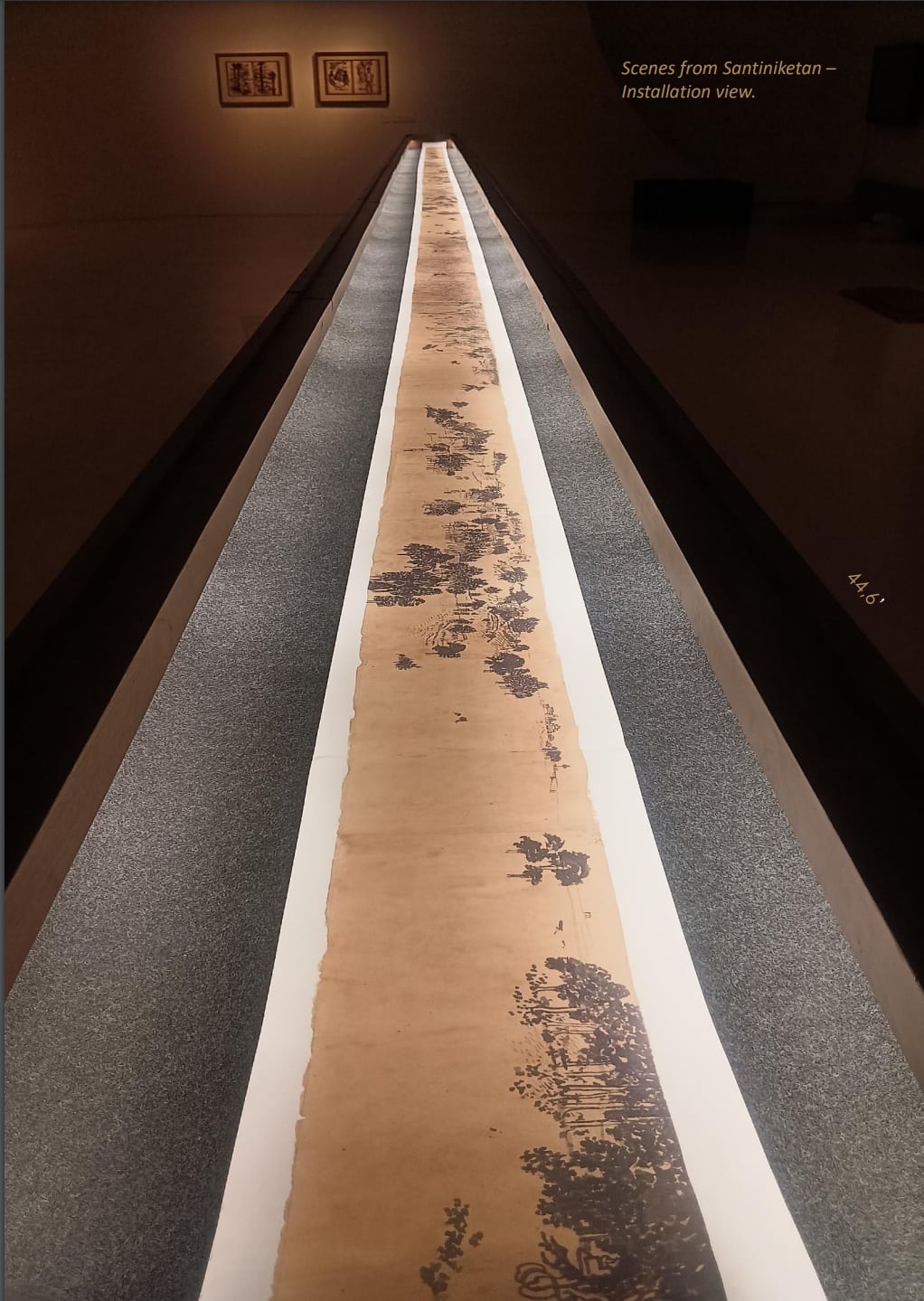

A century-old, 44.6-plus-feet scroll painting inscribed 1924 by the artist Benode Behari Mukherjee, who was filmmaker Satyajit Ray’s teacher at Santiniketan, is on exhibition before the public for the first time. Gallerist and archivist Rakesh Sahni, who runs Gallery Rasa in Kolkata, acquired the scroll about five years ago. Mukherjee had given it or sold it to the painter Sudhir Khastagir, who was also a student at Kala Bhavan, Santiniketan, under Nandalal Bose. The scroll is made on “thin paper”, said Sahni, joined together to create this long work. The join marks are visible as vertical lines on the scroll. “If it was thicker paper, it would have probably creased, like even chart paper does,” Sahni said on the phone. “It is luck that it was such thin paper. But this apart, the scroll took months of meticulous restoration before we could even think of showing it.”

Displayed in a very long and slender rectangular case designed specifically for the scroll, ‘Scenes from Shantiniketan’ offers a cinematic view of the landscape and seasons of Santiniketan—a rural, and at the time, wooded and slightly wild quarter that became the home for Rabindranath Tagore’s university-school complex founded in 1921. I say cinematic rather than panoramic because the work changes perspective. At the start is a ground-level view featuring the lower trunks and vine-like hanging roots of a thicket of trees with a small hunched figure seated in the cave-like canopy. The work then moves to whole trees in a wooded area, as if you are walking amid them and looking up in wonder; and then to an overhead, bird’s view of paddy fields with small settlements of huts adjacent to them and foot-worn pathways leading away. The impression is of a camera moving across the landscape, on the ground and travelling up and down, zooming in and out to capture the setting in detail and overview. Mukherjee uses space as a transitioning device to change perspective. The effect is once again cinematic: his use of space is similar to the use of editing cuts in cinema to transition from one sequence or scene to another. In Chinese scrolls, mist is used as a transitioning device, curator R Sivakumar’s text notes.

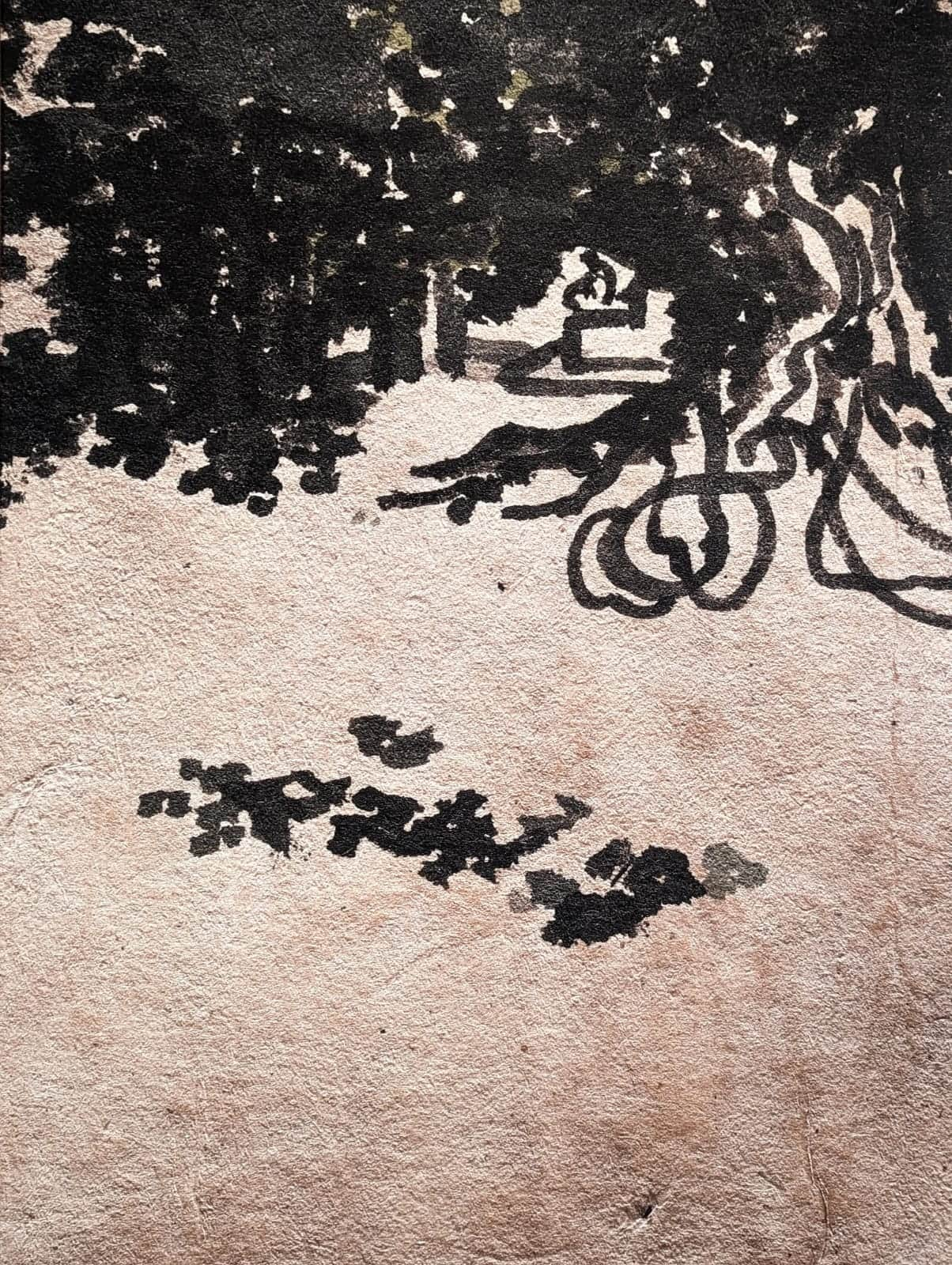

A segment from the opening section of the scroll, Scenes from Santiniketan. Note the hunched figure on the steps surrounded by the canopy of the trees.

A segment from the opening section of the scroll, Scenes from Santiniketan. Note the hunched figure on the steps surrounded by the canopy of the trees.There is, furthermore, a change of seasons along the scroll. We start in what feels like late winter or what passes for spring in Bengal with leaves on the ground. Then, summer marked by the unmistakeable silhouette of a bulbul, then the monsoon where the mostly black and muted red work takes on a verdant green for the paddy that is readying for harvest. By the time we near the end of the scroll, it is what looks like the beginning of winter, when nature starts to retreat, in the bare, leafless, tablet-like Khoai terrain of Birbhum.

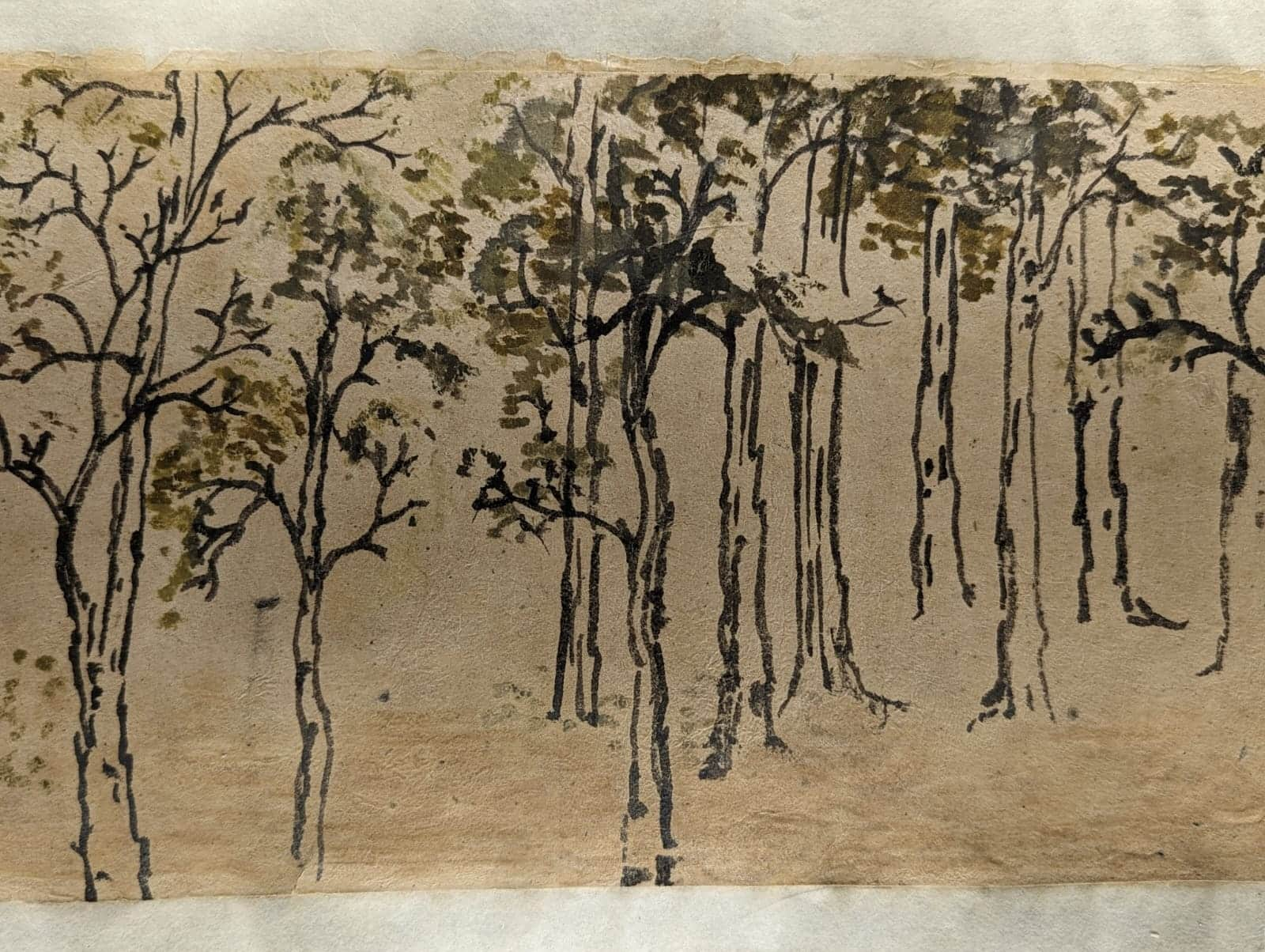

A section from Scenes from Santiniketan: Can you spot the bulbul?

A section from Scenes from Santiniketan: Can you spot the bulbul?These details are brought to our attention with audio notes, because while the scroll is long, it is small in width. Only 6 inches high, about the size of a child’s notebook. The details are minute, most of these would escape the viewer without the excellent audio notes. Sivakumar has divided the work into 10 sections, using Mukherjee’s space transitions as cues. Each section comes with an audio note in English. The curation is excellent, with intelligent unintimidating use of technology, and the notes, both audio and text, are accessible and clear and often biographical, which works as a wonderful point of interest. Almost as if a central character is taking us through the Santiniketan of 1924.

A partial view of the scroll Scenes from Santiniketan on display at the Kolkata Centre for Creativity that offers a sense of the length of the work.A Young Man With Severely Limited Vision

A partial view of the scroll Scenes from Santiniketan on display at the Kolkata Centre for Creativity that offers a sense of the length of the work.A Young Man With Severely Limited VisionMukherjee would have been 20, if the inscribed date is correct, at the time of painting this scroll, only five years into his training in art. He joined Kala Bhavan when an eye-specialist in Calcutta (as it was then called) gave permission for him to study art at the age of 15, Satyajit Ray narrates in his documentary The Inner Eye. The 21-odd minute film, available on YouTube, plays on a loop in the exhibition. Mukherjee was born blind in one eye and severely myopic in the other and was, hence, not able to pursue an education in the normal course. But he had a gift for drawing, like all his five brothers, and drew from a young age. He was admitted to Patha Bhavan, the school at Santiniketan, three years before he joined Kala Bhavan.

From the brochure published for the exhibition Scenes of Santiniketan, published by Gallery Rasa and the Kolkata Centre for Creativity

From the brochure published for the exhibition Scenes of Santiniketan, published by Gallery Rasa and the Kolkata Centre for CreativityThe minute hunched figure at the beginning of the scroll is likely a representation of himself, the show’s note says. At the start of the show, we see two reproductions of Mukherjee’s self-portraits—in both, he has the hunched bent-over posture that we see in the first section of the scroll. “In Santiniketan, one had got used to the sight of him hunched over his painting, brush poised over paper for that sensitive precision of stroke that would set the seal of distinction upon it,” Ray says in The Inner Eye. Ray was a student of his when he studied drawing at Kala Bhavan. Before he became a filmmaker, Ray made a name for himself as an illustrator and book cover designer with Signet Press. Indeed, throughout his life, Ray continued to draw—for his legendary story boards, for his scripts and his Feluda and other books for young adults.

A screengrab of Mukherjee in his trademark hunched pose, painting, from Ray’s The Inner Eye.

A screengrab of Mukherjee in his trademark hunched pose, painting, from Ray’s The Inner Eye.The scroll proceeds from right to left, the opposite of traditional scroll paintings such as patachitra in India, which go from left to right. This is in the East-Asian style, the curator’s text reads. Mukherjee’s deep interest in the physical landscape is also an East-Asian influence, Sivakumar has pointed out. Indian art, both traditional and modern work, has been invested in mythology. Nature is an important element in Indian art, but a singular focus of the landscape did not exist. For instance, the nomenclature of the Pahari school may suggest an inclination towards nature, the mountains, but the works are mainly devoted to depictions of Krishna. Mukherjee is the first major landscape painter in India, alongside his teacher Nandalal Bose. In fact, this particular scroll predates Bose’s work on landscape, said Prof Sivakumar.

Mukherjee got an opportunity to travel to Japan in 1937. But Nandalal Bose, the ‘mastermoshai’ of Kala Bhavan, travelled to China and Japan in 1924 and brought back several books on art from these two counties, the academic and writer Swati Ganguly writes in Tagore’s University: A History of Visva Bharati 1921-1961. It was the same year that ‘Scenes from Shantiniketan’ is dated. Right from the start, even before Visva Bharati had opened formally, Tagore had envisaged a space were students could learn about both Oriental and Occidental art.

‘Scenes from Santiniketan’ is one of four complete scrolls by Mukherjee that survive in their entirety. Two more exist in fragments, said Siddharth Sivakumar, who works with the Kolkata Centre for Creativity team. All the scrolls, completed before 1942 and considered to mark the artist’s early career, are the subject of this show. But only ‘Scenes from Santiniketan’ is displayed in the original, the rest are reproductions.

From the brochure published for the exhibition Scenes of Santiniketan, published by Gallery Rasa and the Kolkata Centre for Creativity

From the brochure published for the exhibition Scenes of Santiniketan, published by Gallery Rasa and the Kolkata Centre for CreativityEven so, they offer a palpable sense of the desolate beauty of Santiniketan 100 years ago, when the woods were lovely, dark and ghostly. (Rabindranath Tagore’s own drawings, begun from the age of 67 around the same time that Mukherjee was making these scrolls in the 1920s, evoke a similar sense of eerie loveliness. To my mind, it is the wild, uninhabited nature of the terrain that brings out this sense of the supernatural.)

But unlike Tagore where the lines are less certain, you know you are in the presence of a master in Mukherjee’s work, most of all for how adroitly he summons a sense of three-dimensionality to his drawings. It’s magical to see three dimensions appear on a flat surface just like that, where the skill of the artist does the work of 3D glasses. The scroll titled 'Khoai' is especially stunning—an outstanding portrait of the barren, mini canyon-like formation of red laterite soil known as the Khoai that was a geographical feature of Birbhum where Santiniketan is located. Today, the Khoai is no longer visible in Santiniketan, even Ray struggled to find it when he made the film half a century ago in 1971. He used still photographs to depict the distinctive terrain, not only in The Inner Eye, but also in his earlier documentary on Tagore titled Rabindranath Tagore (1961). To see Mukherjee’s scroll 'Khoai', is to see those photographs shimmer to life.

“This documentation of Santiniketan as it was in the 1920s was a major consideration to me,” Sahni said. “We don’t have too many photographs of that time either, barring some images by E.O. Hoppe. But Mukherjee walks us through his Santiniketan.”

From the brochure for the exhibition Scenes of Santiniketan, published by Gallery Rasa and the Kolkata Centre for Creativity. “A stretch of Khoai, and in the middle of it, a solitary palm tree,” Benode Behari Mukherjee told ray. That is all. If you wish to look for my spirit, the basic essence of all that my life stands for, you will find it there. You could say, I am it!”A Wider, Richer Meditation

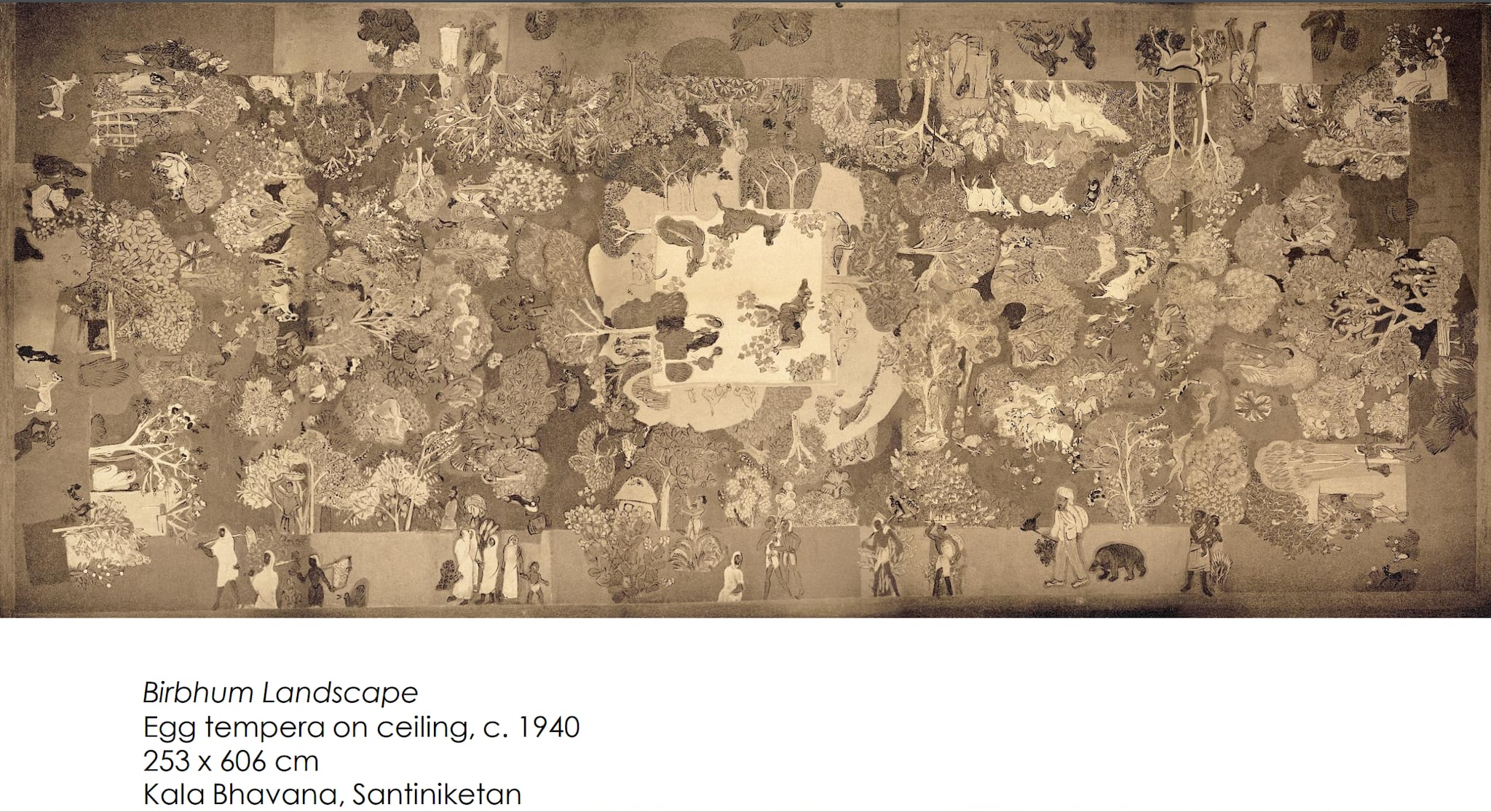

From the brochure for the exhibition Scenes of Santiniketan, published by Gallery Rasa and the Kolkata Centre for Creativity. “A stretch of Khoai, and in the middle of it, a solitary palm tree,” Benode Behari Mukherjee told ray. That is all. If you wish to look for my spirit, the basic essence of all that my life stands for, you will find it there. You could say, I am it!”A Wider, Richer MeditationThe principal feature of scroll painting, whether Indian or Japanese or Chinese, is the presence of many foci because of the size unlike the tight single focus of framed Western painting, the curator R Sivakumar has noted. Many scenes, many characters, many stories—a richer, more expansive meditation on the world, rather than a sharp focus on a particular subject. Later in his career, when he taught at Santiniketan, Mukherjee’s interest in large, complex works with multiple elements and multiple points of viewing found another medium—he was commissioned to do frescoes and murals for the Visva Bharati campus. One fresco is the ceiling of a dormitory, depicting rural life in Santiniketan, which is captured with loving care in Ray’s documentary.

Another famous mural on medieval saints in India is on the walls of the Hindi Bhavan. Cheena Bhavan has a mural about campus life, and contains, like the scroll Scenes from Santiniketan, a self-image. In The Inner Eye, Ray documented Mukherjee making another mural with tiles from Purulia. This was done when Mukherjee was completely blind, and felt his way through the work by his hands. “This is the first time where both form and spacing is a blind man’s space,” Mukherjee said about this work in The Inner Eye.

From the brochure published for the exhibition Scenes of Santiniketan, published by Gallery Rasa and the Kolkata Centre for Creativity

From the brochure published for the exhibition Scenes of Santiniketan, published by Gallery Rasa and the Kolkata Centre for CreativityMukherjee’s scrolls, made as a young artist, offer a window to his frescoes and murals—his most public-facing and likely to be his most enduring works. This year, there is news that Unesco is considering awarding world heritage status to Santiniketan. At least, one part of the honour will be for the work of Mukherjee alongside his teacher Nandalal Bose and colleague Ramkinkar Baij. The works of all three adorn the campus of Visva Bharati—Baij with his sculptures in public spaces and Bose and Mukherjee with their frescoes and murals on the walls of the campus buildings. The trio are considered to be the most important modern artists in the Bengal school, and a formidable influence in modern Indian art alongside the Bombay Progressive Artists’ Group comprising Maqbool Fida Husain, Francis Newton Souza, Sayed Haider Raza, VS Gaitonde, to name the best-known of them.

Scenes from Santiniketan was on view at the Kolkata Centre for Creativity from 20 May – 20 June. The show is scheduled to travel to Santiniketan and Kochi after this.Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.