In this second part of this two-part series on the People’s Age, the story of the artists Chittaprosad and Somnath Hore, who carried the wounds of the famine lifelong. And editor Puran Chand Joshi, who was thrown out of the Communist Party of India in 1947.

Chittaprosad

A little before 2010, Ashish Anand, the director of DAG, located one of the last remaining copies of Chittaprosad’s book Hungry Bengal that had escaped the Raj’s confiscation. The slender volume was a sketchbook, comprising both text and drawings, of his tour of the district of Midnapore undertaken in November 1943. The book, published by the People’s Publishing House in Bombay, was priced at Rs 3. The copy Anand found lay in a bank locker of the artist’s niece, Gargi Chatterjee, in Kolkata. Chittaprosad had sent this copy to his mother by post from Bombay, the artist’s sister Gouri Bhattacharya wrote in a reminiscence titled Nihsango Paribrajak (referenced and translated in Chittaprosad Vol 1, DAG, 2011).

“Perhaps that single copy sent to my mother survives as the sole evidence of the awful terror of the times,” Bhattacharya wrote (as per the text translated in Chittaprosad Vol 1). “I have heard that five thousand copies of the book were torched due to British rage. Today I realise that probably the ruling class had no other option to do this if they had to cover up their extreme callousness, because Hungry Bengal is an extremely significant historic document. A first-hand survey report.’

In 2011, DAG (then known as Delhi Art Gallery) mounted a superb retrospective on Chittaprosad’s career in Delhi and later other cities, mounting the drawings in Hungry Bengal for the first time before the public since they were banned. Before this, it would not be wrong to say that Chittaprosad was a largely forgotten artist, remembered perhaps only in Communist and art student circles. As someone who visited that exhibition, the impact of his famine drawings on me was that of a childhood cautionary tale come to life. Like many Bengali children, I had grown up hearing the stories of the famine—masses of shrunken people crying for the starch left over from boiling rice. In Chittoprosad’s work, I encountered the faces of the people from those stories.

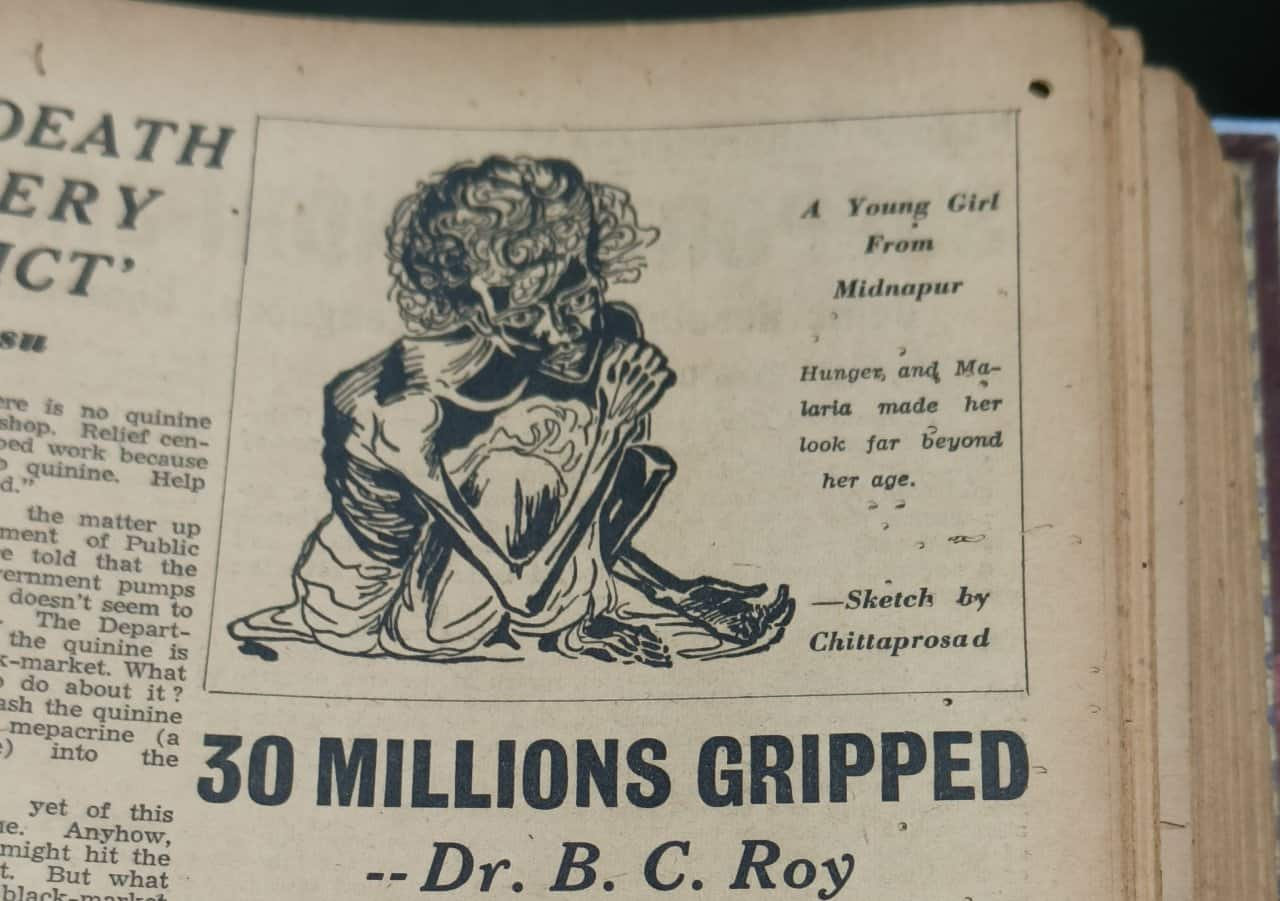

Chittaprosad’s sketches in the 10 September 1944 and 23 July 1944 editions of the paper. Archival photos of the People's Age from the Ganashakti library, Kolkata, by Sohini

Chittaprosad’s sketches in the 10 September 1944 and 23 July 1944 editions of the paper. Archival photos of the People's Age from the Ganashakti library, Kolkata, by Sohini

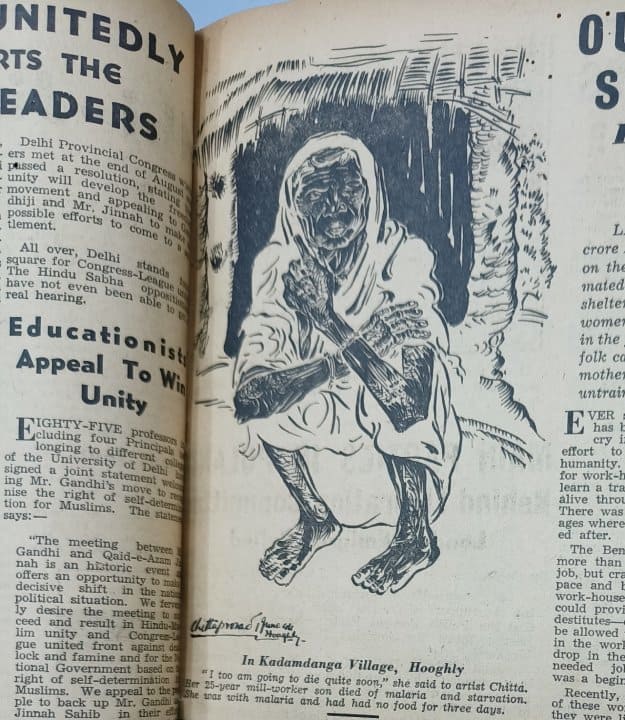

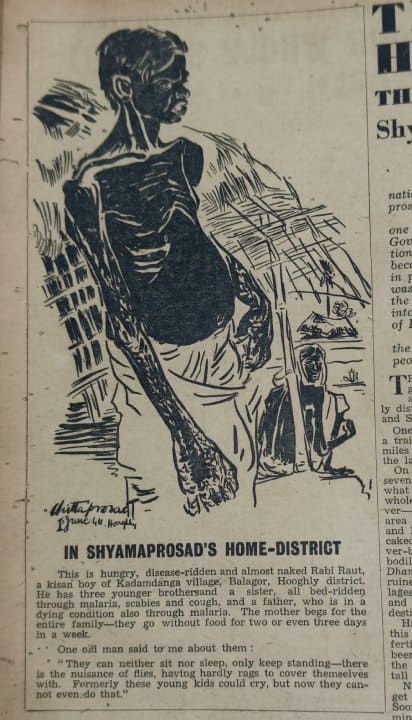

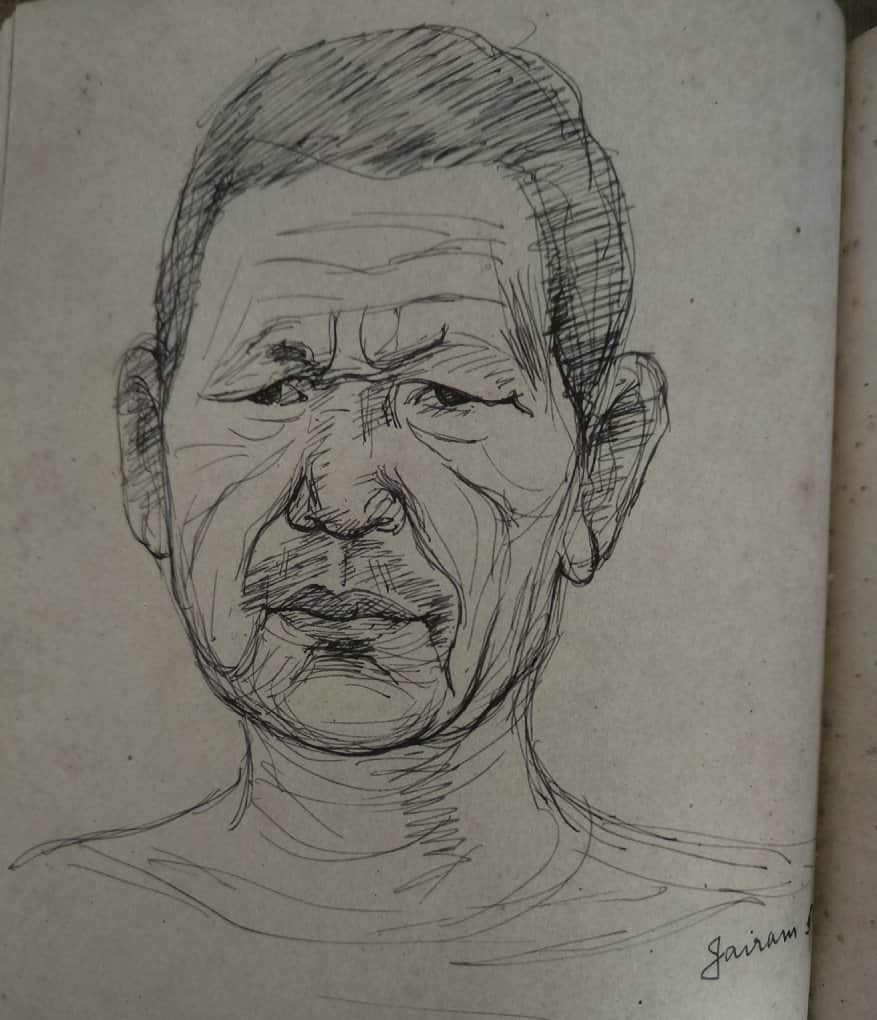

Chittaprosad’s sketches in the 26 November 1944 and 6 August 1944 (below) editions of the paper. Archival photos of the People's Age from the Ganashakti library, Kolkata, by Sohini

Chittaprosad’s sketches in the 26 November 1944 and 6 August 1944 (below) editions of the paper. Archival photos of the People's Age from the Ganashakti library, Kolkata, by Sohini

Sketched with striking use of black for the skeletal frames and distended bellies, the images were typically accompanied with detailed captions containing the full names and identities of their subjects. They are not just famine victims, Chittaprosad’s documentation implies. They are individuals with names and histories. Each sketch is a portrait.

Portraiture has been, for almost all of history, the preserve of the elite—at first the royalty and from the 16th century onward, the wealthy. The subaltern, the impoverished became subjects of portraiture only in the past 100 years or so. Chittaprosad would be among the first practitioners of subaltern portraiture, particularly in an extreme situation like 1943 where you are surrounded by devastation. Where pity is probably the first instinct, rather than the respect we give equals.

What immediately strikes us as viewers is the gaze in his portraits: tired, stoic, the eyes not entirely turned away from the viewer—creating the effect of a degree of eye contact. It is a kin of the same gaze that Janah captured in his photographs. Were they influenced by each other’s work? Or was it that their long travels across the devastated landscape of Bengal made them see in similar ways?

Somnath Hore

Unlike Janah and Chittaprosad, Somnath Hore was not commissioned by the CPI. But when he sent his drawings of the famine-affected, the Bengali edition of the paper called Janayuddha published a handful of them in 1944. Perhaps, his drawings appeared in later years too, but I could not access the archives beyond 1945.

Later, in December 1946, the CPI commissioned Hore to report on the Tebhaga Movement in Bengal, where peasants organised to give landlords no more than one-third of their harvest—one part of teen bhaag. Hore was then a second-year student at the Government Art College in Kolkata. Tebhaga was a direct consequence of the famine. The demand to surrender a smaller portion of the harvest was to guard against starvation.

In May 1947, the CPI sent Hore to report on the workers’ movement in the tea gardens of north Bengal, historically the tea plantations are a site of extreme privation and hunger. In 1967, the Naxalbari movement would ignite in the Naxalbari area of north Bengal.

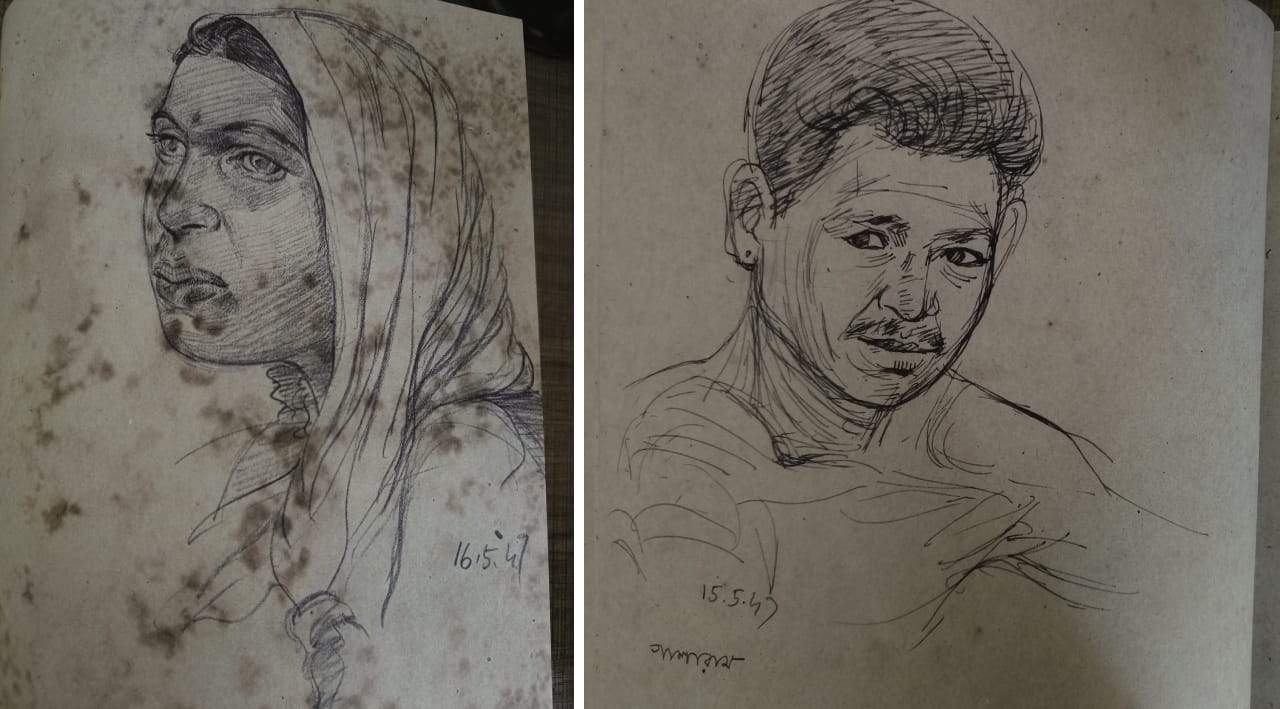

Somnath Hore’s famine sketches in Janayuddha, published in 1944. These images are sourced from The University of Heidelberg’s digitised volumes of Janayuddha, 1942-1944.

Somnath Hore’s famine sketches in Janayuddha, published in 1944. These images are sourced from The University of Heidelberg’s digitised volumes of Janayuddha, 1942-1944.

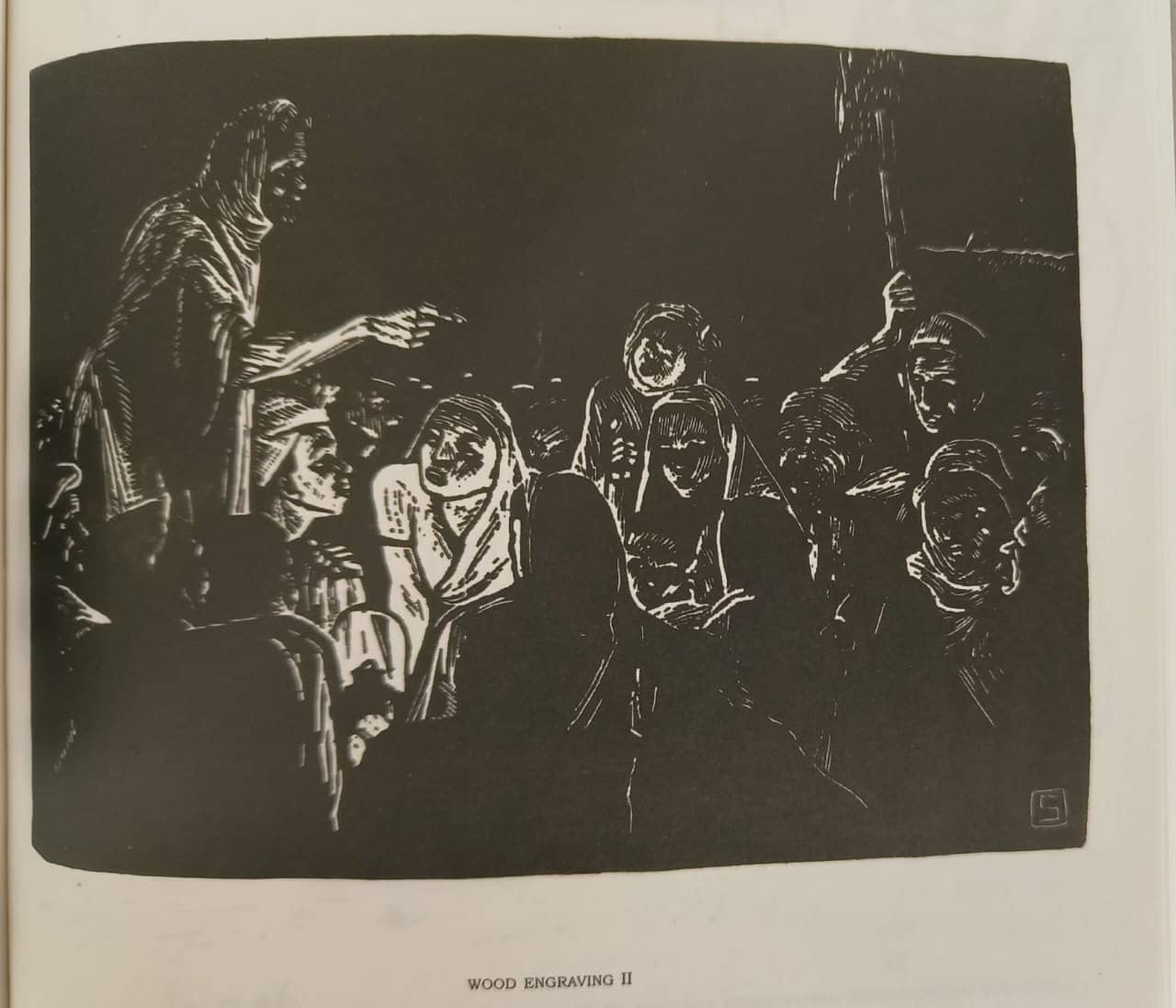

In The Tea Garden Journal in particular (images from The Tea Garden Journal published by Seagull Bools 2009), and in the handful of his sketches in Janayuddha, the imprint of Chittaprosad’s famine drawings is evident. Like him, Hore rendered many of the plantation labourers and famine subjects he encountered as portraits, offering direct or a degree of eye contact with viewers. The fourth image here is a woodcut from Tebhaga, published by Seagull Books, 2009. (Courtesy: Seagull Books)

In The Tea Garden Journal in particular (images from The Tea Garden Journal published by Seagull Bools 2009), and in the handful of his sketches in Janayuddha, the imprint of Chittaprosad’s famine drawings is evident. Like him, Hore rendered many of the plantation labourers and famine subjects he encountered as portraits, offering direct or a degree of eye contact with viewers. The fourth image here is a woodcut from Tebhaga, published by Seagull Books, 2009. (Courtesy: Seagull Books)

“Unknown to me the wounds of the famine of 1943, the barbarities of war, the horror of the communal riots of 1946 were impinging on my style and engraving themselves on it, till there came a time when whatever I did, whether it was chiselling a piece of wood, or burning metal with acid to create a gaping hole, or cutting and tearing with no premeditated design, it would throw up innumerable wounds, bodying forth a single theme—the figure of the deprives, the destitute, the abandoned converging on us from all directions,” Hore was quoted as saying in the book A Matter of Conscience: Artists Bear Witness to the Great Bengal Famine of 1943.

The Orphaned Weekly

It was unclear when People’s Age, the name of the weekly after the end of WWII, stopped publishing. But it is likely to be not long after PC Joshi was sacked from the party in 1947. Afterward, many artists like Chittaprosad and Somnath Hore withdrew from the party. Janah’s membership was cancelled with Joshi’s sacking. No one said it directly, but from my conversations at the CPIM and CPI’s libraries in Kolkata, it would seem that the internal bitterness in the party after 1947 meant that the paper was orphaned.

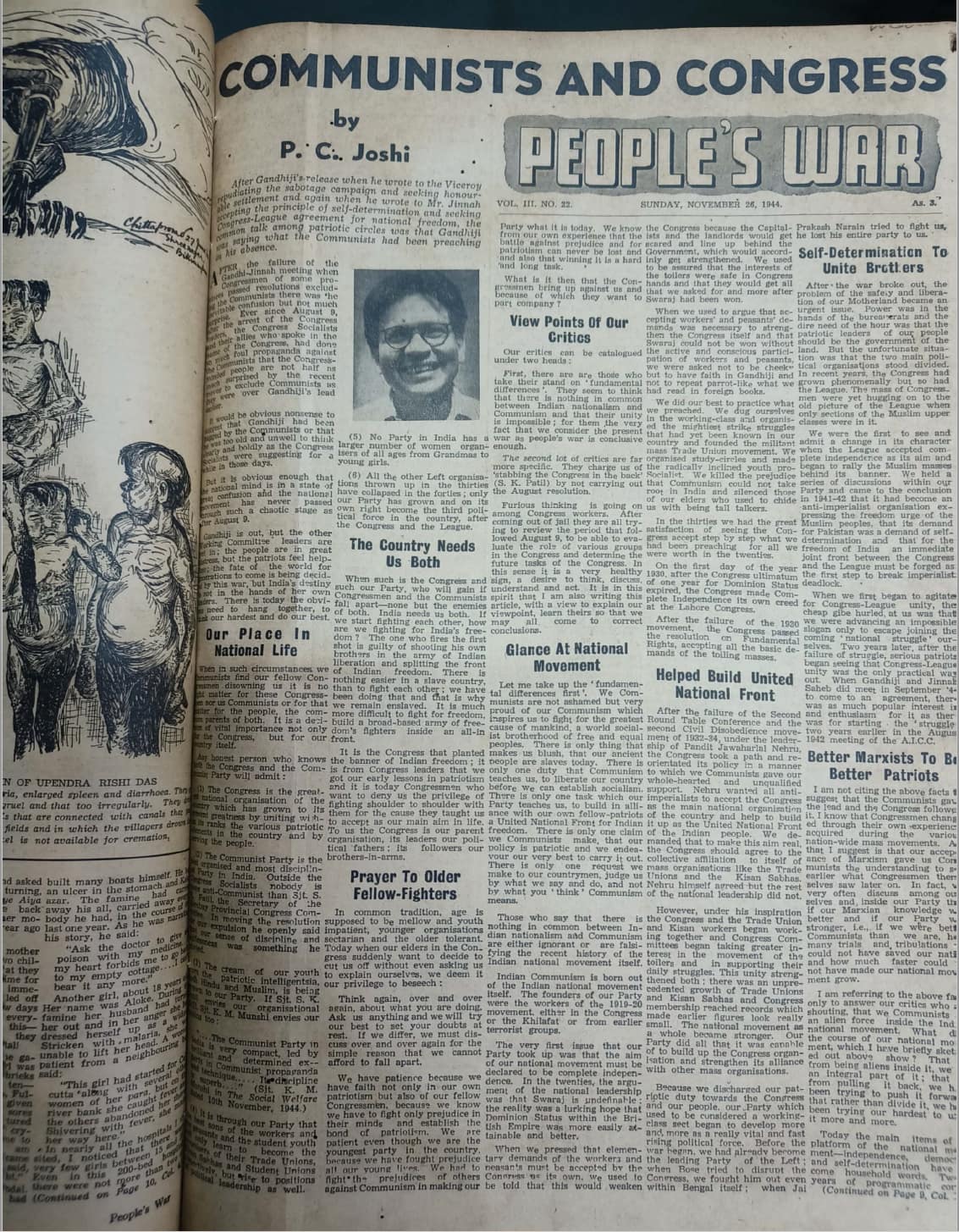

An op-ed by PC Joshi in the 26 November 1944 edition of the weekly. It has been said that Joshi’s closeness to Nehru and his party line of working with everyone is one reason for his sacking. Archival photo of the People's Age from the Ganashakti library, Kolkata, by Sohini

An op-ed by PC Joshi in the 26 November 1944 edition of the weekly. It has been said that Joshi’s closeness to Nehru and his party line of working with everyone is one reason for his sacking. Archival photo of the People's Age from the Ganashakti library, Kolkata, by Sohini

In 1951, Janah was readmitted to the party and tasked with bringing out a new weekly paper called the New Age. “I edited the Party organ, and very often wrote what I did not believe,” Joshi wrote about his stint as the editor of New Age. “I was denied the facilities to improve the paper to prove that I had lost my ‘old capacities’. These 9-10 years, the most mature years of my life, I literally wasted in sheer frustration breaking my head against the rock of ignorance and bureaucratism which in practice was political opportunism, plain factionalism and had become a chronic disease.”

“Although Joshi returned to the party in 1951, his position in the party was actually peripheral. With his diminishment, the writers, artists, singers, actors he had attracted to the party also started withdrawing,” said Prof Sobhanlal Dutta Gupta, former SN Banerjee chair at Calcutta University. “They saw that they no longer had a place in the new schema of the CPI. The party’s paper reflected this, it was all about the party’s line and internal organisational workings. That interest in culture and the world around was gone.”

A portrait of Kalpana Dutt, who participated in the Chittagong Armoury Raid of 1933, by Sunil Janah in Janayuddha. Joshi was married to Dutt. Deepika Padukone played Dutt in Ashutosh Gowariker’s Khelein Hum Jee Jaan Sey. Archival photo from the Janayuddha archives in the Ganashakti library, Kolkata, by Sohini.

A portrait of Kalpana Dutt, who participated in the Chittagong Armoury Raid of 1933, by Sunil Janah in Janayuddha. Joshi was married to Dutt. Deepika Padukone played Dutt in Ashutosh Gowariker’s Khelein Hum Jee Jaan Sey. Archival photo from the Janayuddha archives in the Ganashakti library, Kolkata, by Sohini.

Janah’s portraits of freedom fighter Mrs (Vijaylakshmi) Pandit (left) in the edition dated 7 January 1945 and Dandi march campaigner Sarojini Naidu (right) in the edition dated 14 January 1945. Archival photos from the People's Age in the Ganashakti library, Kolkata, by Sohini

Janah’s portraits of freedom fighter Mrs (Vijaylakshmi) Pandit (left) in the edition dated 7 January 1945 and Dandi march campaigner Sarojini Naidu (right) in the edition dated 14 January 1945. Archival photos from the People's Age in the Ganashakti library, Kolkata, by Sohini

AFTERWORD

The Communist Party of India (Marxist)’s library and the CPI’s library each held select, incomplete archives of the paper People’s Age. The National Library does not hold archives of the journal.

Chittaprosad withdrew from the CPI after Joshi was disqualified in 1947, although he maintained his Communist ideals throughout. He lived in a one-room apartment in Bombay and cooked his own meals, volume 1 of the Chittaprosad books by DAG recounts. He lived off whatever he earned from his art, sometimes this would cover only about ten days in a month.

Of the three artists who published in the CPI’s magazines People’s War and Janayuddha, Hore is the one who acquired a reputation in his lifetime. But like them, he too stopped being formally associated with the CPI.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!