Toni Morrison once said that she welcomed the label “black writer” because “I’m writing for black people”. Referring to James Baldwin mentioning “a little white man deep inside of all of us,” she continued, “the point is not having the white critic sit on your shoulder and approve it”.

Vintage, 304 pages, GBP 14.99.

Vintage, 304 pages, GBP 14.99.It was a mark of Morrison’s genius that she stunningly defied stereotypes.

The white critic on the shoulder, however, is what writers of colour still wrestle with. The West measures their work through lenses such as authenticity, representation and cultural credibility. One result, as Elaine Castillo writes, is that readers “end up going to writers of colour to learn the specific—and go to white writers to feel the universal.”

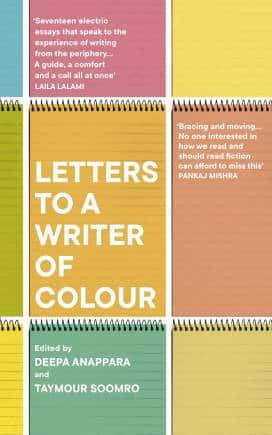

Work that doesn’t conform to these standards is often rejected as “badly written” or lacking in tension or conflict, as Deepa Anappara and Taymour Soomro put it in their introduction to Letters to a Writer of Colour. What’s missing is “the acknowledgment that these sensibilities had been shaped by, among other things, the white, mostly male aesthetic of the creative writing program itself”.

Anappara and Soomro’s jointly edited volume is an edifying series of essays by writers that pushes back against such unexamined and privileged assumptions. It is not merely a craft primer, though that would have been valuable enough on its own. What sets these essays apart is the way writers gracefully offer what they have learned as a hard-won product of their own personal circumstances.

There are lessons for readers, too. The anthology, as the editors point out, also offers “a new vocabulary to discuss fiction with others”.

Many essays explore questions of technique. On structure, Madeleine Thein emphasises that existing forms do not create the work: “they are measurements, rulers, and guideposts, like the lives lived before us”. On authenticity, Amitava Kumar feels that it can’t be “a single identity card or license that you carry in your wallet”. It takes varied forms, emerging from language and memory. On telling and showing, Jamil Jan Kochai explains how The Arabian Nights inspired his own work, with stories within stories acting as “confessions, jokes, historical accounts, gossip, digressions, tricks, seduction, and prophecies”.

Are writers of colour supposed to be funny? Only in specific ways, feels Tahmima Anam, based on her experiences with The Startup Wife. For a start, “you can make white people laugh, but you must make them sad while they are laughing”. And “if you are a POC man who wants to write darkly about a third-world politician, this is also okay…in that clever, arch, scathing way that will give you serious literary cred”.

Anam’s solution: write against expectations. “Every act of rebellion creates a little more space for people like us to write things that are not expected of people like us.”

As one such “POC man” who has written satirically about politicians, Mohammed Hanif narrates his own run-ins with his countrymen’s expectations of A Case of Exploding Mangoes. Many in Pakistan, he writes, “were not reading my novel as fiction but as an episode from our history”.

Also read: Does reading fiction make you a better person?

This perception was heightened when the novel was translated into Urdu. Though the translation made Hanif realise how much of it had been conceived in Urdu and Punjabi in his mind, it also led to defamation notices and confiscated copies.

Identities aren’t just about colour, of course. They intersect with gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity and more. Addressing this, Soomro writes of leading a double life in the past: “queer in London but not in Karachi, desi in Karachi but as English as possible in London.” He had to combat expectations of staying in the lane of “a good queer, a good immigrant” because “to resist simple narrow static definitions of who I am is to resist simple narrow definitions of what my fiction can be”.

Similarly, Zeyn Joukhadar says: “I wish I’d understood earlier that the queerness inherent to my life, my trans and Arab body, and my relationships—like the queerness in my English—is not a limitation but a strength.” His goal, and that of others, is a refusal to explain and instead “build an engine” to show the reader how it feels to be alive in a specific moment.

Beyond craft and interpretation, Deepa Anappara and Sharlene Teo grapple with issues of resilience. Anappara’s essay is a moving account of trying to find the ideal conditions to write while facing illness, bereavement, and dislocation, as well as overcoming a central dilemma: “To write like my peers in a Western classroom I have to erase myself, but if I erase myself I have no story.” Teo speaks of the burden of representation, and of training herself to stay attentive to how “the contours of my own identity and experience map into my imagination”.

Both storytellers and readers will find much to chew on in Letters to a Writer of Colour. The contributors also add reading suggestions for a further exploration of the issues raised. Fittingly, among the volumes that appear on more than one writer’s list is Matthew Salesses’s Craft in the Real World, in which he argues: “How we engage with craft expectations is what we can control as writers. The more we know about the context of those expectations, the more consciously we can engage with them.”

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.