The pandemic was a loud wake-up call for India’s school education system in general, and public education in particular. In the last one and a half years since the schools reopened, they are confronted with many challenges, including bringing out-of-school children back to schools, remedial teaching to cover for the huge learning loss, improving ICT( Information and Communication Technology) infrastructure in schools, training teachers on pedagogy including usage of ICT, improving quality of education, among others.

If all this wasn’t enough, states and union territories have plunged into the mammoth task of implementing the vision of the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020. Meanwhile, a considerable share of elementary schools still do not comply with all the provisions of the Right to Education (RTE) Act, 2009.

Catch all the LIVE updates on Budget 2023

Reality Of Higher BudgetingLooking at the immediate nature of most of these objectives, there was an urgent need for a considerable increase in school education budget for the upcoming financial year by the Union government, which needs to be complemented by the states in their forthcoming budgets. However, despite India’s public investment in education being far less than its own target for many decades now, this budget deprioritised school education yet again, except for announcing a handful of positive steps.

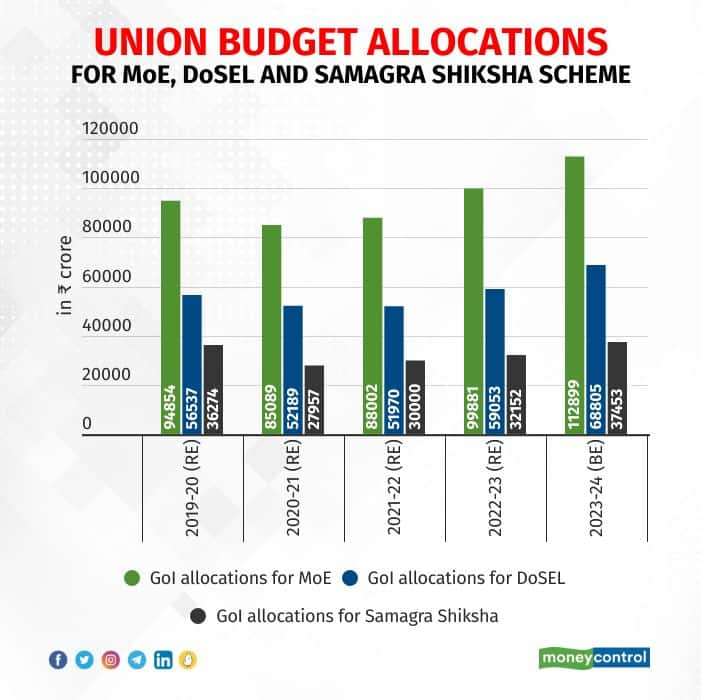

After funding cuts in the Department of School Education and Literacy (DoSEL) budget for two consecutive years during the peak COVID period, it saw a rise of 14 per cent in FY 2022-23. The latest Union Budget has allocated Rs 68,805 crore to DoSEL for the coming financial year (FY 2023-24), which is 17 per cent higher than the Revised Estimates (REs) of FY 2022-23. Similarly, there is a 13 per cent increase in budget for the Ministry of Education (MoE) as a whole.

However, we witness this growth rate because the budget for FY 2022-23 have been revised downwards in the current Union Budget due to relatively low releases and expenditure by GoI. Thus, we are basically comparing the budget estimates (BEs) for FY 2023-24 with relatively lower base figures than BEs announced last year. When compared with BEs for FY 2022-23, the increase appears to be only 8 per cent for both DoSEL and MoE.

Of the DoSEL budget, funds are directly transferred to states through the Centrally Sponsored Schemes (CSS), which provide a window for states to prioritise aspects such as the quality of education, and implementation of national goals, as the majority of states’ (non-CSS) funds get spent on committed liabilities such as salaries. Samagra Shiksha is the largest CSS on school education in India and is the primary financial vehicle to implement key provisions of the Right to Education (RTE) Act, and the National Education Policy (NEP), 2020.

In spite of the crucial role, it received one of the lowest budget allocations during the peak COVID-period of FY 2020-21 at Rs 27,957 crore. Since then, even though there has been a rise, the pace has been quite slow. As revealed by this Budget, the REs for the current financial year (FY 2022-23) have been 14 per cent less than the BEs. The GoI allocation for the coming financial year at Rs 37,453 crore, is actually disappointing. While it is 16 per cent higher than FY 2022-23 REs, it is similar to the BEs for FY 2022-23.

Why Generous Allocations?The Finance Minister spoke about re-envisioning teachers’ training by developing the District Institutes of Education and Training (DIETs) as “vibrant institutes of excellence”. DIETs are primarily funded through Samagra Shiksha and therefore, there should have been all the more reason for higher budgets. On a separate note, a positive announcement is the move to recruit more than 38,000 teachers and support staff for 740 Eklavya Model Residential Schools for Scheduled Tribe (STs) in the next three years, which is implemented by Ministry of Tribal Affairs and not by DoSEL.

NEP’s vision of universalisation of school education by 2023 means that every child should be able to access pre-primary, elementary and secondary education. Considering that net enrolment ratios at secondary and higher secondary levels are still very low, greater public investment is necessary to ensure access to secondary education, by addressing some of the challenges in terms of provisioning of schools and affordability.

Moreover, India has witnessed a rise in government school enrolment for two consecutive years- 2020-21 and 2021-22, with a parallel decline in private school enrolment. This again calls for higher budget allocations for public schools to ensure child-specific services to all children. An 8 per cent increase in DoSEL budget for FY 2023-24 is equivalent to a 3 per cent rise in real terms. While this is still an increase, technically, India’s public education requires budgets that are far higher.

Mridusmita Bordoloi is an Associate Fellow with the Accountability Initiative team at the Centre for Policy Research (CPR), Delhi. Views are personal and do not represent the stand of this publication.Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.