It’s noon on a scorcher of a Sunday. The roads are near empty as most of Delhi takes the day off, barring exceptions such as hospitals, police, media, transport, etc., for whom all days are working days.

Not known to all, there is another department that works silently, behind the scenes, 24/7: the Met office.

This writer spent some time at the India Meteorological Department’s (IMD) National Weather Forecasting Centre’s control room at Lodhi Road to be part of the buzz at a time when the department is in the news because of the heatwave and cyclone Asani.

A few media personnel gather at the ground floor reception area of Mausam Bhawan, the IMD’s headquarters, waiting for senior Met officials to come down and provide updates.

Some of them are from Odisha, eager to get news about the cyclone, which is picking up pace over the Bay of Bengal. Others want to know about the heatwave that has shattered many a record.

After a while, the front office assistant asks us all to wait for a few minutes. The officials are busier than usual because of the developments surrounding the cyclone, he explains.

A few journalists are glued to three big screens that display real-time info on the weather. Others are looking at the giant photo frames of former IMD heads, adorning two walls of the lobby.

Senior Met official R.K. Jenamani comes down after some time carrying a bunch of papers, and readies to give news bytes and weather updates to the waiting reporters as they pan their cameras towards him.

Just before starting, he asks this writer to wait at the forecasting centre’s control room on the second floor.

Mausam Bhawan, DelhiThe control room, hub of the Met’s activities

Mausam Bhawan, DelhiThe control room, hub of the Met’s activitiesOn one side of the second floor is the National Met Communications Centre, which controls IMD’s dedicated communications network. On the right is the forecasting centre—the hub of all the IMD’s meteorological activities.

As one moves along the corridor towards the control room, one cannot but notice the different graphical presentations of IMD’s operations and history on the two walls.

At the end of the corridor is the control room, a big hall filled with giant screens and multiple workstations and desks with wide-screen computers displaying real-time information on the weather, along with graphics and satellite images — somewhat resembling a media newsroom; but minus the noise.

As it is a Sunday, only essential officials managing the most crucial desks are present—working almost silently, making calculations, jotting down notes and talking in almost hushed tones.

Some of them are huddled around a screen showing the progression of the cyclone, while one monitors the temperature map. Another official, a senior, moves from one desk to another, giving out instructions.

Senior scientist Jenamani, who heads the national forecasting centre, walks in a little while later. After taking some updates from his colleagues, he begins to explain how the whole system operates.

The control room has different desks monitoring the environment, cyclones and thunderstorms, temperature, rainfall, wind, fog, seismic activity, floods, etc., each managed by specialised units and personnel.

At the centre of the hall is a central terminal that keeps track of all activities.

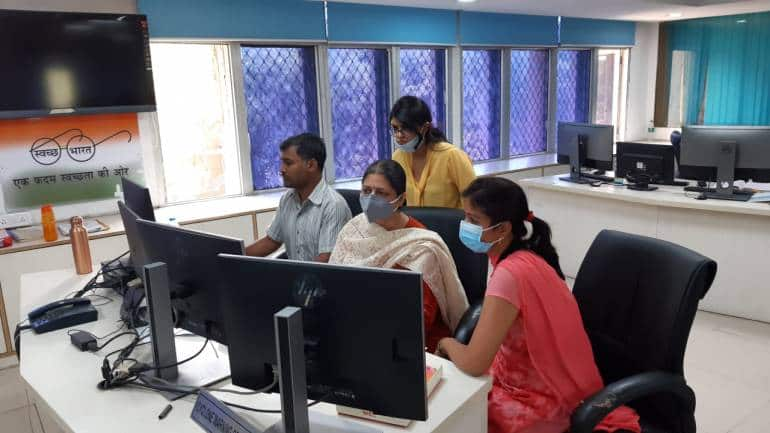

Officials monitoring Cyclone Asani.What IMD does

Officials monitoring Cyclone Asani.What IMD doesIMD’s operations can be broadly divided into two parts: public forecasting services and specialised sectoral offerings, Jenamani explains.

“The public services include general weather, cyclone and thunderstorm warnings, heat and cold waves, fog, snow, monsoon, pollution forecast, etc. It also includes the likely possible impact, risk factors, advisory, socio-economic fallout,” he says.

The sectoral services include specialised and customised forecasts for the aviation and marine sectors, oil exploration companies, conventional and non-conventional energy sector, agro-advisory, solar energy, national highways, railways, power distribution services and other sectors.

A complex network, always on its toesVisible to the public eye are the department’s weather bulletins and advisories on its website as well its social media channels and allied portals.

But what is hidden is the highly complicated, 24/7 back-end coordination among IMD’s multiple met and regional centres, weather stations and allied departments under the ministry of earth sciences, external agencies, state governments, as well as the processing and mining of loads of mindboggling data to provide accurate information to the public and parties concerned.

“All centres are working 24/7 to process information and provide accurate forecasts and advisories for the benefit of all,” he says.

During our conversation, a senior colleague comes and discusses some details about cyclone Asani. Jenamani quickly excuses himself and goes to the cyclone desk. A couple of calls are made to different centres and senior officials are updated about its progress.

Coming back to the discussion, the senior Met official tries to simplify the mega system that involves a complex network.

Say, for example, a cyclone is developing over the Bay of Bengal and is likely to directly affect two-three coastal states.

Information sent by the IMD’s local met stations and regional offices in these states is processed along with real-time satellite imagery and data by specialised teams sitting in multiple locations with the help of special software.

Periodical bulletins and advisories are then issued to the government agencies concerned and the media on the severity of the cyclone, its likely impact and even the socio-economic fallout.

Based on the bulletins, the local administration and disaster management authorities prepare back-up plans to deal with the situation and evacuate people, if needed, to minimise the loss of lives.

The National Met Communications Centre.Simple bulletins to risk-based forecast

The National Met Communications Centre.Simple bulletins to risk-based forecastThe department has come a long way from its beginnings in 1875, from issuing simple weather bulletins to becoming a sophisticated and highly advanced risk-based early warning system, Jenamani explains.

“Information is shared up to five days in advance so that the departments concerned can take precautions and preventive measures to minimise damage to human life and property,” he says.

The official explains how a rain forecast may be general for a state but the risk perception may differ from place to place. The impact of about 50 mm rain, for example, may be different on a sparsely-populated hinterland compared to a dense urban settlement in a city like Mumbai.

“So, when we issue a risk-based heavy rain forecast for, say, Mumbai, our data analysis will take into account the low-lying areas, traffic signals, drainage system, traffic volume, etc. All this info is sent by the municipality concerned.”

Rain forecast may be general for a state but the risk perception may differ from place to place. (Image: AP/ Rafiq Maqbool)Tracking the heat

Rain forecast may be general for a state but the risk perception may differ from place to place. (Image: AP/ Rafiq Maqbool)Tracking the heatWe move to the central desk, where the official shows a screen showing the heat map of India. As you scroll the cursor on a particular city, the map shows the live temperature of that place at that particular time. If you want to know the mercury of a specific neighbourhood, you zoom in further.

IMD has laid out well-defined standard operating procedures for all its weather forecasting and warning services and different operations.

For example, a heatwave is considered if the maximum temperature of a station reaches 40 degrees or more in the plains and 30 degrees or more in hilly regions, and stays that way for a specified number of days. The criterion will be, however, different for coastal and other regions.

Apart from the usual forecast, the IMD’s colour-coded (green, yellow, orange and red) heatwave and cold wave bulletins now include the possible impact on health and suggest dos and don’ts, the official explains.

Green is where no action is required, yellow implies we should remain updated, orange says be prepared and red alert means all hands on deck for action.

A severe heatwave swept through large swathes of India in April, the third hottest April in 122 years, the last being in 1901.

In parts of the north, northwest and central India, temperatures soared to 46 degrees Celsius. Though there was a slight respite after rains, temperatures are soaring again, prompting schools in Delhi-NCR to shift timings to early hours.

A severe heatwave swept through large swathes of India in April. (Image: AFP)Hi-tech exercise

A severe heatwave swept through large swathes of India in April. (Image: AFP)Hi-tech exerciseThe central terminal has access to all kinds of IMD-related information at the click of a mouse, be it rainfall or fog data of previous years or that of cyclones, storms or the environment.

Monitoring, tapping, processing, mining and real-time sharing of such data requires not only sharp minds but advanced and highly sophisticated technology that includes supercomputers, advanced Doppler radars, weather instruments, satellite systems, software, etc.

Our next stop is the Climate Info Processing System at the National Met Communications Centre, where the hard disks and processors are placed in floor-to-ceiling storage terminals in temperature-controlled rooms.

For numerical predictions and specialised forecasts, two super computers— Pratyush and Mihir—located at the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology – Pune and the National Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasting – Noida come in real handy, the official explains.

The Met department also has an exclusive communications network for uninterrupted and seamless coordination and dissemination of information.

Just as the central desk in Delhi functions 24/7, many other mini control rooms at the regional centres, allied departments and observatories work non-stop simultaneously for the unhindered flow of information to the public and IMD’s subscribers.

At about 10.30 am every day, a video meeting is held with state centres for updates and to arrive at a consensus on the weather forecast and other decisions.

“At least 10 officials are present in the main control room. We have people working in shifts 24/7, across centres. The entire team, including top officials, is present during big emergencies,” Jenamani says.

He says the IMD’s forecasting services are comparable with the US’s Global Forecast System and the UK’s Unified Model, and is fourth in the world in computing power.

The Met department has an exclusive communications network for uninterrupted, seamless coordination.Info on mobile apps

The Met department has an exclusive communications network for uninterrupted, seamless coordination.Info on mobile appsAt this point, another official points to the apps IMD has developed for the distribution of information.

IMD’s flagship Mausam app provides access to weather products available on mausam.imd.gov.in. Users can access weather forecasts, radar images and be warned of weather events.

Meghdoot Agro aggregates district and crop wise advisories issued by agro met field units with forecast and historic weather information for farmers. Damini monitors all lightning activity.

Weather info is also available on the Umang app, a single platform for pan-India e-Gov services.

So, what about the host of private players that also offer weather apps and forecast services? Jenamani says private participation is always welcome but they should fill in the gaps and not try to do what IMD is already doing.

“For example, there is a vast need to take information to rural areas and enhance agro-forecast services. This is where they can pitch in.”

IMD's reception lobby. Employees work in shifts, but during emergencies, it's all hands on deck.The last word

IMD's reception lobby. Employees work in shifts, but during emergencies, it's all hands on deck.The last wordHow does it feel to be working in an organisation where you deal with such sensitive information and have to be on your toes 24/7?

Jenamani says hailing from a vulnerable coastal village in Odisha that is highly prone to floods, cyclones and heat, he understands very well the importance of accurate weather forecasts.

“During my childhood, we lived in delicate mud houses. I have lived through the struggle for food grains, and seen how floods, drought and cyclones damaged our crops. I remember the flood of 1975, when we were evacuated after our house was submerged by flood waters,” he recalls.

When a person loves his profession and accepts that work is worship, he or she continues to work with the best possible effort, Jenamani says. “Also, as it concerns the safety and comforts of fellow human beings, it energises me and I live on that,” he says.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.