at a time of change, bookishness is a way of maintaining a commitment to traditional codes. Pressman’s ambit throughout is Eurocentric, which can be a pity; contextual references to earlier shifts in China and Mesopotamia, for example, could have been useful.

It’s not just about being more familiar with the look and feel of a printed book. As Pressman points out, bookishness can promote desirable traits because of a physical nearness to books, and not from the reading of them. Class and consumerism play a role in “constructing and projecting identity through the possession and presentation of books”.

Volumes bought in bulk to fill bookshelves and bookish backgrounds on Zoom are two examples. The tendency is most visible on online image platforms, with titles tastefully arranged on indoor and outdoor surfaces next to cups of coffee, preferably black, and spectacles, preferably stylish.

Performative aspects aside, bookishness also manifests itself as a counter to the ceaseless onrush of the digital world. Here, books – and bookshops -represent a safe and comforting harbour.

Pressman’s reading of experimental novels such as Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves and Steven Hall’s The Raw Shark Texts show how they use the sheer physicality of text as a defence against a digital onslaught. Other works such as Jennifer Egan’s The Keep and Jonathan Safran Foer’s Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close also demonstrate a vision of traditional books as modes of protection.

This year itself, there was also Hugo Hamilton’s The Pages. Ingeniously, the narrator of this novel is another novel, Joseph Roth’s Rebellion. This functions as a survivor and bulwark against disarray: “I have accumulated the inner lives of my readers. Their thoughts have been added in layers underneath the text, turning me into a living thing, with human faculties. I have the ability to remember. I can tell when history is in danger of repeating itself.”

Other pronouncements on the virtues of slowing down and immersing oneself in a physical book may well come from a position of privilege. Early in the 20th century, Edith Wharton captured something of this sensibility when she wrote: “The true felicity of a lover of books is the luxurious turning of page by page, the surrender, not meanly abject, but deliberate and cautious, with your wits about you, as you deliver yourself into the keeping of the book. This I call reading.”

Now, such cherished associations are being challenged, creating understandable discomfort. There are new types of literature (in which one can include video games and fan fiction) and new ways of reading (hyperlinked and networked sites). These may threaten older assumptions, but they don’t mean the end of literary sensibilities.

None of this is to say that the physical book is on the verge of going extinct. Far from it: surveys in the US even say that sales are increasing year on year. It’s simply that, as Simone Murray has asserted, books “are created, edited, marketed, publicized, retailed, profiled, evaluated, and discussed within a thoroughly digital web of stakeholders”. In the words of N. Katherine Hayles, “digitality has become the textual condition of twenty-first century literature”.

Bookishness, then, serves as a signifier of such changes, and a record of loss and remembrance. Understanding how our relationship with words has changed, and recognising bookishness as a way of navigating this shift, is what Pressman’s clear-sighted study brings to light.

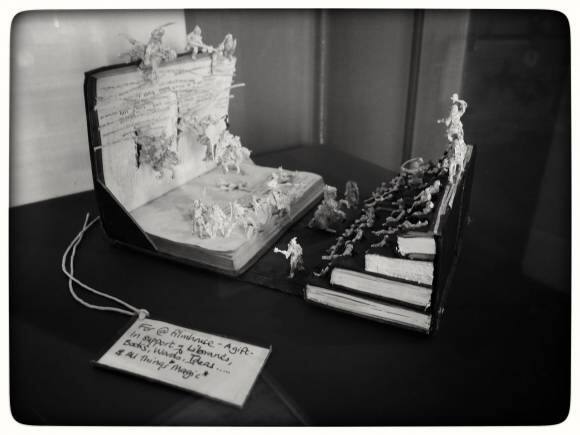

Representational image: a book sculpture carved out of copies of 'Filmhouse'. (Image: marsupium photography via Wikimedia Commons 2.0)

Representational image: a book sculpture carved out of copies of 'Filmhouse'. (Image: marsupium photography via Wikimedia Commons 2.0) Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.