Could the world’s biggest polluter be on the brink of cleaning up its act?

That’s the promise of an announcement from China last week of a roadmap for cutting methane emissions — but the initial draft falls short. Often neglected in climate discussions in favor of carbon dioxide, the smallest hydrocarbon molecule, with the formula CH4, is also one of the most damaging. It accounts for about a quarter of the warming we’re experiencing.

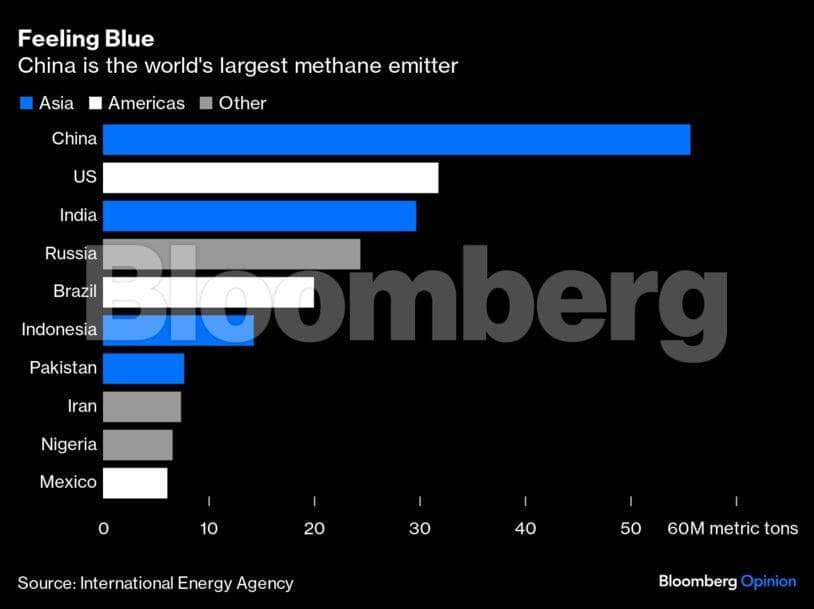

China is the largest CH4 emitter, and the most important holdout from the Global Methane Pledge, a pact agreed at the 2021 Glasgow climate summit. Quite apart from the damage from all that pollution, China hurts its own national security by throwing away a substance that could replace about a third of its gas imports.

Unfortunately, the plan announced last week doesn’t come close to fixing the problem. For one thing, there’s no overall target for how much current pollution should be cut, and by what date. We don’t even know what the starting line is.

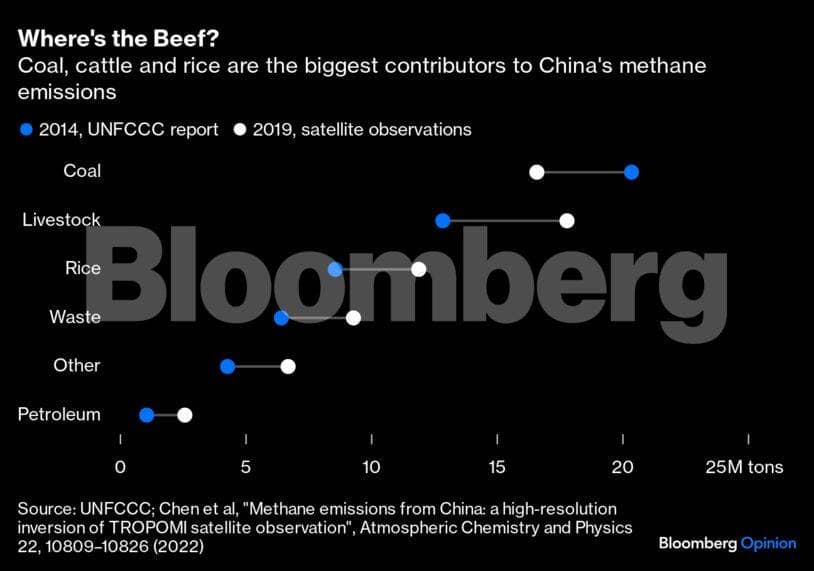

Though there are promises to improve reporting of how much methane the country actually emits (something that should be much easier these days, given how effective satellite sensing is in detecting CH4 leaks), the last time this was done officially was in 2014. That’s another era, given the pace of economic development since. For instance, coal mining, China’s biggest methane-emitting sector, was about four-fifths of its current size back then.

“It's a good starting point, and we have to start somewhere,” US climate envoy John Kerry told Bloomberg Television on Friday on the fringes of the Bloomberg New Economy Forum in Singapore. “Do we think there are some places they might be stronger? We hope so.”

Methane matters because it’s so potent. Over the next 100 years, each metric ton will cause about 28 times as much heating as a ton of carbon dioxide. The way the chemicals degrade in the atmosphere means its effect over the coming two decades is even worse, at more than 80 times the damage from CO2.

Cutting methane emissions also makes sound economic sense, in theory. Carbon dioxide is just waste material for most emitters, but methane is essentially identical to natural gas, a commodity the world is clamoring to secure. At least half of methane emissions from the petroleum sector could be eliminated at negative cost, meaning polluters are losing money by failing to clean up their act, according to the International Energy Agency.

China’s plan is not without concrete commitments. There are proposals that 80 percent of manure from farm animals and 60 percent of urban garbage will be reused by 2025, while 90 percent of urban sewage will be safely disposed of. That’s in the context of promises to utilize more of the waste methane that’s produced by all these materials as they decompose. Still, China could achieve each of those targets without capturing a gram of CH4 — the suggestion of attaching bio-gas digesters that could provide local heating and power is less an assurance, than a thought bubble.

Such operations could be profitable in theory. Waste bio-gas costs are typically below the $10 per million British thermal units that China pays for its methane imports and decline with scale, something the country’s huge cities are well-equipped to provide. The pledges, however, aren’t new: They’re reheated versions of targets that have been around for some time.

Facing pressure to come up with a proper proposal on methane ahead of the COP28 climate summit starting in Dubai later this month, this is the equivalent of Beijing producing those glossy, content-free corporate responsibility reports that big companies used to put out before shareholders started pressing them for better disclosure.

The biggest omission, however, is a clear plan for coal-mine methane. As we’ve argued, the emanations from China’s coal seams threaten not just the global climate, but also the country’s mining workforce and its energy security. They amount to nearly two-fifths of methane in the 2014 estimate, a proportion that may well have risen given the 18 percent increase in coal production since that date.

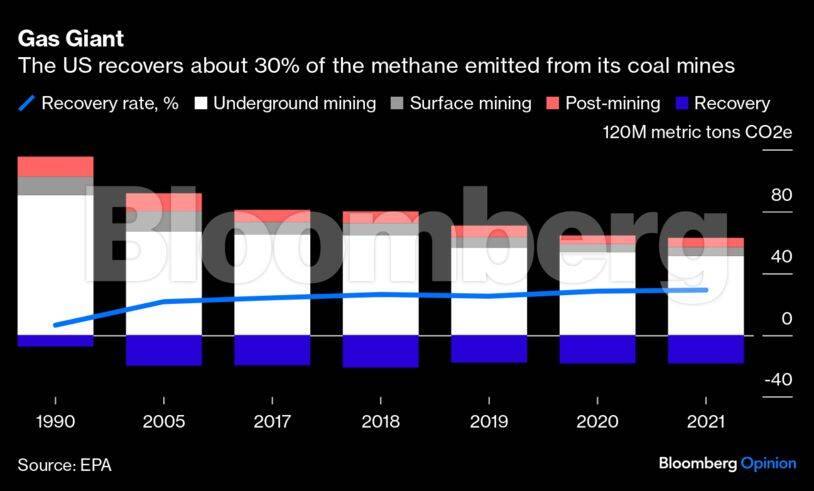

The promise here is to capture 6 billion cubic meters of coal-mine methane by 2030. That sounds like a lot, until you consider the scale of the problem. Total pollution from that source in 2014 was about 30 bcm, a figure that’s probably risen by now to at least 35 bcm as output has increased and moved into deeper, gassier seams. If China was recovering mine methane at the 30 percent rate that prevails in the US or the 50 percent the IEA believes is feasible, it could probably double or triple its capture target. Coal production in 2030 will hopefully be well below where it is now, but the commitment would still likely leave a mining sector whose methane emissions would exceed total greenhouse pollution from Germany. That’s not good enough.

Other routes of pollution reduction will be challenging. Cattle and rice account for a similar share of China’s methane emissions to coal, but techniques to reduce that depend on farm practices that still aren’t widespread and seem politically challenging to implement. A proposed “burp tax” on cows introduced in New Zealand may have contributed to the government’s defeat at last month’s election.

Judging by what is proposed, the best hope of reducing methane emissions at this point may simply be the rise of renewables and population decline translating into less coal being mined and fewer cows eaten. That’s not enough to put China anywhere near the path to net-zero.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. Views do not represent the stand of this publication.

Credit: Bloomberg

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.