"Apni atmaa ke aaine ko pehchanne ki koshish karo/Try and identify the mirror to your soul,” Nitin Desai said during an online lecture in May 2020. In the lecture that posited art as that elusive mirror, Desai, proposed that the pandemic was maybe that opportunity to reconnect with the soul. In his roughly three decades of working in the film industry, he claimed, it was a privilege, he hadn’t afforded himself. This was the time to recollect thoughts, maybe look for that inner voice and calculate what it was trying to tell you. Art, the veteran art director argued, was merely an expression of that voice. Desai, who passed away at the age of 57, by suspected suicide, erected some of the most iconic sets to ever be conceived in the history of Hindi cinema.

Desai started his career with Govind Nihalani’s Tamas (1988). He then worked on Discovery of India, a mammoth episodic project that set him up for a career in manufacturing marvels out of history. Desai’s first major collaboration on a film set came with Vidhu Vinod Chopra’s 1942: A Love Story. Coincidentally and perhaps poignantly, Desai’s last Instagram post harks back to the days of creating the set for an enchanting musical, set in the hills of Dalhousie in Mumbai itself. It’s just the kind of job where Desai and his ilk came in. To exact the improbable from a mere whim, to deliver, tangible structures from the breeding ground of sincere ideas. The sets of Chopra’s film, a make-believe place from a bygone era, echoed that magical allure that would become a Desai signature.

By the time Ashutosh Gowariker approached Desai with the prospect of fashioning an entire village in the middle of nowhere, the art director had built a reputation of sorts. Period films suddenly became relevant after Lagaan’s unprecedented success. Desai’s next big accomplishment, and possibly the collaboration that earned him plaudits the world over, was his work with Sanjay Leela Bhansali on Devdas. Exotic, extravagant, glossy and at times even imposing, Devdas’ set design, emerged from the mutual aspiration of two collaborators who accentuate a tragic love story, with the emotive influence of its opulence. The film’s grandeur contrasted the inner deprivation of the characters; the rich, decorative, and painted feel of it all adding to their burdens. In his lecture, Desai recalls how the obsessive detailing on the set overshot the budget. “Even a character as small as Paro had a huge haveli. So everyone else’s haveli had to become bigger,” he says, somewhat bemused.

While creativity can be and mean many things, an art director is made by his mistakes. Only by diving into the anatomy of materialism, finding the right mix of science and magic, jugaad and jaadu, can you really arrive at a point where art, its most woke ideas, can meet acceptable solutions. Art direction isn’t problem-solving all the time, but to a filmmaker’s ethereal vision, the art director adds the first and final touch of material form. A film set, once the most celebrated possession of studios, is only as good as an art director’s resourcefulness, his understanding of both the material and the immaterial. In a sense, he exists on the border of imagination and realization.

Over the last decade, our cinema has comfortably shifted out of studio spaces. New age stories are now set in the dusty lanes of suburban, small-town establishments, as opposed to the fabricated locations of periods from history. Digital technology, which Desai actually supported, has replaced the need for material presence. Eras can be grafted, texture imported, and periods plastered onto green screens. Most people don’t have the patience or the madness of a Bhansali to go out and built tangible experiences from scratch. The studio now exists as an extension of its technical grasp, as opposed to its geographic spread. Cinema has quite simply moved onto faster solutions. Solutions that Desai believed were imminent and unavoidable, but also something that could be learned. His lecture he began by talking about the Ajanta-Ellora caves, and his acute understanding of why they are a feat of artistic management, as much as they are a celebration of artisanal skill.

In 2004, Oliver Stone came to India to scout studio spaces to shoot the mammoth Alexander. He connected with Desai but couldn’t agree on a space that looked like it could support his standards. A year later, Desai opened ND Studios in Karjat, a place that he wished would reproduce the scale of a Warner Bros, as the studio lot where entire spectacles could be shot and finished. Here at ND Studios, Desai also wanted to train people in precisely the kind of skill that a movie set requires from time to time. “I can build a palace in a week,” he claimed, in an interview shortly after the launch. Sets that would be dismantled in days or months. The cinematic grandeur and splendour that his palatial cinema stood for will, in contrast, last forever.

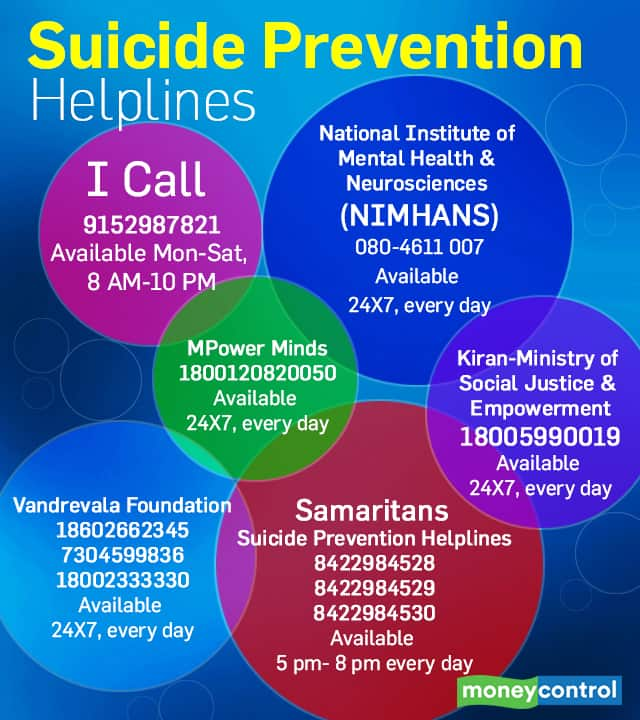

Suicide prevention helplines.

Suicide prevention helplines. Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.