If walls could speak what stories it would tell of the people who live confined within them. The walls of the house, in Sad Letters of an Imaginary Woman, exquisitely shot by lensman Ashok Meena, are as blue as the lives of the women who inhabit it. The film produced by Sri Lankan filmmaker Vimukthi Jayasundara and India’s Nila Madhab Panda and Ajender singh, premiered at the 2024 Busan International Film Festival (BIFF) in South Korea. Its Jaipur-based director Nidhi Saxena is the first Indian woman to have won BIFF's supporting programme Asian Film Fund 2024 for post-production.

Nidhi Saxena, in her debut feature film, has made a lyrical cinema about a middle-aged Nidhi (Anamika Tiwari) who lives in a decrepit old house with her ageing mother Meera (Bhadra Basu). Being together in their silences and emotions, in their loneliness and depression, of submerged irascibility and buried hope, of unclosed chapters, trapped with memories of an inexpungible past, with a generational gendered trauma.

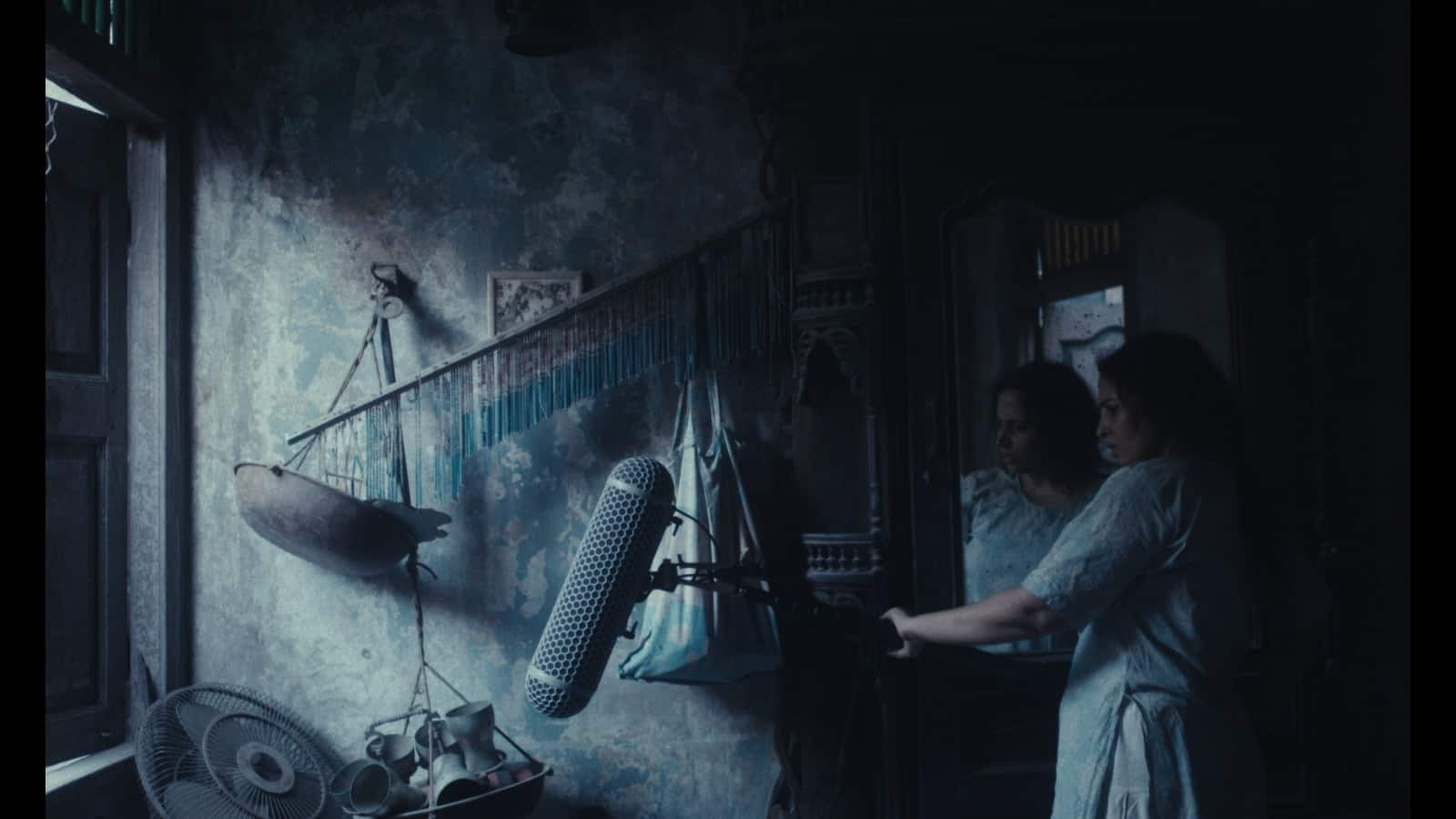

If an older Meera sits watching a flickering TV screen, in what seems like a disaster-ravaged room, an apple in her hand falls and rolls down the floor, older Nidhi wants to sleep, in a fetal position, hoping to never wake up, but looks down the bed to play with a toy train. Older Nidhi carries a boom mic, hearing the walls, amplifying the sounds muted within the four walls and the sounds outside of things (travel: planes, trains) inaccessible to them. She telephones her younger self — recall Karthik Calling Karthik? But this is more a case of schizophrenia than Dissociative Identity Disorder. Acutely aware of the loneliness of her childhood, older Nidhi wants to be there for younger Nidhi. Despair has become second skin to Meera, who could have had a different life if she could have escaped her dead marriage. If Nidhi's father remained absent mostly (when he comes, flowers bloom but also glasses tumble down the stairs), her mother had been an absent presence. The exhaustion of caregiving has eaten up the lives of both Meera and Nidhi. It has become akin to a disease for both. The two women, facing their entwined destiny, are indistinguishable. Both living, breathing, crushed beneath the weight of an unbearable heaviness of living. Both, dead inside. Both, growing on each other, like fungus. This house — blue, bare, barren — is not a "room of their own", not a world of their own choosing. They cohabit the space like two spectres, they are not friends — maybe because of Nidhi, Meera could never leave outwardly, but, inwardly, Meera long left the world Nidhi grew up absorbing — conjoined by a sense of lack and melancholia.

Anamika Tiwari in a still from 'Sad Letters of an Imaginary Woman'.

Anamika Tiwari in a still from 'Sad Letters of an Imaginary Woman'.Saxena, through these two women characters, has spoken for millions of women in patriarchal societies like ours, especially in those homes where women, their lives and desires, are confined within the four walls of a house. Through Nidhi and Meera, Saxena contextualises a universal theme through the local, a subject that is almost never a dinner-table conversation. As many north Indian homes will observe Karwa Chauth tomorrow, where women, tradition-bound, annually, fast for the well-being of their husbands, it augurs the question: who thinks about the women’s well-being, mental and emotional? Is it enough to keep deceiving ourselves by telling ourselves that we are happy so long as our husbands and children are well-cared-for, well-fed and happy?

Saxena is also a published Hindi author, in whose work tiles, sadness and birds recur (Chidiya Ud, a fiction; Bulbul-e-Paristan on Fatima Begum, India’s first female director; and Ek Udaas Swed on Swedish filmmaker Ingmar Bergman). In her film, the alumna of the Rajasthan School of Art and Pune's Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) shows that the house these women call home is a trap, a social cage, but even in their despair, Saxena has made the caged birds sing. To use Vimukthi's words, Saxena has eschewed the narrative, the linear format and attempts at storytelling that cinema is majorly reduced to and has created "pure cinema", belonging to the avant-garde Cinéma Pur tradition started by the French, that returns cinema to its essence of the visual and movement, of rhythm and emotion/sensation.

Here’s an exclusive interview with her from Europe, where she’s working on her second film, The Secrets of the Mountain Serpent. Excerpts:

A still from 'Sad Letters of an Imaginary Woman'.You’re the first Indian woman to get the Busan International Film Festival’s Asian Film Fund 2024 for post-production.

A still from 'Sad Letters of an Imaginary Woman'.You’re the first Indian woman to get the Busan International Film Festival’s Asian Film Fund 2024 for post-production.Yes. But this isn’t a reason to celebrate. So many films are made in India, but there will be about three-four per cent women directors from that pool, and in that indie films…it’s like as if the world is rejoicing that you are the first girl from your village to go to school…but why, why was the social structure before not such that women could have accessed education? You know, I sold my Maruti Swift car to make this movie. I had little money to make this indie film when I started, around Rs 3 lakh. Whoever I approached told me that a film can’t be made with so little money. But I was adamant that I will make this film.

How much of the film is autobiographical?I will not say that this is autobiographical, but I’ll say it’s more a personal film, because I think loneliness is a personal feeling. Loneliness, anxiety and depression are personal. This is what I have seen around me. Women going through a certain kind of loneliness. They are trapped in a house. I grew up in a very middle-class family in Jaipur. I saw my aunts and my sisters confined in one house for their whole lives. Not that they were not allowed to go out, but socially it was framed such that women would stay at home mostly, and then she is appreciated more. I’m a little hesitant to say that it [this film] is autofiction. The feelings are autofiction.

(Smiles) That I did very smartly to confuse people. I wanted the audience to think that it’s my story.

A still from 'Sad Letters of an Imaginary Woman'.Mothers and daughters usually have difficult relationships, neither our society nor our films talk about it.

A still from 'Sad Letters of an Imaginary Woman'.Mothers and daughters usually have difficult relationships, neither our society nor our films talk about it.Our films don’t talk about women at all. So, my film is 78 minutes’ film, in which the screen time of a man is for five to six minutes. A lot of male actors I approached for the father’s role said to me that they hardly have any role (screen time) in the film, that the film doesn’t belong to them. And I would look at them to see how entitled male actors are. It has been centuries that our films have given so little screen time to women, and even in those few moments, what are they shown as doing. Men never had any issue with that. But I’m very happy for this fact that my film is 78-minute long and the male character comes for only four to five minutes. And we see women back to back.

What acts of rebellion by the women in your personal life did you see growing up?I think when women fall in love outside of marriage, it’s an act of rebellion, because then she’s somehow trying to reclaim her body. In this society [patriarchal], when a woman gets married to someone, she becomes someone’s property in a sense. So, when she falls in love, she reclaims her individuality, her right to fall in love. And what I did was I never got married, twice I was about to get married and I called it off. My parents are progressive, but still they are very traditional. So, they always wanted me to get married at the age of 24-25. All of my friends were getting married, but I didn’t. I think this is a very rebellious act for a woman in her mid-30s. And, I made this film. I think this is one of the most courageous things I did.

Even my [Sri Lankan] producer Vimukthi Jayasundara was telling me that for my first film, this kind of film is very risky. It can be our third or fourth film, but not the first. But Ajender (Singh), one of my Indian producer, chose this screenplay and he said, I should make this film. This is so me and this is so experimental.

Tell us about your idea of method acting. You and your mother stayed isolated in a haveli before the making of this film?So, it was not a haveli actually. It was a very old house, around 300-year-old house. It was an abandoned house in Ahmedabad. I had a very rough idea of the screenplay. Actually, the final screenplay that you see, some parts of it, I had written almost 10 years ago. And then I was doing one workshop with Kamal Swaroop (teacher at FTII) on the politics of families and RD Laing [Scottish psychiatrist who wrote extensively on mental illness, especially psychosis and schizophrenia]. And we were watching [John] Cassavetes, [American] filmmaker’s film A Woman Under the Influence (1974). During that workshop, I completed the sketch of this old, small screenplay into a feature film. I started to look for the locations. I stayed there, sometimes totally alone. And completed this screenplay over there. I think that house inspired me a lot. Locations inspire me a lot. I first choose a location and then start to put characters in that.

Did your mother go through some sort of emotional swings while she was doing this for you?I didn’t ask this to her, but my mother was a clerk in the State Bank of India, now she’s retired. If she was not a working woman, I couldn’t have done anything in life. I could have been an engineer, teacher, doctor or an anchor. My father and my brother, though they are supportive, but they never understood this thing of mine, of making art, I was painting and sculpting. My father is a good person, but he was not with me when I was making paintings, sculpting, or filming. My mother was behind it all. She used to buy me colours. And so, yes, she did this for me. She was my driver as well as my line producer. One of my actors, Bhadra Basu, who plays the old mother in the film, she is from Calcutta. She told me, Nidhi, I don’t want to sleep alone. Is it okay if you share the room with me? So, I said, I sleep with my mom. So, the three of us were sleeping in the same room. And she [Basu] used to make fun of me on the sets that she [Nidhi] sleeps with her mom, and puts her leg on her mom while sleeping. So, I couldn’t have done anything, I couldn’t have done painting or made this film if my mother was not around.

Bhadra Basu in a still from 'Sad Letters of an Imaginary Woman'.Your film doesn’t have a linear narrative plot, it’s quite unfilmable, a feature-length idea. How did you go about making your crew, your actors and cinematographer, see your vision?

Bhadra Basu in a still from 'Sad Letters of an Imaginary Woman'.Your film doesn’t have a linear narrative plot, it’s quite unfilmable, a feature-length idea. How did you go about making your crew, your actors and cinematographer, see your vision?What I felt that nobody liked the screenplay because they didn’t understand what was going on, but because my crew comprised my friends, they did it somehow. But I changed almost three cinematographers. One cinematographer told me three days prior to the shoot that he couldn’t understand. I started with a very indie film. Since I stayed in that location for so long, I knew the nerve of that house. We did the blocking, etc. Another cinematographer friend involved with my second film said that I don’t write a complete screenplay, I wanted to tell him that I don’t want to. I want to let it evolve, organically. So, half the things are in my head, a skeleton is on paper, and I knew what emotions were important.

I was very functional. So, I am a huge fan of [Soviet filmmaker Andrei] Tarkovsky, and I read how he used to work with actors. He always used actors as models, his emphasis [to them] was: don’t do anything. Just be there. So, I was very clear. I gave them [the actors] a certain emotion [in a scene] and told them to be in that emotion, to just be there. We sometimes cater the film as individual scenes. Like one scene is one film, it’s not connected to anything else.

(Smiles) But, yeah, I think when I was shooting, my actors and my technicians were not taking me seriously. They were just following what I am saying. That’s how we could make this film. I don’t give any freedom to anyone. In fact, once, I was a bit cruel. One of my actors cried in a scene, and she would have gone through catharsis to tear up at that moment, but I told her I don’t want tears in this shot.

Some of the images and frames reminded me of Tarkovsky’s films. Especially the scene where the mother brings in the candle, shielding the flame against the gush of wind, prompts the candle scene from his Nostalghia (1983). How much of a visual influence was his works on you when making Sad Letters of an Imaginary Woman and who were the other filmmakers who have inspired you?I love [Thai filmmaker] Apichatpong [Weerasethakul] and [Malaysian filmmaker] Tsai Ming-liang’s work. And I have loved Tarkovsky for so many years now. In the sense of production design, in keeping it realistic, I took references from Apichatpong. He is marvelous. I tried to show his films to my crew, especially Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010), in which even the ghost joining the dining table feels so real, like an everyday thing.

[Tarkovsky’s] Nostalghia scene was a conscious choice, because when I wrote the scene of the mother bringing in the candle, I was thinking how to design this scene. How is the mother going to walk? We have seen so many similar scenes on screen before, [Turkish director] Nuri Bilge Ceylan has shown this bringing-the-candle shot in his films. I was thinking how to and then this great scene came to me, of this man crossing the pond carrying a lit candle which shouldn’t be blown out, and I went back to Nostalghia, which is so philosophical.

The scene design was such that…because everyone follows the rule of close-ups and mid-shots, in this film especially, the house was the protagonist for me, was a character for me, and a very important character because I wanted to give this feeling of that boredom when someone is trapped in one abandoned house for so long. And I always believe, which I said in the film also, that if those walls could have said something about people, they will reveal different information for everyone than what is known. Like I’m something else in my social life and inside my house I may be a very different person. Locations are always very important for me, more important than the characters.

How did you go about your cast, the mother and daughter.Finding the daughter (Anamika Tiwari), who’s in mid-30s to early 40s was not hard but finding the mother was very tricky, very hard to find a working actor in her early 70s. Bhadra Basu brought in that intense look, it was marvelous. The shooting was tough, there’s no sleep schedule when you are shooting. Some of Bhadra’s scenes were shot at 2 am and 4 am. I wanted an intense look for the character, not a strong one. And I just wanted this actor to just be there and see.

A still from 'Sad Letters of an Imaginary Woman'.Each frame is like a painting, some remind of actual paintings. Here is a Frida Kalho’s The Two Fridas (1939) with the older Nidhi and younger Nidhi, there is Pablo Picasso’s Girl before a Mirror (1932), as the older Nidhi sits, in stark bareness, in front the mirror, her image broken into three selves of her. Did you want to infuse painting conceptually into filmmaking, given there are no dialogues or narrative storytelling in your film?

A still from 'Sad Letters of an Imaginary Woman'.Each frame is like a painting, some remind of actual paintings. Here is a Frida Kalho’s The Two Fridas (1939) with the older Nidhi and younger Nidhi, there is Pablo Picasso’s Girl before a Mirror (1932), as the older Nidhi sits, in stark bareness, in front the mirror, her image broken into three selves of her. Did you want to infuse painting conceptually into filmmaking, given there are no dialogues or narrative storytelling in your film?I strongly believe that cinema is not closer to literature, cinema is closer to music, architecture and painting because it needs some rhythm. If I don’t give you a rhythm, then you won’t be able to sit in front of a screen for 3 hours. Painting has a frame, films have a frame. Music has rhythm, film has a rhythm and when we are playing with time and space, then we are already playing with architecture and music. It’s okay to tell stories through cinema, but cinema is not the medium of telling stories at all. If you are doing this with cinema, then you are reducing it, you are losing its potential.

I took influence and references from all these paintings. Especially this Picasso’s painting, Girl before a Mirror, it has been used, internationally, some thousands of times in films, and used very differently.

Sound is very important to the film. It is almost like a parallel aural film within this film. You have not used music to heighten the emotions, but to capture the ambient noise. Sound is being deployed almost as a metaphor and of aspirations. There are sounds of aeroplanes and trains, but you don’t see them. The boom mic amplifies the sounds in the room, as if the walls are speaking.So, we built a narrative which is not there in the film. We were very conscious that when we were doing the sound, it had to be a different narrative. It should be the sounds and noise that take place in people’s minds. My approach was to have those sounds of things that are not visible in the film. The sound should tell a different story. It is a second narrative, the story of the mother, of her inner life. Maybe the mother has a lover and maybe he works on a ship, so portray that through sound.

What do the walls speak? If you go to a very old place, it will have its own energy and you’ll be able to feel it. So, I wanted to show, that this old house, what all it may have witnessed and absorbed, what would its energy be like?

I found inspiration in [Mexican writer] Juan Rulfo’s work, even though he’s a novelist, but the way he writes about sound, for instance, some character of his was locked in a room hundreds of years ago, and the sound of that person’s shrieks are being heard now. So, yeah, I took my sound referrences from Juan Rulfo’s Pedro Páramo (1955) a lot.

Your next film is also on women?Oh, yes. We have already started to work on that film. It’s fabulous. It is about women and women’s desires. It’s a very fiery film. It’s called The Secrets of the Mountain Serpent. I’m in Europe to work on that film.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.