Manisha Mohite, a 38-year-old street-food seller in Mumbai’s Goregaon, is struggling to feed her family of seven.

Mohite may have to shut her five-month-old chaat stall in Goregaon, a slum area, because of the increasing prices of food articles, oil and cooking gas. Even to pay for daily necessities has become a struggle.

“Almost everything is costly, right from onions and tomatoes to oil. Where do we get money,” Mohite said in between serving a customer.

The number of customers visiting her stall has fallen sharply as inflation surged, she said.

“No one wants to pay even Rs 5 more on a chaat plate. We may have to close this soon,” said Mohite.

Consumer price inflation in April accelerated to 7.79 percent, the fastest pace since the 8.3 percent recorded in May 2014, indicating a sharp uptrend in prices across the board and remaining above the upper limit of the central bank’s tolerance band of 6 percent for the fourth month in a row.

Expectedly, it is the poor like the Mohites who have been the hardest hit. If Mohite is forced to shut her chaat stall, her family – three children, elderly parents and an ailing husband – would find themselves in an economic abyss. Her husband Ritesh used to work at a local restaurant and lost his job during the COVID-19 lockdown.

Across the board

For the poor, the scourge of inflation followed job and income losses during the pandemic. The cost of food, housing, transport and healthcare have all risen by 50 percent since the middle of last year, data suggests.

High fuel prices have pushed up the prices of most commodities and services. Global oil prices have risen above $100 per barrel because of geopolitical tensions that climaxed in Russia’s February 24 invasion of neighbouring Ukraine, leading to shortages in many commodities.

“The cost of LPG (liquefied petroleum gas) has shot up; we are unable to save anything by the end of the month,” said K. Rajan, a 42-year old who sells tender coconuts for a living in Mumbai’s Andheri.

“A few months back, I was able to save somewhere between Rs 3,000 and Rs 5,000 per month. Now, this has dropped below Rs 1,000. Will I save this for my son’s education or spend it on a vacation?”

The price of a non-subsidised 14.2 kg domestic LPG cylinder increased to Rs 999.50 in Delhi this month, up from Rs 949.50 previously.

Double whammy

Borrowing costs have gone up too with the Reserve Bank of India raising its benchmark repo rate by 40 basis points on May 4 to 4.4 percent. One basis point is one-hundredth of a percentage point. More rate increases are expected.

Any increase in the price of essential commodities will force people to cut back on their priorities, say economists, who are doubtful whether monetary policy tools would be able to contain supply-driven inflation.

Inflation hit India’s poor and the middle class when they were yet to recover from job losses and pay cuts that resulted from the pandemic. According to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), at least 7 million Indians lost their jobs because of COVID-19.

Inflation has forced families to modify their monthly budgets and alter spending habits. When prices of necessities like food, oil and transport increase, most consumers opt to pare discretionary spending like that on recreation and entertainment.

At least five consumers from lower income groups Moneycontrol spoke to said they have had to pare discretionary spending drastically because they did not have enough income left after paying for necessities.

“We have started buying cheaper items like oil and soaps to make sure we stick to our monthly budget,” said Naresh Verma, 32, who works in the hospitality sector.

“We have cut down ordering food from restaurants and occasional movie outings have also stopped,” Verma added.

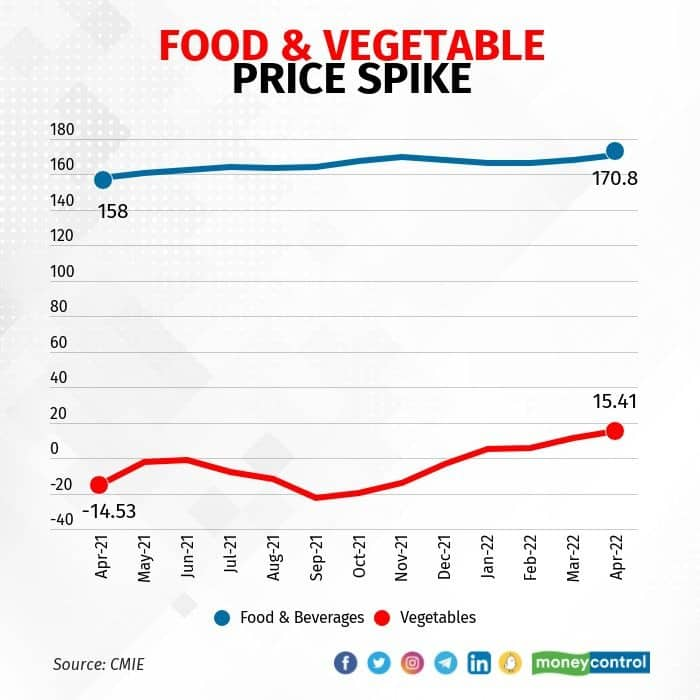

In the last one year, prices of food and beverages have risen by 8.4 percent. While vegetable prices had contracted 14.53 percent in April last year, it jumped 15.41 percent last month, according to government data.

Erosion of purchasing power

“Consumer demand was already fragile before the escalation of price pressures,” said Upasna Bhardwaj, senior economist at Kotak Mahindra Bank. “The recent worsening of inflation has further eroded the purchasing power of the consumer. The price pressures are seen across the board, thereby limiting spends on discretionary items.”

The hospitality and entertainment industry were the worst-hit by the COVID-19 lockdowns and have just about re-started their businesses. According to a Mumbai-based restaurant owner, the reduction in discretionary spending has influenced food ordering patterns.

“It is quite evident that people have cut down spending on food compared to what it was a few months ago. The impact is already visible in my business,” said the restaurant owner.

Small businesses like his have partly passed on a part of the increase in the prices of vegetables, meat and poultry to customers, but that has in turn hurt consumption.

“Footfalls have been lower month-on-month right from February. We either have to take the price hit and/or offer hefty discounts or cashbacks to consumers,” said the person cited above.

A challenge for RBI

The unusual acceleration of inflation in April was primarily triggered by costlier food items. That was the fourth straight month inflation remaining above the upper band of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI)’s comfort zone.

The RBI’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) has the mandate of keeping inflation in a 2-6 percent band. Failure to meet this target for three consecutive quarters will mean the central bank will have to explain to Parliament why in writing.

That possibility is likely to arise by September, wrote former RBI Governor D Subbarao in Moneycontrol on May 10.

According to Soumyakanti Ghosh, group chief economic adviser of State Bank of India, the rise in prices of food and beverages contributed 58 percent to the rise in April’s headline print over February, mainly due to the Russia-Ukraine war and its spill-over impact on fuel prices.

Here comes ‘shrinkflation’

High prices also lead to what some economists call ‘shrinkflation’ or the practice of companies reducing the size or quantity of a product while keeping the price constant.

“Are we seeing a phenomenon of shrinkflation? Yes looks like it. Most FMCG firms are downgrading across the board or reducing the weight of fixed-price items to cope with higher input costs/or to cut costs,” said Swati Arora, economist at HDFC Bank.

This is already evident in the market where some FMCG companies – FMCG is the acronoym for Fast-Moving Consumer Goods -- have started reducing the size of products across the board or cutting the weight of fixed-price items to cope with higher input costs.

“For example, a bar of dishwashing soap of a prominent company now weighs between 135 and 140 grams, compared with 155 grams about a few months ago for the same Rs 10 price,” said a Mumbai-based distributor.

In turn, this leads to higher frequency of purchases by consumers, hitting their disposable incomes, said economists.

“It is difficult to assess the impact of shrinkflation due to lack of data,” said Gaura Sen Gupta, India Economist at IDFC FIRST Bank.

“At first glance it could help companies limit the impact on revenues by giving customers the option to buy small quantities," Sen Gupta said.

(This is the second part in a Moneycontrol series assessing the impact of high retail inflation on the Indian economy. You can read the first part here)

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.