Faced with a severe Balance of Payment crisis in 1991, the Indian government embarked on an economic reform programme favouring decentralisation, de-bureaucratisation and globalisation. What began as a response to an economic crisis has led to an unprecedented environmental crisis that is set to reverse the little gains made in the last three decades.

The prime objectives of the new industrial policy were to introduce liberalisation measures to integrate the Indian economy with the world economy, abolish restrictions on direct foreign investment, liberate indigenous enterprise and achieve international competitiveness.

The past 30 years can be largely summed up as a story of spectacular economic performance and rapid environmental degradation. While India may have moved from a low-income country to a middle-income one, its growth has not been ‘inclusive’. A large number of poor, marginalised and vulnerable sections of the society have been left out of the growth process.

While India may well be on the path to eradicating extreme poverty, it still lags behind in other important development indicators, especially regarding health and education. The reforms were largely in the formal sector of the economy, the agriculture and forest dependent communities did not see any reforms leading to uneven growth and unequal distribution.

In his 1991 budget speech, Finance Minister Manmohan Singh made an emphatic declaration: "We cannot deforest our way to prosperity, and we cannot pollute our way to prosperity." These were prophetic words.

Three decades later, forests nearly two-thirds the size of Haryana have been lost to encroachments (15,000 sq km) and 23,716 industrial projects (14,000 sq km), according to government data. Artificial forests cannot compensate the loss of biodiversity, as the government recently acknowledged. The increase in air and water pollution is mainly from iron, steel, cement, coal, petroleum, fertilisers, synthetic resins, plastic, artificial fibres and chemical industries — all which benefitted from the reforms.

Trade liberalisation in India systematically removed trade barriers and restrictions on foreign direct investments (FDI). As developed countries started cleaning up their environmental Act, not surprisingly most of the post-1991 FDI investments to India were higher in dirty technologies and polluting industries.

According to State of Environment Report, 2021, by the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), of 88 major industrial clusters in India, 35 showed overall environmental degradation, 33 pointed to worsening air quality, 45 had more polluted water, and in 17 land pollution became worse.

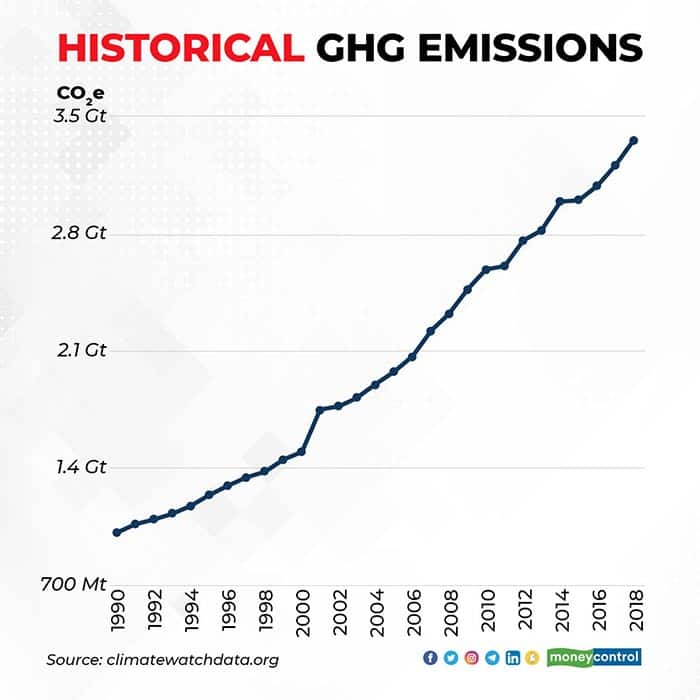

The major greenhouse gases (GHG) added to the environment as a result of increased industrial activities include carbon monoxide (CO), carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrogen oxide (NOx), nitrous monoxide (N2O) and sulphur dioxide (SO2). In a report published by Climate Watch (2018), India ranked among the world's top-five contributors to GHG.

India’s automobile industry boomed after economic liberalisation, with a host of collaborations between Indian companies and leading car manufacturers worldwide. Along with this boom there has been an increase in the levels of air pollution. Twenty-one of the world’s 30 cities with the worst air pollution are in India. Air pollution in India has caused losses of up to Rs 7 lakh-crore ($95 billion) annually, according to Confederation of Indian Industry (CII).

In India, environmental statutes, though impressive in range and coverage, are more often observed in breach than practice. Corruption, jurisdictional conflicts and lack of co-ordination among different agencies has resulted in poor enforcement. India was ranked 168th out of 180 countries in the 2020 Environmental Performance Index (EPI), according to researchers at Yale and Columbia universities.

Interestingly, it is the courts, especially the Supreme Court and the National Green Tribunal that played a pivotal role in addressing the environmental crisis unleashed by economic reforms. The orders and directions of the apex court cover a wide range of areas, whether it be air, water, solid waste or hazardous waste. But none of it is enough to address the greatest threat to India’s economy - climate change.

The World Economic Forum’s 2020 report on global risks indicates that biodiversity and climate-related risks are now widely acknowledged to be the risks with the highest likelihood and impact. India can no longer afford to have an isolated climate policy, or one that places business interests over environmental concerns — as the draft Environment Impact Assessment (EIA) Notification 2020 proposes.

Countries around the world are debating their versions of the green new deal. India must break from carbon-centric Keynesian economics and adapt to the 21st-century vision for carbon neutrality: Investments in its rural communities for forest restoration coupled with agroforestry, sustainable fisheries and horticulture, organic and low-carbon agriculture, green jobs through renewable energy, and energy-efficient green infrastructure.

It remains to be seen whether it is the government or the judiciary that acknowledge that in essence, ecology is economy. Apart from the business case, moving to an integrated ecology-economy approach is a matter of survival in an increasingly uncertain future.

Views are personal and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.