Ivan Glasenberg always preferred to buy rather than build as he assembled Glencore Plc. “This company doesn’t trust greenfield projects,” he said in 2017, four years before his retirement as chief executive officer. In two decades, he had created the world’s fourth-largest mining company by buying others, from miner group Xtrata to grain trader Viterra.

Now is the moment for another giant acquisition. The global energy crisis has delivered the company a one-off opportunity to transform itself.

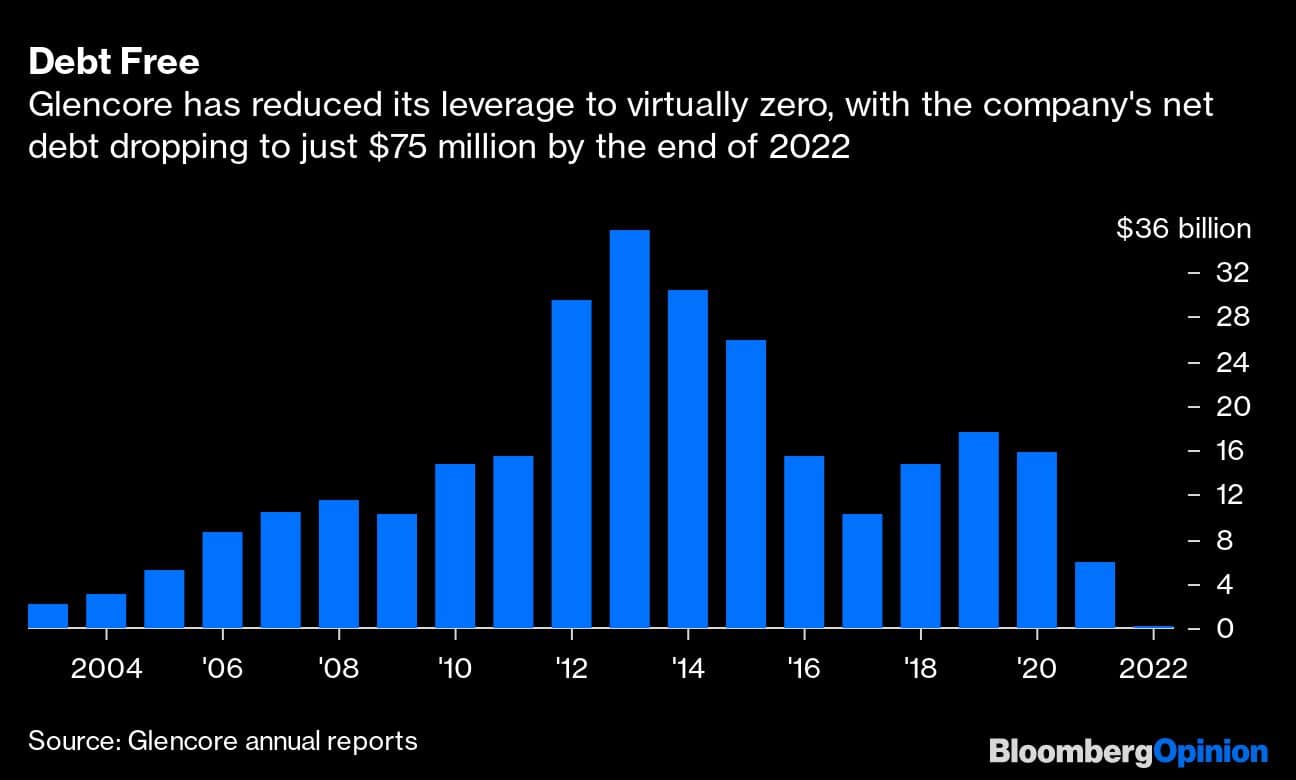

Thanks to eye-watering coal profits, Glencore has its strongest balance sheet since going public more than a decade ago. At the end of 2022, its net debt stood at just $75 million, down 99 percent from a peak of $35.8 billion at the end of 2013. Last year, its adjusted core earnings jumped 60 percent to a record $34.1 billion. Half of that — $17.9 billion — came from mining coal.

Even with a self-imposed limit of $16 billion in net debt for an acquisition, Glencore has a war chest now to pursue a serious target. Having settled its bribery and money-laundering troubles with the US Department of Justice and other authorities, paying more than $1 billion in penalties, it can also use its stock for acquisitions. In short, Glencore has money to spend. If not now, when?

Glasenberg’s successor, Gary Nagle, is fully aware of the opportunity and shows the same inclination for dealmaking. In a meeting with investors last week, he said in rapid succession “we want to do M&A”; “it’s part of our DNA”; “a lot of this company has been built on the back of M&A.”

But Nagle insisted, as his former boss did, that he wouldn’t make a purchase for the sake of it. It has to be the right deal at the right price. And right now, neither is available.

In the meantime, the 47-year-old executive, who took the post in 2021, says the commodity miner-cum-trader has plenty of growth potential on its own, by both expanding existing mines – so called brownfield projects — or building new ones — greenfield projects. But without extra tonnage – and none is coming before 2025 -- earnings can only grow via higher prices. And that’s betting on another energy crisis lifting coal to the stratosphere. Coal prices remain high by historical terms, but they have already plunged in early 2023, halving in the past 45 days

Glencore has told investors it has four big projects — in Chile, Peru, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Argentina — that would allow it to cash in if copper prices rise. But rather than build, it can buy.

Let’s start first with what Glencore isn’t interested in. The company sees value in small deals in aluminum — say in the $1 billion-apiece area -- but it’s not interested in acquiring a large aluminum company like US-based Alcoa Corp.

Copper should be the preferred target. About two years ago, Glencore held detailed merger talks with Canada’s Teck Resources Ltd, which ended without a deal. Still, buying Teck makes the most sense for Glencore. The synergies are obvious. Teck is a major shareholder of the Quebrada Blanca copper mine in Chile, which lies just a few miles from Glencore’s own Collahuasi mine. Teck owns a stake in Peru’s Antamina copper mine, in which Glencore also has a major interest. And Teck has a coal division that would fit with Glencore’s own one. The Canadian miner is worth $22.5 billion, plus debt, while Glencore’s market capitalisation is nearly $80 billion. Free of net debt, Glencore can swallow it.

If only Teck was for sale. The company, controlled by the Keevil family under a dual-share structure, has other plans. If the Keevils ever put it up for sale, it’s likely to attract the kind of bidding frenzy Glencore tries to avoid. Even so, having tried once, Glencore surely will try again. And it wouldn’t be the first time the company bid in an auction. It did so with Viterra, beating US rival Archer-Daniels-Midland Co, for the Canadian grain trader.

Beyond Teck, the number of attractive targets shrinks rapidly. US-based copper miner Freeport McMoran Inc is too expensive. Canada’s First Quantum Minerals Ltd is fighting with Panama’s government for control of a key asset. Others appears too small to move the needle.

Glencore executives often sound frustrated with their rivals’ reluctance to sell. Ego prevents deals, or so the thinking goes. They aren’t wrong. But what really stops deals is money. Put a good offer on the table, betting on a higher-for-longer copper price, and there’s a good chance the egos surrender to the deal. And today, for the first time in a long time, Glencore has the cash to do so.

Javier Blas is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy and commodities. Views are personal and do not represent the stand of this publication.Credit: BloombergDiscover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.