I used to be a great fan of action thrillers, and the bigger, the better. But as I have aged, I have begun to find violence and gore rather taxing. I now prefer feelgood films and when I can’t find something new to watch, I go back to old favourites. Among these comforting staples are the films that the late Basu Chatterji made in the 1970s. So I read Anirudha Bhattacharjee’s recent biography Basu Chatterji And Middle-Of-The-Road Cinema with interest.

Vintage; 320 pages; Rs 699

Vintage; 320 pages; Rs 699I am certainly not a Basu Chatterji expert and did not even know that he had made so many films. Conversely, it had slipped my memory that a couple of films I had watched many years ago were directed by him. My abiding memory of Chatterji is of the sensitive, gently funny and heartwarming films he made in the first decade or so of his career, which put the “common middle-class man”—often played by the young Amol Palekar—at their centre.

Chatterji made tragic films too, but his legacy is the common-middle-class-man film. Other Hindi film directors had of course featured middle-class heroes before Chatterji, notably fellow-Bengali Hrishikesh Mukherjee, but in their films, the common-man heroes would invariably be facing some heroic or tragic task. Their stories were actually very uncommon.

In Chatterji’s films, the hero lives an entirely mundane life, is not in any way bright or talented as defined by a meritocratic society, and has no ambitions beyond winning the girl he has fallen in love with, a better apartment to stay in with his wife, a promotion and nice pay raise in his clerical job.

No one had done this before in Hindi cinema. And the films connected with large masses of Indians who, consciously or unconsciously, led, in Henry David Thoreau’s words, “lives of quiet desperation”. They rooted for the hero—and the heroine—because they saw themselves in these people and when it all ended happily, they left the theatre with a smile on their faces. They felt reaffirmed about their identity and the unmonetizable value of their small dreams.

Looking back, Chatterji’s early films were quite revolutionary, though quiet and understated.

As Bhattacharjee puts it, “(Chatterji), with his ear to the ground, identified with the ordinariness of people and circumstances and told their story in a manner not tried before. It was devoid of gimmicks, but had a lot of heart… People who were becoming progressively tired of the excesses in the name of entertainment loved (his films).”

I have been using the term “common-man-film” because that is how Chatterji’s work has always been described by critics. Yet, as Bhattacharjee points out in his book, the “common women” in the films are as important as the men, and often smarter and more complex than the men.

For instance, Rajnigandha (1974), one of Chatterji’s finest and most enduring films. Bhattacharjee points out that this story of a young woman torn between two men was a boldly feminist tale for its times.

Of course, love triangles had been a popular theme in Hindi cinema for decades, but all the films were basically shallow and patriarchal—copious tears, self-sacrifice and often suicides by the men who lost out. It was pure mush on a grand scale.

Rajanigandha (Image from the book)

Rajanigandha (Image from the book)Chatterji’s film was radical, though it spoke softly. It said that it is absolutely all right for a woman to be in love at the same time with two men. And the film ends ambiguously—she still has not resolved her dilemma. Rajanigandha offers no closure, unlike any Hindi film made till then. Yet, so refined is Chatterji’s touch that the audience does not grudge this at all, and just wants her to be happy, willing to accept whatever choice she makes.

This low-budget film by an unknown director with equally unknown actors, became the first film ever to win both the popular choice and critics’ Filmfare awards. In hindsight, this reflected a seismic change that was occurring in urban Indian society—a liberalization of attitudes and mores. Chatterji was perhaps the first Hindi filmmaker to spot this.

Among his other films of that period, one can watch Chhoti Si Baat and Chitchor (both released in 1976) any number of times even today. They remain fresh and fun, reminding us of a happy innocence that all of us may have lost.

An interesting aspect of these movies is that there are hardly any bad people in them. Even the Asrani character, Amol Palekar’s rival in love, in Chhoti Si Baat, is just a preening idiot—you can’t hate him, you can only laugh at the man. In Chitchor, the Germany-educated engineer gracefully accedes to his underling—in fact, makes sure that he gets the girl.

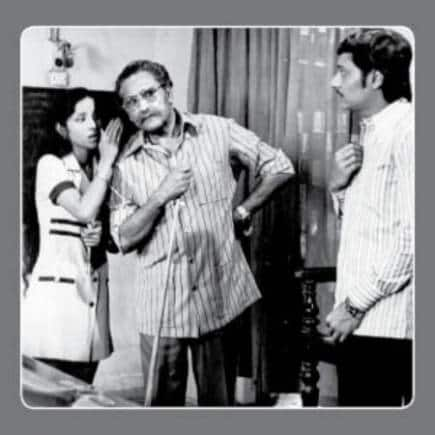

Chhoti Si Baat (Image from the book)

Chhoti Si Baat (Image from the book)Even when there are some bad folks, like the crooked auto garage owner in Chhoti Si Baat, they get their rightful comeuppance, often in a hilarious manner.

Last week, I was watching a hospital drama on a streaming service which I enjoyed a lot. Out of curiosity, I checked out the reviews it had received. It seemed to have been universally panned in the US, and the main grouse the critics had was that all the doctors in the show were good people! But what is wrong with a story that does not have any villains, when no so-called intellectual has ever found fault with books and films that have no “good” men? These opinions tell us more about the critics than about anything else. The paying public does not seem to have cared. The third season of the show has dropped recently.

Bhattacharjee is one of the most hard-working and meticulous Indian film historians I have ever read. His books on Sachin Dev Burman, Rahul Dev Burman and Kishore Kumar are unlikely to have any serious challengers in the near future. He is also brutally fair, unlike many other biographers who are in reality hagiographers. Bhattacharjee has no hesitation in saying that Chatterji made quite a few poor films too.

He also details the many minor flaws even in the best of Chatterji’s work. Throughout his career, Chatterji was shoddy on details. There are frequent glaring continuity errors—like the characters’ clothes changing from shot to shot within the same scene. The biggest example of the director’s carelessness is Ek Ruka Hua Faisla (1984), a remake of the Hollywood classic Twelve Angry Men (1957), about the dynamics within a jury in a criminal case. The film is set in the 1980s, but the jury system in India was abolished in the 1950s, a fact that Chatterji could hardly not have known.

I would certainly not rate Chatterji among the top 10 filmmakers in independent India. Yet, as Bhattacharjee’s book shows, he was a pathbreaking auteur who created a whole cinematic genre in Hindi, real and down-to-earth films with zero bombast, zero melodrama, zero preaching, about real and down-to-earth people and their modest hopes. That is a great achievement for which this naturally self-effacing man who never courted media publicity has not received due recognition. I hope this book helps in that necessary correction of history.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.