“As the price of rice rose during the first half of 1943, the poor in the villages without sufficient stocks of grain in their possession found themselves unable to buy food,” the Famine Inquiry Commission wrote in the report published in 1945. “After an interval during which they attempted to live on their scanty reserves of food, or to obtain money to buy rice at steadily rising prices by selling their scanty possessions, they starved. The majority remained in their homes and of these many died. Others wandered away from their villages in search of food, and the mass migration of starving and sick destitute people was one of the most distressing features of the famine.”

Also read: 80 years since the Bengal Famine - Part 2: Portrait of the 1943 famine

We are 80 years from that early summer of 1943 when the price of rice rose and rose until...people starved. At least three million persons were killed in the 1943 famine, Amartya Sen writes in Poverty and Famines, basing his calculation on the figure provided by the colonial British government. Several anti-imperialist academics call it the “forgotten holocaust” or an unremembered genocide of the 20th century.

Also read: Book excerpt | Amartya Sen's 'Home in The World'

Perhaps, even within India, the story of 1943 has receded outside of Bengal - it is a footnote in public memory possibly because there is no memorial to those killed in the famine, not even a citizens’ initiative like the Partition museum in Amritsar. This could also be because most of what we know about the famine is through scholarly, complex work that was inaccessible to the public until the internet and book-sharing sites opened up academia to a degree.

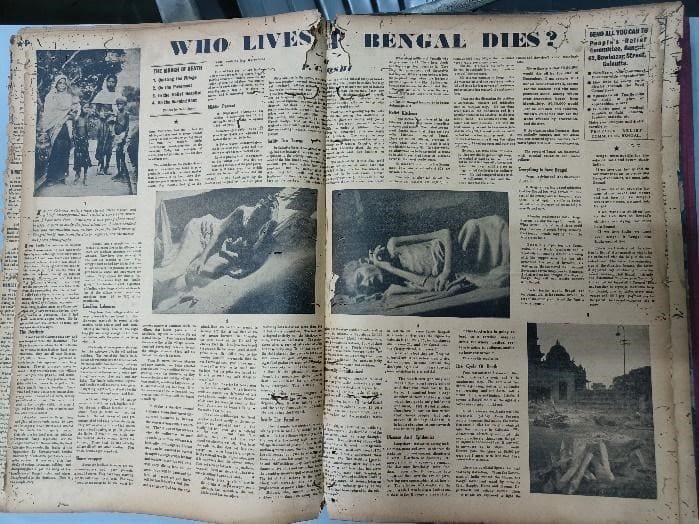

A two-page story by PC Joshi from November 1943, photos by Sunil Janah.

Yet, the famine of 1943-45 was in fact extensively and meticulously documented by a tabloid-sized weekly magazine called People’s Age, renamed People’s War during the years of World War II. It was published by the Communist Party of India and cost two annas, a price that was raised to three annas in September 1944. The weekly was edited mainly by Puran Chand Joshi (1907-80), the general secretary of the party from 1935-47, although he shared editorship duties with Dr Gangadhar Adhikari, who was another general secretary of the party.

But it was Joshi who would commission the late Sunil Janah (1918-2012), one of the greatest photographers to document India from the 1940s to the 1970s—the birth of the nation and her decades of youth. The famine would be his first major assignment. Joshi also commissioned Chittaprosad Bhattacharya (1915-78), now considered one of the most striking political artists in India. Joshi himself would report from across the large undivided Bengal province, and his articles were accompanied by Janah's photographs. Moved by the coverage of the famine, Somnath Hore (1921-2006), another major political artist, sent in his drawings of the famine affected and was published in the Bengali edition of People’s War, Janayyuddha.

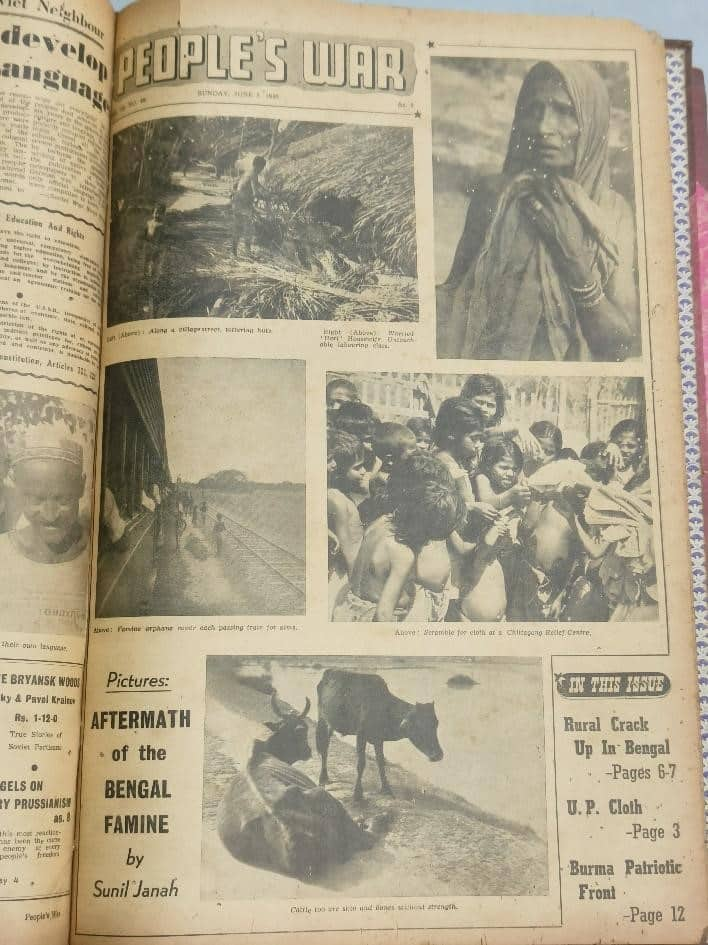

Lead page of the weekly edition dated 3 June 1945. Byline: Sunil Janah. Photo from the People's Age archive in the Ganashakti Library, Kolkata, by Sohini

Lead page of the weekly edition dated 3 June 1945. Byline: Sunil Janah. Photo from the People's Age archive in the Ganashakti Library, Kolkata, by Sohini

The Statesman in Calcutta has received credit for its famine coverage, and rightly so. Its editor at the time, Ian M. Stephen, was a British citizen but he was extremely critical of the colonial British government’s indifference to the distress in Bengal. On 22 August 1943, Stephen published a number of photographs of the starving lying listlessly or dead on the streets of Calcutta. This is believed to be the thing that embarrassed the British government to take action because the impact of the photographs travelled outside of Calcutta into the world.

Last page of The Statesman, Calcutta, edition dated 22 August 1943 that is believed to have first embarrassed the British colonial government. Note that the photographs carry no credit. Photo from the Statesman archive in The National Library, Kolkata, by Sohini

Last page of The Statesman, Calcutta, edition dated 22 August 1943 that is believed to have first embarrassed the British colonial government. Note that the photographs carry no credit. Photo from the Statesman archive in The National Library, Kolkata, by Sohini

But the famine did not affect Calcutta directly, except bringing streams of emaciated, stunned rural migrants into the city. The urban poor of Calcutta were covered by subsidized food schemes and did not starve. The Statesman’s coverage of 1943, however, remained Calcutta-centred in the subsequent months. By the second half of 1944, when Bengal reeled from the aftermath of the famine and the epidemics that came in its wake, The Statesman had ceased coverage of the famine. The only indication in the paper that the food situation was still precarious were the consistent ration notices for food, medicines, clothes issued by the then government of India.

A notice issued by the Department of Civil Supplies, Bengal, in The Statesman, Calcutta, edition dated 8 September 1944. It recommends that people eat "dalpuri", "ghugni" and "chhattu". Image from the Statesman archive at The National Library, Kolkata, by Sohini.

A notice issued by the Department of Civil Supplies, Bengal, in The Statesman, Calcutta, edition dated 8 September 1944. It recommends that people eat "dalpuri", "ghugni" and "chhattu". Image from the Statesman archive at The National Library, Kolkata, by Sohini.

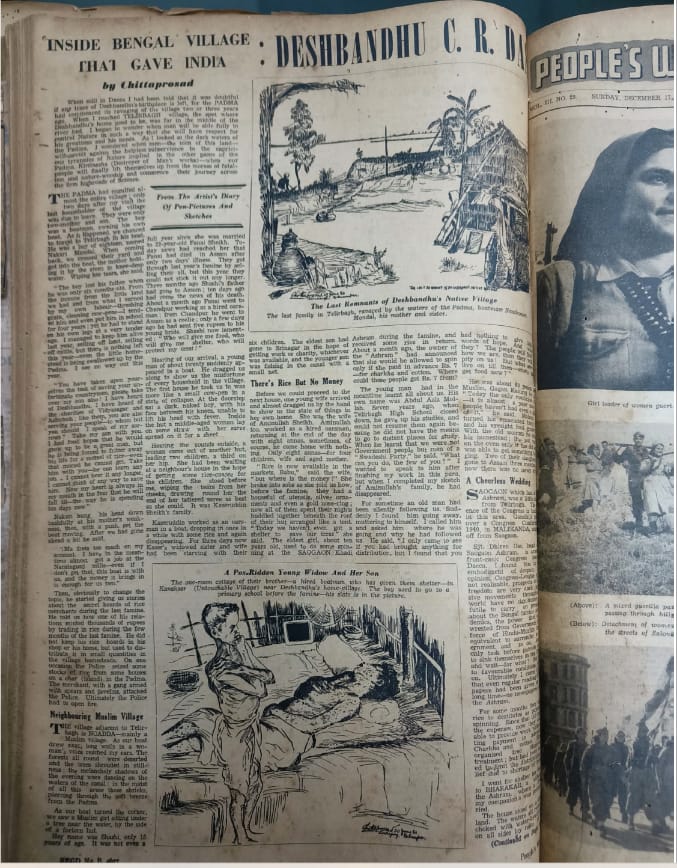

The effects of the famine continued well into 1945, People’s War found. Joshi had commissioned Chittaprosad and Janah to travel across the vast presidency to report on the situation, often travelling with them himself to write. Chittaprosad did this in an especially interesting manner: he identified districts and villages by the most famous resident of the area. Thus, Hooghly was Shyama Prosad Mookerjee’s home, Birsingha Vidyasagar’s village, Telirbhag village, near Dhaka, Chittaranjan Das’s place. Joshi also appeared to nurture their growth. It was not the norm for photographers in Indian newspapers to be credited for images. Janah was given full page photo spreads with a byline, Chittaprosad would often write the reports alongside his drawings.

Chittaprosad’s report from Chittaranjan Das’ village, in the edition dated 10 December 1944. Photo from the People's Age archives in the Ganashakti Library, Kolkata, by Sohini

Chittaprosad’s report from Chittaranjan Das’ village, in the edition dated 10 December 1944. Photo from the People's Age archives in the Ganashakti Library, Kolkata, by Sohini

The result is an outstanding archive of human-interest journalism—a unforgettable catalogue of a people wasting away without food, medicine, clothes. Their gaze tired and quiet, ashamed and sometimes beyond caring. It was also, particularly for the 1940s when news publications were text-dense, a pleasingly designed paper with handsome use of illustrations, photographs and cartoons.

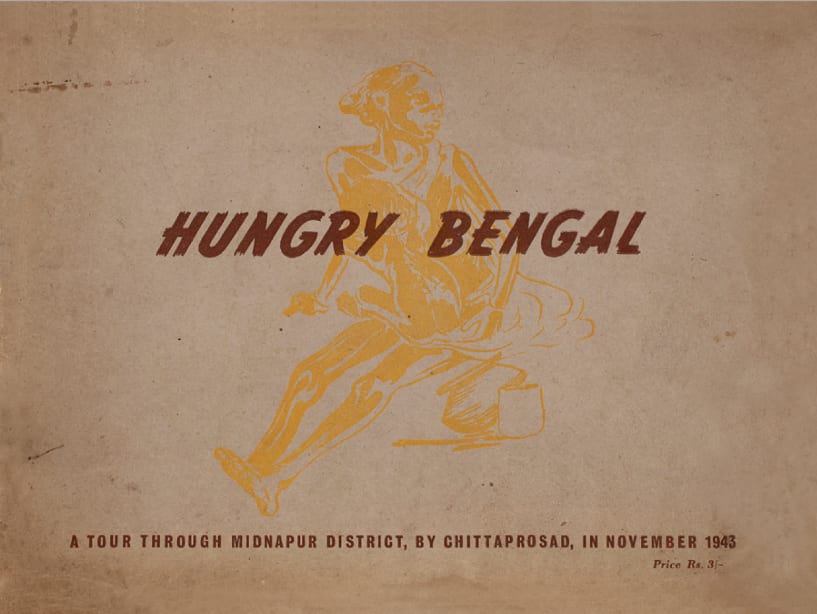

The reportage in People’s War forced the colonial government to react in uncharacteristic panic: the administration confiscated 5,000-odd copies of a slender book called Hungry Bengal that Chittaprosad published on his travels through Midnapore district undertaken for the People’s War. The paper also shaped a cultural output about the famine through the work of IPTA, or the Indian People’s Theatre Association, which composed songs and wrote plays, most prominently Nabanna by Bijon Bhattacharya, performing them across India. In 1946, there was the Hindi feature film Dharti ke Lal directed by IPTA member Khwaja Ahmad Abbas. Mrinal Sen, another IPTA member, would direct the Bengali features Baishey Srabon (1960) and Akaler Sandhaney (1980). These are three of the four films made on 1943 –the fourth being Satyajit Ray’s Ashani Sanket. Not least, the People’s Age also directly fashioned the conscience and art of three prominent Indians artists of the twentieth century—Chittaprosad, Sunil Janah and Somnath Hore.

The cover of Chittaprosad’s Hungry Bengal, confiscated by the colonial British government, courtesy Delhi Art Gallery

The cover of Chittaprosad’s Hungry Bengal, confiscated by the colonial British government, courtesy Delhi Art Gallery

Sunil Janah

Sunil Janah was a student in the then Presidency College and a member of the Leftist students’ union, when Joshi visited Bengal for a fact-finding tour on the famine. Joshi asked Janah to accompany him to take photographs and Janah, who waned to be a journalist and pursued photography as a hobby, went along. The famine of 1943 was his first assignment as a photo-journalist.

“People were starving and dying and I was holding a camera to their faces, intruding into their suffering and grief,” Sunil Janah said about his photography about the famine. “I envied people who were involved in relief work because they were at least doing something to relieve the people’s distress. It was a very harrowing experience, but I also felt that I had to take photographs. There had to be a record of what was happening, and I would do it with my photographs.”

Women queueing for rice in Lake Market, Kolkata, 1943. © Sunil Janah, courtesy Arjun Janah, suniljanah.org This photo is from the book Photographing India by Sunil Janah, Oxford University Press, 2013

Women queueing for rice in Lake Market, Kolkata, 1943. © Sunil Janah, courtesy Arjun Janah, suniljanah.org This photo is from the book Photographing India by Sunil Janah, Oxford University Press, 2013

This diffidence about intruding manifests beautifully in his photographs of the famine. His human subjects are almost never looking away in the photos, they were aware of his camera and looked back at it. Perhaps this was Janah’s way of securing a kind of consent for his “intrusion”. And this participatory gaze brings intimacy. As if the persons in the picture are right across you. Not a victim of a distant famine. But someone you know, looking quietly, tiredly at you.

After the famine assignment, Joshi asked Janah to join the Communist Party of India, the photographer and archivist Ram Rahman has written. He moved to the CPI’s office in Bombay where they lived in a commune. It was the party that bought him a Leica camera, Rahman writes, and on assignment for the party, he photographed Jawaharlal Nehru, Mohd Ali Jinnah, M.K. Gandhi, Sarojini Naidu, indeed all the leaders of the national movement. Janah would go on to produce an outstanding body of work on India from the 1940s to 1970s—her birth and formative decades—before leaving India.

Sunil Janah was thrown out of the party in 1947 when Joshi was disqualified. He returned to Calcutta where he set up a studio, founded the film society movement with Satyajit Ray, Chidananda Das Gupta and Hari Dasgupta. He received commissions to photograph many of independent India’s industrial and big dam projects. He would also photograph a number of tribes on assignment for The Anthropological Society of India, then headquartered in Calcutta. By the end of the 1970s, Janah would move to London and later the US. At the time, despite his body of work that spanned over four decades and took him all over India, he was not a well-known name. He has spoken about being hurt by the frequent uncredited use of his images.

The Communist Party of India (Marxist)’s library and the CPI’s library each held select, incomplete archives of the paper People’s Age. The National Library does not hold archives of the journal.

The second part of this story--on the artists Chittaprosad and Somnath Hore who carried the wounds of the famine lifelong, and PC Joshi and the end of the People’s Age magazine--shall be carried next Sunday.Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.