You can take a horse to water, but cannot make it drink, goes the hoary chestnut. The Reserve Bank of India can flood the banking system with liquidity but it cannot make banks on-lend these funds. After the last set of measures announced on March 27, banks have taken to parking as much as Rs 6.9 lakh crore at the central bank’s overnight borrowing window (through an operation known as reverse repo). Other measures such as lending funds to banks for the specified purpose for buying corporate bonds has worked, but only the big boys are beneficiaries. Non-banking financial companies, which extend credit in places where commercial banks can’t go or do not want to go, were mostly left out in the previous set of announcements.

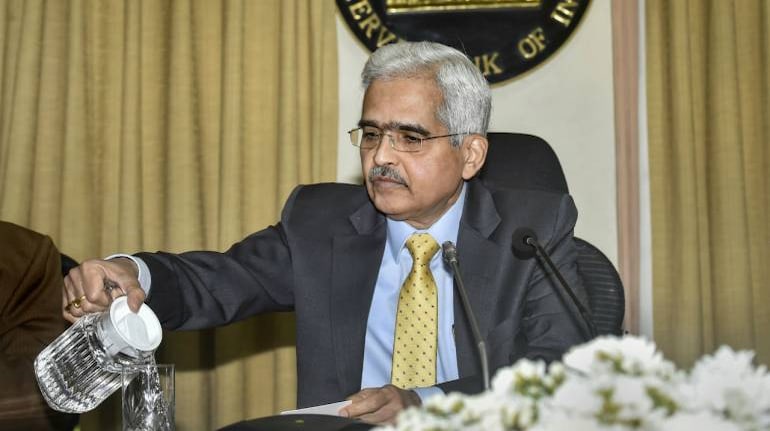

So, the central bank announced another set of measures where it plans to inject more liquidity into the banking system, get banks to lend to the entities – typically small and midsize firms which need it the most---and also offer banks some relief in terms of classifying loans as non-performing. It is a step in the right direction, but given the disruption that COVID-19 is causing, does it go far enough?

What has RBI done?

It has said that banks will be able to borrow Rs 50,000 crore (to start with) from the central bank for the express purpose of onlending it to small and mid-sized NBFCs and microfinance companies. It has given another Rs 50,000 crore to the likes of NABARD (National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development), NHB (National Housing Bank) and SIDBI (Small Industries Development Bank of India) which again provide funding to companies that provide small business finance, housing finance and so on. Thus, RBI has tried to address the issue being faced by NBFCs and HFCs which faced difficulties in accessing funds.

Second, it has cut the reverse repo rate – the interest banks get when they park funds with the central bank in its overnight borrowing window – by 25 basis points. It also cut the LCR (liquidity coverage ratio) which, shorn of the jargon, means that banks have more money to lend. Besides, it has told banks not to distribute dividends to bolster their capital position.

Third, it has told banks that they can exclude the 90-day period from 1 March to 31 May in calculating the days past due for loans and classifying bad loans. In other words, loans which were standard as on 1 March 2020 and which have been offered a moratorium shall not count as NPAs. RBI has also told banks to make a 10 percent additional provision on loans where a moratorium has been offered, spread over the March and June quarters, which can be adjusted against actual slippage.

These are good measures, but don’t go far enough. Look at the markets. The 10-year bond yield fell a mere 8 bps to 6.362 percent from the previous close 6.44 percent. The broader market and financial sector stocks have given up some of their gains.

The key problem here is not of liquidity but risk aversion. Cutting the reverse repo or the LCR won’t be enough to make banks lend to risk to smaller firms which are the most vulnerable. Of course, one can’t blame banks for being risk averse or prudent. But what it means is that the RBI has to convey to them it has their back. It has to assure banks that they won’t have to carry a pile of NPAs once the crisis ends and give them the confidence to lend.

Moreover, the central bank should actually consider buying corporate bonds itself or getting the government to do so for direct support to corporate credit like the US Federal Reserve has done. That will be one way to ensure that credit flows smoothly to those who need it the most.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.