Every year, for some nine days, the South Mumbai neighbourhood of Kala Ghoda comes alive. The annual Kala Ghoda Arts Festival that concluded its latest edition just last month, started in 1999 and has grown into an important event that kicks off the city’s cultural calendar. But even as thousands of patrons visit the festival, many do so without realising the history that surrounds them.

To be sure, you need to merely look around you to realise that you are in a historic precinct. Stand at the triangular parking lot and you’d be facing a row of majestic buildings starting with the National Gallery of Modern Art to your left and ending with Army Navy Building right in front of you.

The Army Navy Building is perhaps the most recognisable, being home to the flagship store of the clothing brand Westside. Quite like its neighbour, the adjacent building that houses the David Sassoon Library is built using Malad Stone, quarried from the now-bustling suburb of Malad.

Look around a little more and you’ll see the Jehangir Art Gallery, arguably the most prestigious one in the city and among the most well-known galleries in the country, and the dome of the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya or as the old timers would remember it, the Princes of Wales Museum.

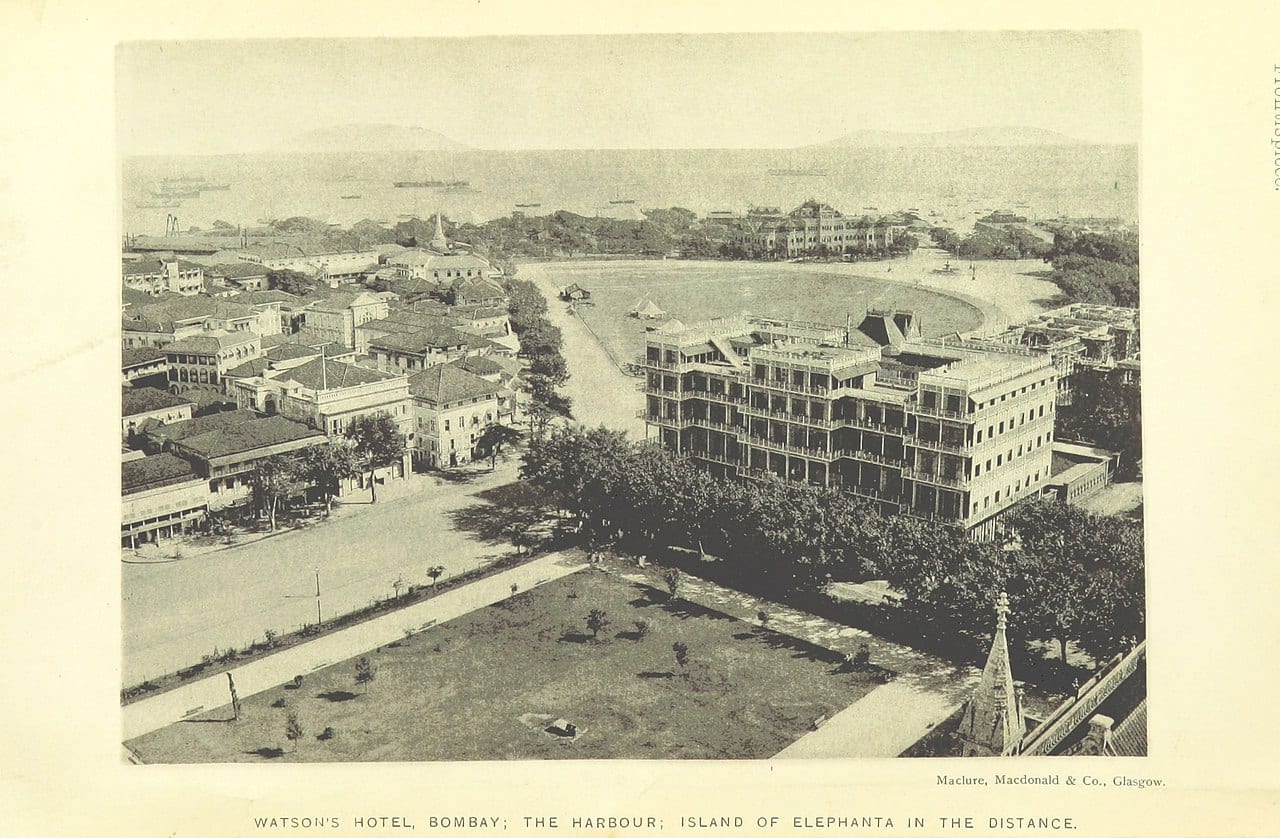

Should you find yourself in Kala Ghoda today, you will also see a dilapidated building at the signal that’s undergoing renovation, seemingly forever. But what may be an eyesore to you is actually India’s oldest surviving cast iron building that’s being restored to its original glory following years of appeals and a damning structural audit report.

But this is merely what you see.

These buildings and the neighbourhood around them, hold a treasure trove of stories that have shaped the city and the nation itself. The dilapidated cast iron building was once home to Watson’s Hotel, a luxury hotel which was the venue of India’s first movie screening in 1898. Urban legend also suggests that on being turned down from Watson’s Hotel on account of being Indian, the industrialist Jamsetji Tata vowed to outdo it and built the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel.

Also read: Insider’s travel guide to Mumbai: Seaside cities are more welcoming than landlocked onesBut Tata’s connection to the street and the neighbourhood goes back long before it got its current name. He studied right here at Elphinstone College. As did Dadabhai Naoroji, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, and Babasaheb Ambedkar, among many other luminaries.

Esplanade Mansion, previously Watson's Hotel, is India's oldest surviving cast iron building. (Photo: British Library via Wikimedia Commons)The Wayside Inn: Where the Indian Constitution was written

Esplanade Mansion, previously Watson's Hotel, is India's oldest surviving cast iron building. (Photo: British Library via Wikimedia Commons)The Wayside Inn: Where the Indian Constitution was writtenB.R. Ambedkar, the father of the Indian Constitution, wrote large parts of the Constitution sitting at table no 4 of The Wayside Inn. A café that has been long shuttered was the meeting point of intellectuals, artists, and creative folks alike. The late Parvez Patel, who passed away merely months ago, would likely have told you of the time Ambedkar would walk into his family’s café and be found bent over the table writing on foolscap sheets with a row of pencils, an eraser, and pots and pots of tea for company.

The Wayside Inn was also where the legendary Russi Karanjia, Dinkar Nadkarni, and Benjamin Horniman would get together to discuss the newspaper they were birthing: The Blitz that pioneered tabloid journalism in India.

Benjamin Horniman was, of course, the Bombay-based British journalist, after whom the nearby Horniman Circle has been named. But you would likely remember The Blitz and its editor Karanjia from the 2016 movie Rustom. The movie is based on a real-life story of the 1959 court case against Indian Naval Commander K.M. Nanavati who was accused of murdering his wife’s alleged lover Prem Ahuja. Karanjia’s terrible portrayal as a sleazy journalist sniffing around for a story notwithstanding, the movie gets one fact right, the case made The Blitz a force to reckon with. Karanjia (or Mr Karanjia to his juniors), a far more erudite man than what is shown in the movie, would go on to groom an entire generation of Mumbai journalists.

The Wayside Inn wasn’t the only meeting point for the city’s creative and bohemian folks; just a few paces down the road was Chetana.

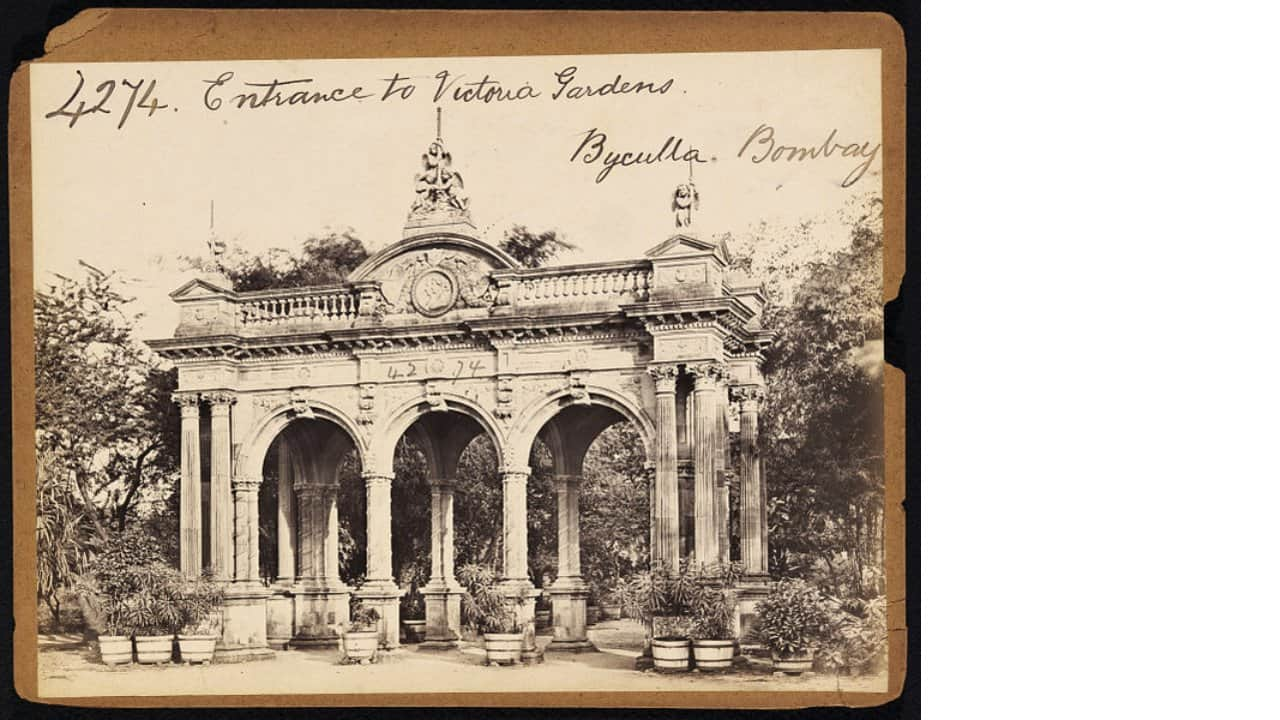

The original Kala Ghoda statue is at Victoria Gardens, now called the Veermata Jijabai Bhosale Udyan. (Photo: Albumen print by Fracis Frith, via Wikimedia Commons)Birthplace of Bombay Progressive Artists’ Movement: Chetana

The original Kala Ghoda statue is at Victoria Gardens, now called the Veermata Jijabai Bhosale Udyan. (Photo: Albumen print by Fracis Frith, via Wikimedia Commons)Birthplace of Bombay Progressive Artists’ Movement: ChetanaIt is easy to dismiss Chetana as just another vegetarian thali restaurant. But when it started in 1946, just a year before India’s independence, Chetana was a creative hub. Frequented by poets and artists, writers and filmmakers, Chetana was a 2500-sq ft cocoon for the city’s creative folks. The space included a bookshop, a dance studio that offered space for poetry readings and cultural meetings.

M.F. Husain, S.H. Raza, Akbar Padamsee, F.N. Souza and every other artist that’s today powerful enough to go by one name, exhibited their work here for the first time. No surprises then that Chetana was also where the Bombay Progressive Artists’ Movement was born.

The filmmaker Shyam Benegal famously called Chetana the only constant ‘the Dhruva (North Star) on charming Rampart Row.’

Chetana has had to evolve to survive but even its current avatar – as a mainstream veg restaurant – is a reflection of the city’s cultural landscape.

But how did Kala Ghoda get its name?If you grew up in Bombay of the 1970s, '80s, '90s or even the noughts, you were bound to wonder how the neighbourhood got its name. Logic would dictate that there would be a statue of a black horse somewhere after which Kala Ghoda would have been named. Yet there wasn’t. A story I grew up hearing was that the precinct itself looked like the mouth of a horse when seen from above. This was, of course, rubbish.

Albert Sasson, son of David Sassoon of the nearby library fame, commissioned the creation of a statue of King Edward VII (who was at the time Prince of Wales) with the intent of placing it in the square in his honour. Inaugurated in June 1879, the statue featured Edward riding a horse. Before long, the ruler was forgotten, and the neighbourhood derived its name from the majestic beast upon which he sat.

The statue itself remained there for almost a century until 1965, when in a wave of nationalistic fervour, it was swept off from its place of prominence. For a little over half a century, the neighbourhood remained horseless. It wasn’t until 2017 that the Kala Ghoda Association, which runs the festival, commissioned a new statue of a similar looking horse, albeit without the rider. This statue is the one you see today and is officially called the Spirit of Kala Ghoda.

Spirit of Kala Ghoda statue (Photo via Wikimedia Commons)So where is the original Kala Ghoda statue?

Spirit of Kala Ghoda statue (Photo via Wikimedia Commons)So where is the original Kala Ghoda statue?King Edward VII was the son of Queen Victoria and the longest heir-apparent to the British throne until his great-great grandson Charles broke his record. While Charles was heir-apparent for over 70 years, Edward (or Bertie) was the king-in-waiting for nearly 60. Victoria never gave him any real powers and Bertie was relegated to ceremonial duties.

When his statue that gave Kala Ghoda its name was removed from the precinct in an attempt to wipe out the colonial markers, it was moved to the city’s zoo, or the Veermata Jijabai Bhosale Udyan. When he was moved, though, the zoo was called Victoria Gardens, after his mother Queen Victoria. And so it is that even in his death as in his life, Edward VII remains under the shadow of his overbearing mother.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.