Dibakar Das Roy’s comedy Dilli Dark hit theatres last month. This is Samuel Abiola Robinson’s second Indian film after Zakariya Mohammed’s brilliant Malayalam sports drama Sudani from Nigeria (2019). In 2021, Tarun Jain’s short film Kaala, too, set in Delhi, showed a deep-rooted Indian racism. Jayan Cherian’s Rhythm of Dammam (2024) is the first ever full-length feature film on the Siddis (descendants of Bantu people of East Africa) of Karnataka’s Yellapur. This year, A Doll Made Up of Clay, a short film from the Satyajit Ray Film and Television Institute of India (SRFTI), about an African in Kolkata, was officially selected at the 78th Cannes Film Festival last month, among the 16 finalists from a global pool of 2,700, at La Cinef student-film competition.

These films humanise their African protagonist — what the Indian mainstream films and society are loath to do. If novelist-activist Arundhati Roy underlined in an interview how “Indian racism towards Black people is almost worse than white peoples’ racism”, Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s 2009 TEDGlobal talk spotlights the dangers of a “single story”, which “creates stereotypes” and “robs people of dignity. It makes our recognition of our equal humanity difficult. It emphasizes how we are different rather than how we are similar,” Adichie said, adding, “It is impossible to engage properly with a place or a person without engaging with all of the stories of that place and that person.”

In all of the aforementioned films, one stands out because it is an African’s story told by an African. The Yoruba-Bengali short film A Doll Made Up of Clay has been directed by Kokob Gebrehaweria Tesfay, an Ethiopian scholarship student of direction and screenplay writing at Kolkata’s SRFTI.

The 23-minute film tells the story of a Nigerian footballer Oluwaseyi (Ibrahim Ahmed), who came to Kolkata to play seven-a-side football after selling his father’s land, with the promise that he’d build him a villa. But, in India, disillusioned by a career-ending leg injury, he grows distant from his older and unmarried partner Geeta (Geeta Doshi) and seeks solace and identity by reconnecting with his ancestral roots, by making a clay doll with holy clay used for making Durga idols. He speaks into the ground, to his dead father/ancestor. He applies the holy clay on himself to heal physically and mentally. Oluwaseyi is a doll — a broken one — in the hands of fate. “Oluwaseyi is broken, physically and mentally, he can’t cure himself. That’s why he wants a spiritual rebirth and applies the clay. He becomes like a doll made up of clay,” says Tesfay, 28. Hence, the film’s title. As is Geeta, ostracised socially and unable to set herself free from her police-officer brother who’s dependent on her and dislikes the African man in her life. The siblings grew up on stories of Africa their sailor father told.

The Cannes selection was not only a “proud moment” but was a “good experience” for networking and connecting with people at Bharat Pavilion and “filmmakers from Singapore, Poland, etc., who were interested in making Indian content,” says Sahil Manoj Ingle, the film’s producer. Shot over four days, A Doll Made up of Clay is a collaborative effort. It has Indian producer, cast and crew, African director and actor, and a Bangladeshi editor (Mahmud Abu Naser). And, it is a “zero-budget project” of SRFTI’s Producing for Film and Television (PFT) department, meant “purely for academic purposes”. The team received resources and equipment from the institute but “no money to spend on the film, unlike the case with a diploma film,” adds Ingle.

Team 'A Doll Made Up of Clay', which screened at La Cinef competition at 78th Cannes Film Festival;(from left) executive producer Uma Kumari, producer Sahil Manoj Ingle, director Kokob Gebrehaweria Tesfay, DOP Vinod Kumar, and sound designer Soham Pal.

Team 'A Doll Made Up of Clay', which screened at La Cinef competition at 78th Cannes Film Festival;(from left) executive producer Uma Kumari, producer Sahil Manoj Ingle, director Kokob Gebrehaweria Tesfay, DOP Vinod Kumar, and sound designer Soham Pal.

When Ingle, a production student got the project, he went knocking on Tesfay’s door. Tesfay, who studied theatre arts and visual arts at Addis Ababa University, came to pursue filmmaking at SRFTI. The two put together a team with fellow SRFTIans — DOP Vinod Kumar, sound designer Soham Pal, music composer Himangshu Saikia, executive producer Uma Kumari, and outside actors: Geeta Doshi, a long-timer in SRFTI projects, and Ibrahim Ahmed, a Kolkata-based former footballer from Nigeria.

Ibrahim Ahmed in a still from the film.

Ibrahim Ahmed in a still from the film.

“The Boko Haram (jihadist militant insurgency) issue is a daily occurrence in Nigeria, in its northern side. They kidnap and kill people (foreigners and locals). They ask for ransom and release some. But, we believe, it’s all a game planned by the government,” says Ahmed, 20, who hails from the country’s southwest region. Tesfay left his home owing to a devastating civil war, Tigray War (2020-22), in north Ethiopia’s Tigray region. “My place, my home, is under another military country. If I want to go back now, I don’t have a home. That’s why I was questioning that in the film (through the Boko Haram reference). My family has already shifted to the capital Addis Ababa because they were not safe. The people are still struggling. Many of the young, including some of my friends, have died. The others become soldiers or have migrated to Europe or Saudi Arabia. They need freedom. They want to live. They want to secure their place. But they’re dying in my country,” he says.

Since he belongs to Africa, Tesfay’s projects are on African concepts. His “first project is also an African story in Kolkata. The second is also about racism. The third is a long-take Indo-African project.” The story of A Doll Made up of Clay, Tesfay says, is “based on Ibrahim’s life, about racism and his struggles. Ibrahim has been facing problems with renting accommodation, he’s faced racist slurs from people when travelling on a bus, playing football, etc., they call him Kaalu (Blackie).” Tesfay met Ahmed in between his film projects in Kolkata while he was searching for an African actor. “It is difficult to get African actors here. Even now, if I need an African mother or child, I can’t access them. I only have Ibrahim. So, I have to use him wisely,” says the young writer-director.

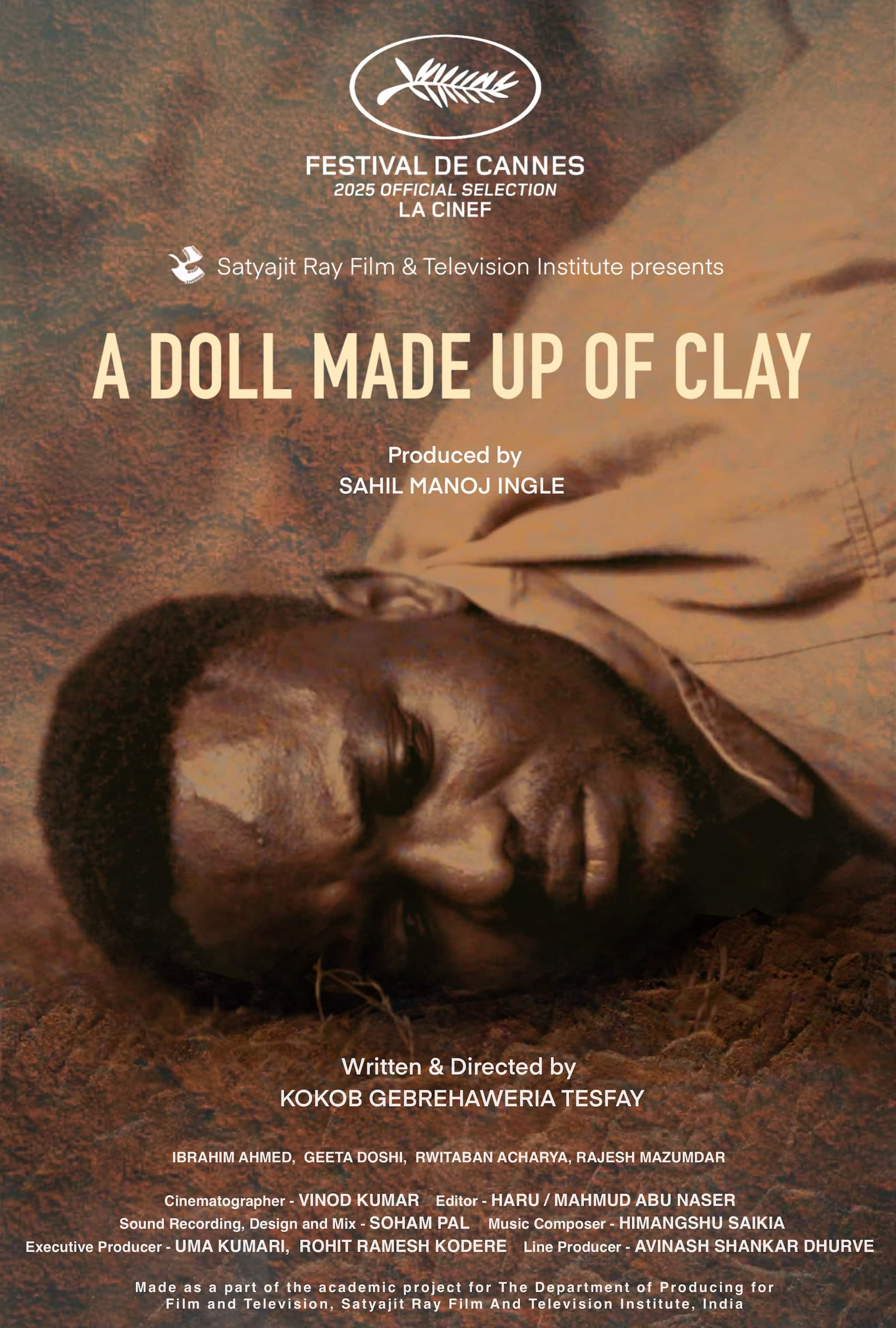

Poster of ' A Doll Made up of Clay'.

Poster of ' A Doll Made up of Clay'.

In the short film, Ahmed is remarkable and flawless. He exercises restraint and brings interiority to Oluwaseyi’s angst, dilemma, melancholy, grief, yearning for home/belonging. Ahmed took just 10 days to rehearse for the role. “Ibrahim is very expressive and his physique is very interesting,” concurs Tesfay, “From the long takes to the close-ups, he did very nicely as the main lead character. He has a scar on his hand and shoulder because of his football injury. This was the initial idea for my own short film, which I’m developing independently.” The first time they met, it was an emotional exchange. Ahmed narrated his story of struggle, and Tesfay recorded it on his mobile phone. The idea was to make a documentary, which he’s also developing. In that process, “I started knowing in detail about Ibrahim. How he came here, how he’s living and struggling, about the kind of racism he faces, his experience in Kolkata,” he says.

Football brought Ahmed to Kolkata. “I came here for a dream. My dream was to become a professional player,” he says, “I left my country with the hope that maybe I can make it out in India because I’ve heard about some African guys who made a lot of name in India as football players.” But when he arrived, things didn’t pan out the way he’d expected. “We are not professionals. We play seven-a-side and get paid for it. They call it ‘pay as you play’. If you play one game and you win, you can play another game, they give you money if you win. In a day, you can play three matches. But if you lose in the first game, you only get one game money and you are going back home. That’s how we survive. I got a leg injury and when we get injured, we don’t even have a proper doctor to treat us. We have to treat ourselves. Because of the injury, they don’t call us, and we can’t play. One of our guys, who was a football player, died in the last few months in Kolkata,” adds Ahmed, who has faced discrimination owing to his skin colour.

Ibrahim Ahmed, a Nigerian and former footballer living in Kolkata, in a film still.

Ibrahim Ahmed, a Nigerian and former footballer living in Kolkata, in a film still.

“In Kolkata, sometimes, people stare so much at you, it makes you feel uncomfortable. They call us Negro, Blackie… Not only me, I’m not the only one who has experienced all this. We feel it is because of the localised places we live in, full of uneducated people. I’ve been attacked by the locals in the Ruby area, including by my landlord, when I had come to India as a fresher. I was beaten with cricket bats and other tools and I got injured and had to go to the government hospital. Of course, we retaliated,” Ahmed adds, “We stay in such places because of lack of finances and purchasing power. We don’t like it at all, but now we are used to this racist name-calling because it mostly comes from the uneducated, not-so-good guys. There are also educated people in India who are good to us and engage in full conversations with us.”

In the film, the bit about healing an incurable illness with holy clay is an Ethiopian legend which Tesfay added to the script. “Ethiopia was not colonised (Africa’s oldest independent country), so we kept our tradition, customs, culture, food and costumes, it’s a bit different from the rest of Africa,” says Tesfay, “They have strong beliefs. The Ethiopian orthodox religion (Tewahedo Church) is one of the ancient (one of the oldest Christian denominations in the world), we follow both the Old Testament and New Testament. We have a lot of traditions. Mostly, we have holy water and holy clay, and there is this monastery in a forested mountain cave. It’s a bit scary. If somebody is possessed by spirits, they will be taken there, to apply the holy water or holy clay over the injury and the whole body, and leave him there for seven days, as they heal, they scream (a marker of being alive). That is the reason why I chose clay to cure the mental and physical illness of Oluwaseyi. I wanted his character to be courageous. The way he stands holding the clay doll is strong and graceful.”

Geeta Doshi and Ibrahim Ahmed in a still from 'A Doll Made Up of Clay'.

Geeta Doshi and Ibrahim Ahmed in a still from 'A Doll Made Up of Clay'.

Shot in 4:3 boxy aspect ratio, which evokes a sense of a character’s claustrophobia, being hemmed in by his situation, DOP Vinod Kumar’s cinematography is sharp, accentuating the dark, with minimal lighting. “The main idea was to create a dark mood, a mood of lifelessness, and to show the discrimination cycle,” says Tesfay about his abstract film.

For its minimalistic sound, Tesfay gave sound designer Soham Pal the brief to sonically replicate Oluwaseyi’s mindspace, “what’s going on in his mind”. Composer Himanshu Saikia’s music enhances the film, especially the ending. “Kokob and I sat with him on the music, and I mixed it,” says Pal, “We never visited Africa, so to create the soundscape in Oluwaseyi’s mind was a tough thing for us to do. But Kokob made me listen to a few African music to get an idea.” Soham and Himanshu “recreated the sound of two types of string instruments from my country: bagena and mashinko by using his (Himanshu’s) voice and a MIDI keyboard,” Tesfay adds.

A still from the short film, A Doll Made Up of Clay.

A still from the short film, A Doll Made Up of Clay.

Unlike Ahmed, Tesfay’s India experience has been happier. “I feel Kolkata for me is a kind of a home,” Tesfay says, “I often ask myself, what does home mean to me? Home is also the people. It’s been three years and five months that I didn’t go back home because a civil war was happening at my place. Even if I really want to go home, I can’t. My hometown Zalambessa, on the Ethiopian border [with Eritrea], is under another country’s military. I spoke to my mother, who’s living in my sister’s home in the capital [Addis Ababa] for more than three years but feels like she’s in a prison, away from her own home, friends, family and relatives.”

In the “artistic and progressive city” of Kolkata, he adds, “I have freedom. The people are good and innocent, especially those around me, who are very much into cinema. Yes, there are some moments when I feel I don’t belong to this place. At SRFTI itself, the aspirants are from all over India. They come from different cultures, languages, etc. I like India, India is an iconic country in the world, and is very famous for its history and films, particularly Bollywood. I grew up by watching the films of Shah Rukh Khan, Salman Khan, Aamir Khan and Akshay Kumar. I used to feel emotional. Cinema is the reason for me to come to India.” And, also, Satyajit Ray. “Everybody knows about him. I feel very privileged and lucky to sit in the institute named after the master and watch screenings of his films. I don’t know other Indian directors. I love his first film (Pather Panchali, 1955) in the Apu Trilogy,” adds Tesfay, whose inspirations closer home include African auteurs Haile Gerima (especially his film Teza, 2008), the late Ousmane Sembène and Abderrahmane Sissako.

A still from the SRFTI short film 'A Doll Made Up of Clay'.

A still from the SRFTI short film 'A Doll Made Up of Clay'.

Tesfay’s grand plan is to make a feature film in Ethiopia. “About the emigration of the young. It’s a political film about war. People are dying in the sea. If there is no peace, emigration will continue and people will die. My people are struggling to return to their homes. It’s very painful,” says the budding filmmaker who also plans on making a feature film in Kolkata. “I want to see India from the perspective of African filmmakers because they are my community. I want to make something based on the true incidents faced by the Africans in Kolkata. My next film is a documentary about asylum, about the struggles of this African community which came here for medical treatment and education. They want to go back but can’t because of the war,” he says, adding “I want to end the negative stereotyping of Africans in cinema” with his Indo-African projects.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.