Economic reappraisals and disappointments seem to overpower the hallmark festivity this October. While consumer spending may soon burst forth, the dismal external outlook with a recession looming on the horizon, high inflation and copious uncertainties, does raise questions about its longevity. The sense of a relapse instead of recovery gaining ground with progressive strength has begun nagging. Consider some key developments and data signals.

At their annual meetings, the World Bank and the IMF scaled down India’s growth projection for FY23 to 6.5 percent and 6.8 percent respectively, from 7.5 percent and 7.4 percent before. The shock prone world economy is seen slowing to 2.7 percent next year, its weakest pace of growth since 2001 except the global financial crisis, and the critical pandemic year. A more abrupt braking is foreseen in world trade, an outstanding constituent of output; goods’ trade volumes are visualised rising just 1 percent by the WTO after growing 3.5 percent this year. Inflation, tightening financial settings, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the pandemic’s enduring effects are all contributors.

No matter the bravado that India can dodge this better than most because of its larger domestic demand base, we must recognise that exports added the most, 5.7 percentage points (not counting imports), to the 8.7 percent GDP growth last year, enabling the strong pull-up from a -6.6 percent contraction of the pandemic. A 33 percent growth in non-oil exports, after negative growth for two years (cumulative -6.3 percent), was a hefty 30 percent rise over pre-pandemic levels (FY20). It’s as important to note the strong attachment this has with fixed assets’ creation, which contributed 5.1 ppts. So, the pinch from export-related losses to output and incomes is not inconsiderable. The slide is already visible in monthly data. The future uncertainty of external demand could take away more from the growth equation than currently anticipated.

We need to look more closely at domestic demand, mainly the consumer side, as the dismal environment blacks out investment with descendant fierceness. Private consumer expenditure, which added 4.5ppt to output growth last year, is the principal component. This isn’t assured at this point — subdued sales and cautious commentary of consumer goods’ firms contrasts with robust indirect tax collections, vehicle sales, among other data.

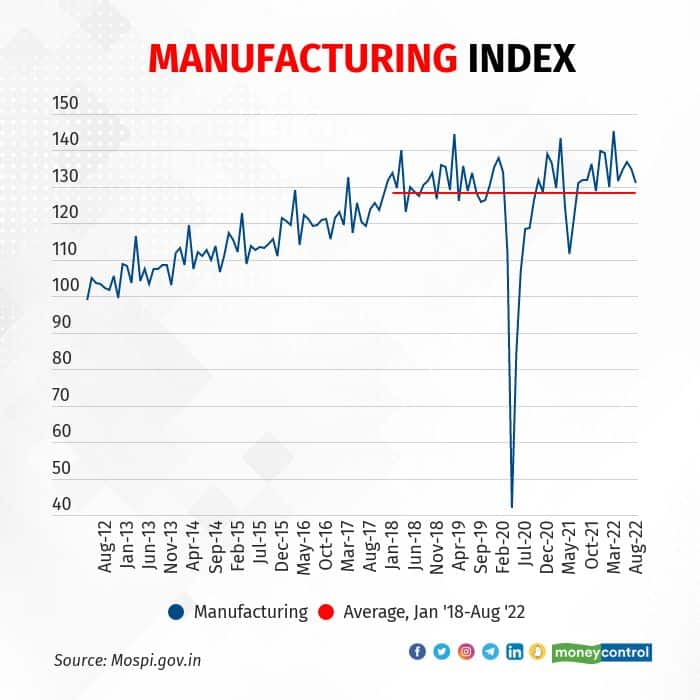

Industrial output data on October 12 offers a supply side preview. Overall industry grew -0.8 percent in August upon a strong base. A sense can only be had therefore in relation to pre-pandemic levels; a longer trend allows better grasp of production strength. Take a look at the manufacturing index – this is essentially flat, at least from 2018 or four and half years.

This year, industry growth averaged 3.2 percent in April-June over comparable 2019 base; in this quarter, the two-month average rise is 1.5 percent. That doesn’t look like demand is firing up. From a longer perspective, the trend flatness is disturbing.

The picture from consumer goods, durable and non-durables, is more disheartening. Durable goods’ output is inclining down even before 2018, a trend growth of -2.2 percent; the index hasn’t restored to period average level so far this year. Non-durable goods’ output fares slightly better but a 1.1 percent trend growth indicates consumption has been subdued for quite some time. The overall revelation is of weak demand as non-durables include quotidian consumer items such as food, spices, beverages, fuel, cosmetics, cleaning products, textiles, clothing, footwear, personal and numerous other products.

The third chart shows the depth of severity relative to level three years ago, i.e., comparable periods in 2019. Consumer goods’ production is considerably below in each quarter this year. In the last two months, the shrinkage in non-durable goods’ output deepened, while durable goods continue in accordance with its trend decline.

There appears little retrieval as seen from industrial output growth. Are we staring at a relapse, given inflation’s impact upon consumers’ real purchasing capacity? Some indication of this might be the recent announcement of price reductions by some big consumer goods’ firms, who now seem to be chasing demand after a year of preserving margins by passing on their increased costs to final consumer prices.

The October 12 data also showed a food price-led rise in September’s retail inflation to 7.4 percent. Prognosis of a satisfactory decline in price growth is unfavourable. International oil prices have climbed. Food price pressures are expected remaining firm and/or hardening from multiple factors, viz., lower rice acreage sowed, heavy unseasonal rains, inadequate wheat stocks preventing market-stabilisation sales, seasonal demand, etc. Inflation expectations and wages could respond unfavourably, force tighter monetary policy, and further cut in consumer expenditures.

The confluence does not favour consumption upon which growth is majorly dependent. Will we see more downgrades ahead? On September 30, the RBI also lowered its growth projection to 7 percent, 80-bps down from the initial February forecast (7.8 percent). The IMF, which forecast 9 percent GDP growth in January, totals 160-bps reduction to October. Let us wish no more cropping ahead.

Renu Kohli is a New Delhi-based macroeconomist. Views are personal, and do not represent the stand of this publication.Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.