There is a certain way of doing e-commerce we have got used to. Everyone has a different app they prefer for different needs like ordering fast fashion, fast food or hailing a cab.

Often, though, there are shortcomings. Your go-to food app may not have that new pizza place listed on it. Or the app that you like to use for electronics purchases may not have the cool new smartphone model. But you might insist that all eateries of your choice are there on one food app and all electronics or clothes you want to buy on another e-commerce app.

But one thing is undeniable—there is no way that you can find all the cool mobile phones from a food app or order food from a fashion app. In effect, there is no e-commerce platform that can really claim to be ‘the everything store.’

If one attempted to think of this problem from first principles, there would be two solutions to it. First, add more and more types of goods and services to one platform to make it a super-app. This is something that has been done by platforms like WeChat in China and GoTo in Indonesia. Some e-commerce platforms in the US and India have also taken a shot at becoming a super-app but with little or no success.

Experts also have raised questions about the threat to competition when a few e-commerce apps become too big or powerful. In theory at least, such platforms can unilaterally dictate pricing for consumers or commissions from sellers.

The second way to solve the everything store problem is breaking the silos that separate different e-commerce platforms—a concept that is known as interoperability in the software world.

What this means is to make the food app, the fashion app, the payments app, the ride hailing app—or any other e-commerce aggregator for that matter—talk to each other so that the consumer can place an order for anything from any app.

And this exactly is what the Open Network for Digital Commerce (ONDC) aims to achieve.

Built on the guardrails of software designed by the Beckn Foundation, a non-profit backed by Infosys chairman Nandan Nilekani, ONDC wants to replicate the success of the United Payments Interface (UPI) in digital payments for digital commerce in India.

ONDC’s thesis is simple: build a digital standard for the e-commerce industry that allows any seller to connect with any buyer on the network.

But that is easier said than done.

Many pieces of the puzzle

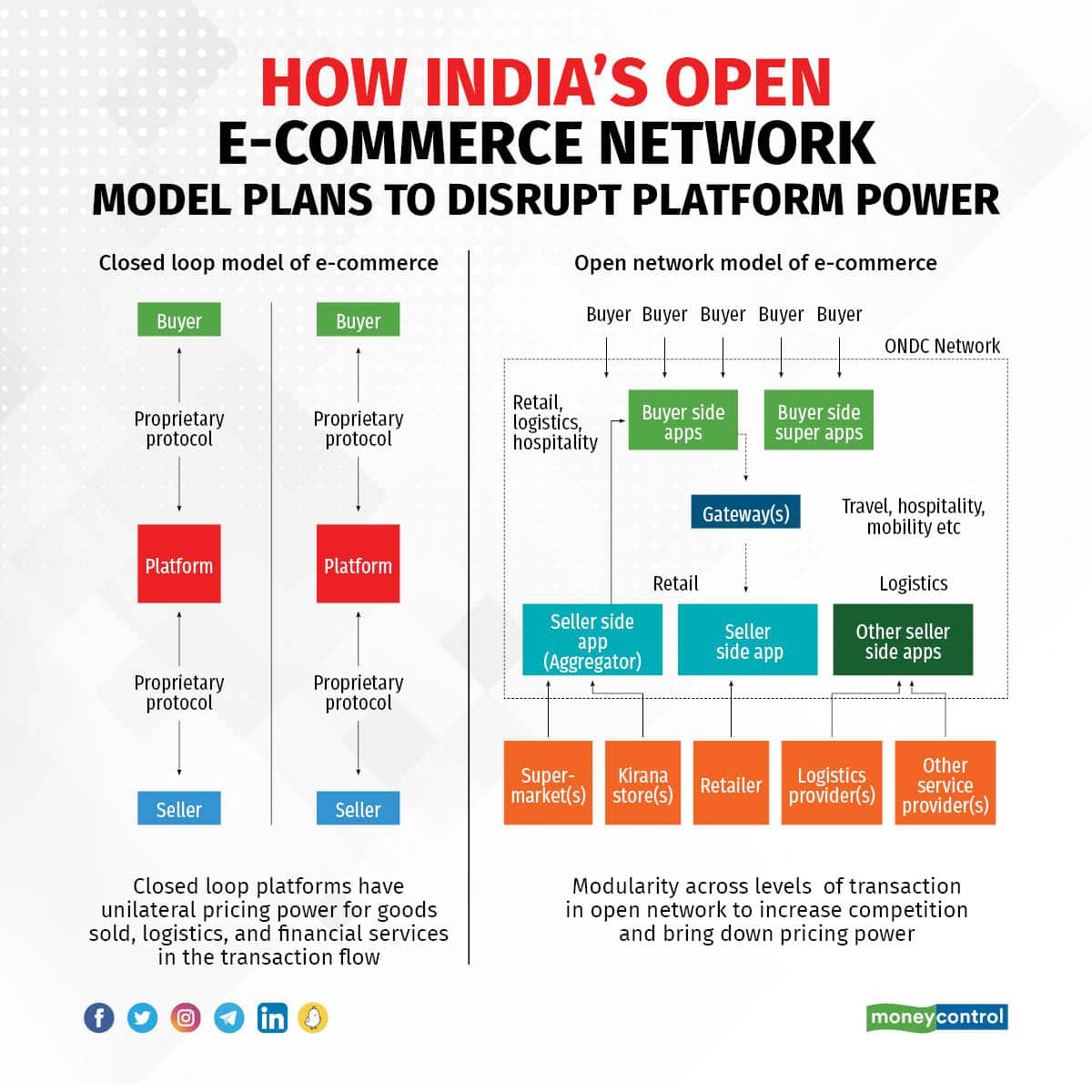

In the ‘closed-loop’ version of e-commerce that we are familiar with, one platform takes care of the entire value chain of one transaction. When you log into an app ‘A’ and search for mobile phones, the platform relies on your past purchase history, location and other data to personalise the results that you see.

Not only are those search results limited by which brands or sellers have tied up with the platform, but there is a good chance that it gives better visibility to some favoured sellers—either those that have paid for ads or the ones that may actually be owned by the platform itself.

Once you have decided what you want to buy from that limited selection of goods and paid for the transaction, the platform’s own logistics arm or a partner it has tied up with will deliver the products to your doorstep. And in case the platform’s logistics capabilities can’t deliver to that address, the transaction won’t go through.

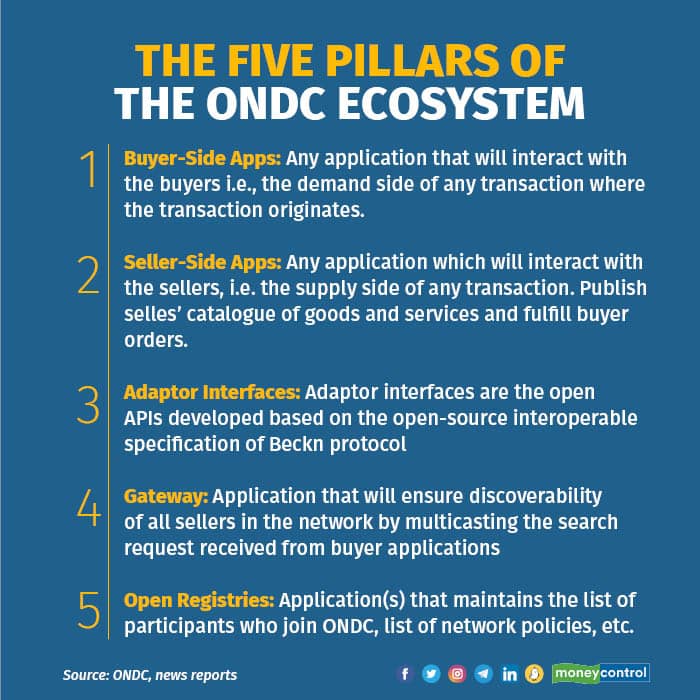

The ONDC model breaks down this value chain into multiple parts such as the buyer-side app, the gateway, the seller-side app and logistics providers.

Any app—be it an e-commerce platform, a banking app, a D2C app, a cab hailing app—can be a ‘buyer-side app’ where the consumer logs into, searches for things and completes a transaction.

Similarly, a seller-side app could be any platform that registers sellers of goods or services—fashion brands, wholesalers or retailers, restaurants, cab drivers, kirana stores and even home service providers like plumbers or electricians.

An e-commerce platform can choose to enlist itself as both buyer and seller app—or only one of those.

Now, when the consumer searches for a product on a buyer app, it will relay that information to a gateway which will send it to all the seller apps on the network. After the seller apps respond to the request from the gateway and show it all relevant results, the gateway relays the information back to the buyer app and the consumer gets to see a much wider catalogue of offerings.

(Of course, all these would only happen on apps or e-commerce platforms that integrate themselves with the network.)

Next comes the logistics part. For all those cases where the seller-side platform cannot deliver to a particular address, the buyer will get an option to choose from multiple logistics service providers who can fulfil the order. This will again happen through the gateway mechanism.

This open-loop model of e-commerce is expected to benefit sellers too. At present, any e-commerce seller has to register separately with every platform. On the open network, it would need to register only once with any of the sellers to be visible across apps and would also have a unified pool of reviews and ratings.

More importantly, the seller on-boarding process will be standardised across ONDC participants so that there is a single, accessible template for all sellers.

Behind the scenes

Although ONDC pilots started at the end of April this year, people close to the developments say that it will take another 6-12 months for all the pieces of the puzzle to come together.

At present, Paytm Mall has signed up with the network as a buyer app. Tech companies like Amazon, Flipkart, Google, Shopify and retail majors such as ITC, Dabur and Hindustan Unilever are reportedly in talks to join the network.

According to the commerce ministry officials, 80 firms are currently working with the network and are at different stages of integration. Further, ONDC reportedly plans to add 150 retailers in five cities during the pilot phase.

One of the most important components of the network will be the gateways as these will fetch results from various seller-side apps and show it to consumers. According to sources, ONDC is working on a framework for regular audits of the gateways so that they do not favour one seller over another. In the ongoing pilots, the gateway services are being provided by Protean e-Gov Technologies.

Moneycontrol reported earlier that ONDC may start charging consumers a per-transaction fee of 1-2 percent by the end of the year, and the number could go down to as low as 0.1 percent when it hits scale, according to sources aware of the matter.

The open e-commerce network is currently not charging any fees to customers.

While ONDC is piloting its protocols free of charge for both buyer-side and seller-side apps at present, eventually it plans to seek a subscription fee from the buyer and seller platforms that may amount to a few thousand rupees.

“The per-transaction fee could be 1.5 percent initially, and eventually may even be as low as 0.1 percent or 0.2 percent when the network

hits massive volumes. This comes out of the price paid. When an item is bought, the consumer pays for it,” said a person in the know.

T Koshy, CEO and MD of ONDC, said that the network will not prescribe any specific fees to be charged by participants like buyer-side apps,

seller-side apps and logistics providers.

“The open network model will lead to better prices due to increased competition. If anyone is charging unreasonable fees against the service they

offer, the buyers and sellers may shift to a different service provider,” he explained.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.