In the history of financial diplomacy, July 21, 2005, just can't get respect.

More's the pity: Events that transpired on that day, when Beijing severed a long-standing link to the dollar, and the reception in Washington and Berlin, laid the ground for one of the sagas playing out in the $7.5 trillion-a-day foreign-exchange market.

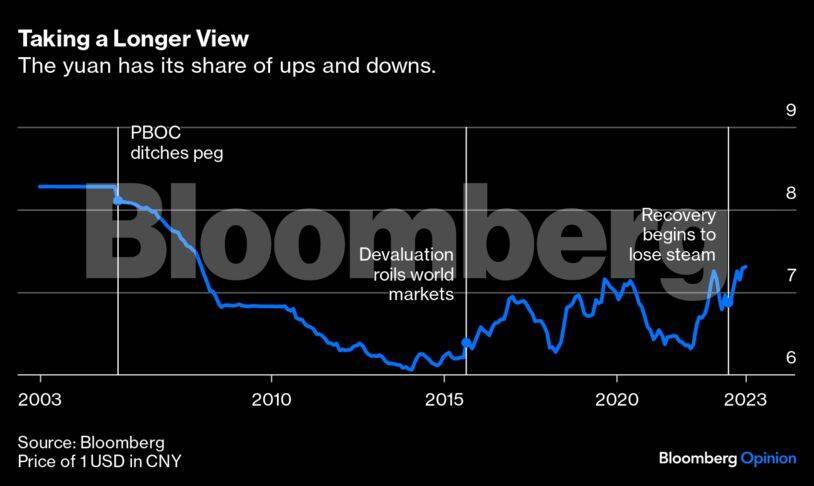

They also go some way to explaining why China's recent efforts to restrain the yuan’s decline have been cast in dramatic language. Trading levels are described as lines in the sand, some shaded red. Officials are said to have vowed, threatened and even cajoled traders into scaling back bets on a weaker currency. The yuan has lost about 5 percent against the dollar this year. On Tuesday, it approached the limit of the range in which authorities will permit it to fluctuate — a rare occurrence.

The People's Bank of China is alternately depicted as ready to relent or stand firm. Isn’t it normal for a currency to retreat when growth is languishing and interest rates are being cut? The PBOC has many tools to guide investors. It deploys them, especially when it wants to make a point, like “slow down, just take it easy.” It’s a nuanced position that risks being blown off. In the almost two decades since the hard peg was jettisoned, the yuan has moved up and down, along with perceptions of the economy's vigor.

You would be forgiven for not recognising, for instance, that the yuan had strengthened significantly in the intervening years. The problem may, at least partly, be one of perception. Which brings us back to that summer day in 2005. The PBOC declared that it was finally scrapping a firm rate of 8.3 per dollar. The move, which saw the yuan shift to being managed against a basket of currencies, included a one-time revaluation. The transition had been a long time coming. Pressure from the US and Europe — seeking to curb China's export strength — was intense.

The step was welcomed in the West and heralded as the beginning of a liberalisation that would surely lead to a stronger currency. “China's full implementation of its new currency regime will be a significant contribution toward global financial stability,” John Snow, then secretary of the US Treasury, responded. Hans Eichel, the German finance minister who pushed for an adjustment, said Beijing complied with Group of Seven demands. Malaysia chose the moment to re-float the ringgit, seeking a buoyant return to the market.

A slightly more flexible FX regime was code for a less cheap yuan. Of course, the move also had to benefit China. In addition to staving off trade penalties, the PBOC got more leeway to pursue an independent monetary policy.

With the benefit of contemporary perspective, something big was obscured: The yuan wasn't a one-way street and, like all currencies, it would have stretches of ascent and depreciation. That was a concern for the future. Back in 2005, China was enjoying tremendous rates of growth after joining the World Trade Organization. Gross domestic product increased more than 11 percent that year, almost 13 percent in 2006 and about 14 percent in 2007. An economy in the doldrums, and a currency that reflected that, wasn't in the vocabulary. This was a failure of imagination.

The situation was far from ordinary in another respect. China wanted — and still does — the yuan to be taken seriously. But surrendering control was never on. The PBOC set a daily trading band and guided traders to its sweet spot via a morning “fix.” State banks are active buyers or sellers, sometimes under direction. Officials hike or slice the amount of FX reserves lenders are required to keep.

So with the yuan now under pressure, it’s easy to characterise transactions as a tussle. The PBOC isn't letting the invisible hand go where it fancies. Authorities would be comfortable with a gentle decline, but that doesn’t appear to be what the market wants. The central bank has been digging in its heels, setting the daily fix in the vicinity of 7.15 to the dollar, while the yuan has tended to end the day around 7.3.

Clearly, the PBOC has affection for 7.3. It's unlikely to hold forever. Does it cede the ground gradually or throw bears off guard by backing off suddenly? A repeat of 2015, when China devalued suddenly through the morning fix, would be undesirable. That retrograde action threw global markets into a flux and, ultimately, led the Federal Reserve to postpone tightening it had projected for the middle of the year.

The bank's tactics led Wei He, an economist at Gavekal Dragonomics, to consider in a recent note whether a de-facto peg has been re-instituted. And, if so, what that has in store:It would probably take another sizeable negative shock to the economy, not just more of the same, to convince the PBOC to give up its defense of the currency and re-set the fixing at a weaker level. Such a shock could potentially come from the implosion of more property developers, the failure of a domestic financial institution, or an event that causes a fresh increase in China tensions. But for the moment, the changes at the margin in the economy are becoming more positive, with property policy easing and the electronics cycle, a key driver of exports, turning up.

The PBOC will probably try to muddle through. That isn't a terrible path. Just imagine if the yuan hadn't weakened this year, along with the string of disappointing economic reports. We might really be in trouble. In that sense, let's embrace a weaker currency, albeit it not one that weakens forever.

Daniel Moss is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian economies. Views are personal and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Credit: Bloomberg

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!