Despite the advances in meteorological sciences and investment in India’s Meteorological Department, accuracy in the prediction of the Indian monsoon continues to be challenging. Last month, the early arrival of the monsoon in Kerala was in the national headlines, and it was thought that India would be inundated with early and even excessive rains. But after 29 May 2025, the monsoon has almost stalled, and there is a possibility that south-western regions, mostly growing pulses and oilseeds, may not receive bountiful rains in the next two weeks. As of 13 June, rainfall in Kerala is deficient by 47 percent, and even Konkan and Goa are lower by 26 percent. The entire North East is lower by 36 percent.

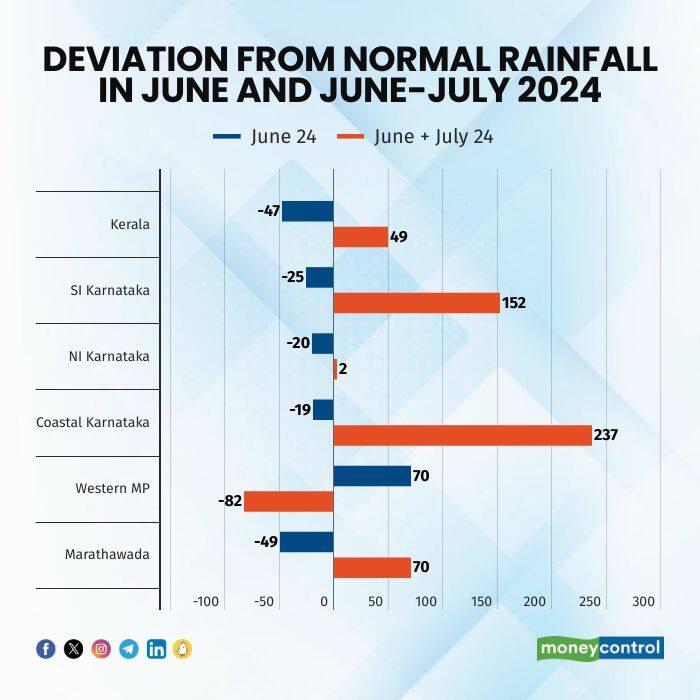

If we consider last year’s monsoon, it is found that there was highly deficient rainfall in July 2024 in western Kerala, coastal Karnataka, and Marathwada, but by the end of July, the deficit was wiped out, and these regions were in the positive. Western Madhya Pradesh had 70 percent excess rainfall in June, but by the end of July, it was deficient by 82 percent. The following chart depicts the deviation from normal rainfall in June and June–July of last year.

Government Invests in Upgradation of IMD

To improve the functioning of the IMD, the Government launched the National Monsoon Mission (NMM) in 2012 with the objective of establishing a dynamical prediction system for seasonal forecasts and improving monsoon forecasting skills in the country. An amount of ₹400 crores was allocated in 2012–2017 and ₹151 crores in 2017–18. In 2021, the IMD implemented a Multi-Model Ensemble Approach to further enhance its forecasting accuracy.

In September 2024, the Government approved Mission Mausam with a budget outlay of ₹2,000 crores over two years. The objective is to substantially enhance the capability of the IMD for modelling and forecasting.

An evaluation by NCAER found that the total annual economic benefits (from these efforts to modernise IMD) to agricultural households were ₹13,331 crores, and the incremental benefit over the next five years is estimated to be about ₹48,056 crores for the farming community.

IMD’s April forecasts have also become more precise, with deviations of only 2.27 percent in actual rainfall from 2021–2024, well within the forecast range of 4 percent.

High Agricultural Growth But Concerns Persist

Due to good rains in subsequent months, agricultural output reached record levels in 2024–25, and the Gross Value Added (GVA) in agriculture and allied activities reached a high of 4.6 percent, up from 2.7 percent in 2023–2024.

This year also, the IMD forecast seasonal rainfall at 105 percent of the Long Period Average (LPA), with a model error of ±5%. The LPA of monsoon season rainfall for 1971–2020 is 87 cm. In its updated forecast of 31 May, IMD has projected that there is likely to be normal or above-normal rainfall over most parts of India. But in the Northwest, East and Northeast India, there is a possibility of normal to below-normal rainfall. This means that rainfall in early Green Revolution areas of Punjab, Haryana and western Uttar Pradesh may be normal or even deficient.

IMD will issue monthly rainfall forecasts around the end of June, July and August respectively for the subsequent one month. While one hopes that the stalled monsoon will revive, IMD’s forecast for July, a critical month for Kharif sowing, will be available only towards the end of June 2025.

It seems that the Government has considered the possibility of lower rainfall in the north-western region and, therefore, imposed a stock limit on wheat on 27 May 2025. It will remain effective until the status of the new crop of wheat is known, 31 March 2026. It is possible that the Government is still concerned about the inflationary pressure on food due to erratic monsoon rainfall in the most productive regions of the Northwest and East. This is despite a record-high wheat production of 117.5 million tonnes and procurement of 29.92 million tonnes -- the highest since 2021–22.

Similarly, the Government on 31 May 2025 notified duty-free import of yellow peas until 31 March 2026. There is no minimum import price or port restriction. The basic customs duty on crude palm oil, crude soybean oil and crude sunflower oil was also reduced on 30 May 2025 from 20 percent to 10 percent. It must be noted that duty on these crude oils was increased from zero to 20 percent on 14 September 2024. This was done to help the farmers of oilseed crops realise the MSP, especially for soybean and mustard. It is a different matter that the effort did not bear fruit due to a crash in the prices of soymeal, which was due to the availability of much cheaper meal from maize, a by-product of ethanol manufacturing.

Summing Up

The agricultural scene is still quite dependent on the monsoon, especially in rain-fed areas where oilseeds and pulses are grown. There is a need to ensure that the landed cost of imported pulses and edible oils remains above the MSP so that farmers do not lose the incentive to grow the same. This year, it is quite possible that the area under soybean may be lower, and the farmers may prefer to grow maize. The Government took a good decision to waive the ceiling of 25 percent procurement of pulses produced in a state. If farmers receive a good price—at least the MSP for pulses and oilseeds—they will continue to grow them.

And it may be prudent to impose at least a 5 percent duty on all future agri-imports.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.