Saurabh Mukherjea, Rakshit Ranjan & Salil Desai

The year 2019 ended on a pretty strong wicket for equity markets around the world. Most major indices were up 10-25% during the year. The Dow Jones increased investors’ wealth by ~22%, the FTSE, Hang Seng, and India’s Nifty by ~12% and the Nikkei by 18%.

However, 2020 brought with it the rumblings of what eventually became a global pandemic, bringing some of the largest economies of the world to a standstill. As Covid19 spread worldwide, stock markets crashed globally, with many indices recording their worst-ever quarter performance and many others seeing the fastest-ever correction in recent history.

In India, the broader markets were anyway appearing shaky due to the weak growth in corporate profits for the past 6-7 years. Then came Covid-19 to add to investors’ troubles. And in the middle of all this came the collapse of Yes Bank. In a matter of weeks, the stock markets and the larger economy were dealing with a full-fledged crisis.

In five parts, Saurabh Mukherjea, founder of Marcellus Investment Managers, and his team elaborate on their investment process and emphasise on the techniques that have helped their fund navigate through tough markets and a crisis.

Read part 3 of the series here.

Part 2

Prudent Capital Allocation is Critical for Consistent Compounding

Summary: A characteristic feature of a Consistent Compounder is prudent capital allocation – that is, the choice of what to do with the free cash generated by the business year after year. The smartest management teams reinvest a bulk of the free cash in consolidating their dominance through

sustained business growth, without compromising on the returns from the incremental capital deployed.

If a firm is consistently generating large free cash flows, i.e. the excess of RoCE over the CoC, what should the management do with it? An obvious answer would be to reinvest the free cash into areas in which the firm already possesses deep-rooted competitive advantages (i.e. increasing the capital employed). This would keep the cycle of high RoCE leading to large free cash generation, in turn leading to higher capital employed and strong returns on that, going. However, as the firm grows and deepens its competitive advantages, the quantum of free cash flow available for redeployment tends to far exceed the amount that the business needs in order to keep growing.

For example, reinvesting to add manufacturing capacity far in excess of the growth potential of a product will end up depressing the RoCE as the capital employed rises without a commensurate increase in the earnings before interest and tax (EBIT). This then drives the management to explore one of the following two options.

- Diversification, usually inorganic: Pursuing growth outside their core business, either across geographies or product categories, is usually the most common use of free cash by managements. This can be achieved either organically, or inorganically, through acquisitions. Many firms prefer the inorganic route towards diversification, acquiring companies in related or unrelated businesses, forging joint ventures with other companies, acquiring minority stakes in other companies, etc.

- Returning the surplus cash back to shareholders through dividends or buybacks: When surplus cash cannot be effectively deployed without dragging down the RoCE sharply, it is prudent to return it to shareholders through special dividends or share buybacks.

Whilst all this sounds straightforward, many firms with a great core franchise that consistently generates high RoCE, have found it difficult to sensibly allocate surplus capital to diversify their business. Consider these examples highlighted below.

Creating shareholder value through M&A and offshore expansion has proved to be difficult for firms that have sustained high ROCEs in India.

Over the past 3-4 decades, middle-class household consumption in India has grown substantially across several essential products of day-to-day consumption. This has meant that over the past two decades, most dominant firms in these sectors have generated substantial amounts of surplus capital (i.e. capital after meeting the core capex requirements of the firm).

Between 1995 and 2005, there have been various examples of firms deploying their surplus capital towards M&A to acquire businesses in India. Many of these acquisitions have ended up generating substantial value for shareholders with RoCEs of the acquired businesses being well above their cost of capital. Some examples of these successful acquisitions include Hindustan Unilever’s acquisitions of TOMCO (Tata Oil Mills Company), Kwality, Brooke Bond, Kissan, Lakme, etc. during the 1990s; Dabur’s acquisition of Balsara (2005); Marico’s acquisition of Nihar (2006); and Pidilite’s acquisitions of Ranipal (1999), M-Seal (2000), Dr. Fixit (2000), Steelgrip (2002), Roff (2005), etc. These acquisitions have successfully added sustainable earnings growth drivers for these firms with already high RoCEs.

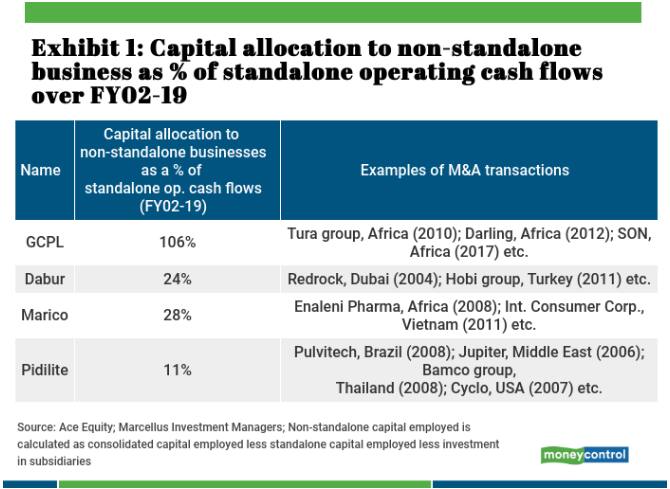

However, after 2005, several dominant Indian companies have deployed surplus capital towards international expansion/acquisitions – for example Godrej Consumer Products Ltd. (GCPL) in Africa, Indonesia, Latin America, Pidilite (Brazil, US, Middle East), Marico (Middle East, Bangladesh, South Africa), Dabur (Africa, US, Turkey, Egypt), Havells (Sylvania), Tata Steel (Europe), Asian Paints (Berger International, 2001), Bharti Airtel (Africa), etc.

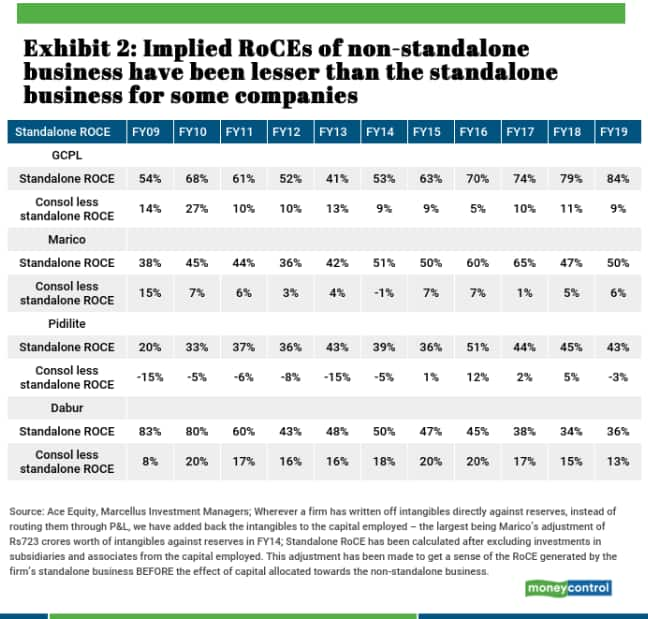

Analysing the RoCEs of some of the overseas acquisitions (RoCE of consolidated entity less RoCE of the standalone entity, where the India business is housed) shows how these international acquisitions have fared.

The following points are worth highlighting from this analysis:

- A substantial part (at times more than 100%) of operating cash flows generated from the standalone business has been deployed towards international acquisitions – see the second column of Exhibit 1

- Domestic (standalone) businesses of these firms have generated RoCEs substantially higher than the cost of capital, many at times even higher than 50% - see Exhibit 2. This is reflective of the strong moats built by these firms in India.

- International (non-standalone) business ROCEs of these firms have been sub-par, many at times substantially below the cost of capital – see Exhibit 2. This is reflective of the weak moats existing in these international businesses.

The analysis above highlights the fact that an inorganic growth strategy might not always be the right use of free cash. There might be many reasons for such a strategy to fail. Managing a business in an unknown (or lesser-known) overseas geography may require a different organisational structure than what the acquiring company operates within its home territory. Or, the acquisition might stretch management bandwidth and the lack of attention reflects in the business’ performance.

Whatever the reason for the poor RoCEs of the acquired business, it is clear that being a consistent compounder isn’t just about earnings high RoCEs, but also about the prudent use of the free cash generated as a result.

This brings us to another aspect of investment analysis in identifying Consistent Compounders that we have found useful – and that is on capital allocation. Whilst it is difficult to precisely forecast future capital allocation decisions of any firm, it helps to build conviction on the capital allocation approach of our different companies by analyzing their long term historical track-record of the same – how / why were certain capital allocation decisions taken in the past, what were the learnings subsequently and

how has the approach towards capital allocation evolved for the firm?

We have found that Consistent Compounders usually fall into two categories.

1. Type 1 – Capital redeployed only in core businesses historically: Firms such as Page Industries and Relaxo Footwears have reinvested on average, 50% and 90% respectively of their annual operating to expand manufacturing capacities in their core operations, enhance IT systems, etc. Moreover, every layer of geographical (within India) or product category expansion has been carried out organically in adjacencies which have a significant overlap with their existing core business. For instance, over two decades, Relaxo expanded pan-India into sports shoes and various sub-

segments of casual footwear, from being just a north-India player manufacturing flip-flops. Page started off by offering just men’s innerwear in the 1990s and has subsequently expanded into leisurewear, sportswear and outerwear categories for men, women and kids. For such companies,

we focus on building conviction on the runway of growth available to the firm’s core business, and the ability of the firm to maintain high RoCE on incremental capital deployment in existing core businesses.

2. Type 2 – Learnt from historical experiences around M&A: Firms like Asian Paints and Dr. Lal Pathlabs are open to doing acquisitions to grow their product portfolio or geographical presence, respectively. However, the promoter and management teams of these firms have demonstrated significant caution and restraint in considering such opportunities in the past. They have executed bolt-on acquisitions that do not risk a large part of the firm’s capital employed and have been cautious in deploying incremental capital into these acquired businesses. One exception though is a firm like Pidilite, which has had three distinct phases of large-sized M&A transactions in its history (as summarized below). The firm has acknowledged its mistakes, and implemented course-correction subsequently, which gives us conviction on capital allocation discipline likely to be pursued in the future.

Case Study: Pidilite’s capital allocation

It is worthwhile to look at Pidilite’s capital allocation track record in a little detail to drive home the point of how crucial prudent capital allocation is to long-term consistent compounding.

- Phase 1 (1999 to 2005) – Successful domestic M&A: After having spent five decades in establishing a monopoly in white glue (Fevicol), Pidilite started acquiring and building other adhesive and sealant brands to expand its product portfolio and to extend the firm’s channel presence and intermediary influence. The acquisitions included: a) Ranipal in 1999 for Rs 4 crores; b) M-Seal and Dr. Fixit in 2000 for Rs 32 crores; c) Steelgrip in 2002 for Rs 10 crores; and d) Roff in 2005 for an undisclosed amount. Capital deployed towards acquiring these firms was approx. 11% of the total operating cash flows generated by Pidilite over this period. Most of these acquisitions have become monopolies in their respective categories by now and have delivered RoOCEs substantially higher than the cost of capital for Pidilite. Thanks to this phase of expansion, Pidilite has one of the most diversified distribution networks, with its products reaching the customer through multiple channels, including convenience stores (kiranas), hardware stores, paint shops, modern retail outlets, e-commerce, paanwalas as well as stationery shops.

- Phase 2 (2006 to 2014) – Unsuccessful international M&A: Pidilite deployed close to ~Rs 685 crores in international acquisitions (26% of operating cash flows over this nine-year period) in Brazil, Middle East, USA and in acquiring an elastomer manufacturing plant in France. Pidilite bought small companies, some of which were operating in unrelated industries, without any market leadership. In countries like Brazil, the acquisitions were faced with economic collapse in the country, and issues with the legacy management team of the company. Over the past decade,

Pidilite has written off ~Rs 175 crores worth of its investments in subsidiaries in Brazil and the Middle East, and ~Rs 300 crores of its investments in the elastomer project. The acquisition made in the USA (Cyclo) has been sold off in 2017 for ~Rs 30 crores.

- Phase 3 (2014 to 2019) – Successful domestic acquisitions: Having learned from its mistakes made in the preceding phase of international acquisitions, Pidilite resumed its focus on frequently acquiring smaller domestic competitors in its core business. For example, Bluecoat has been acquired for ~Rs 260 crores (6% of FY14-19 operating cash flows) and Suparshva for an undisclosed consideration. These acquisitions have turned out to be substantially RoCE accretive for Pidilite. The firm has also deployed ~Rs 300 crores over FY14-19 (~7% of operating cash flows and ~2-3% of capital employed over this period) to acquire businesses in adjacent categories (CIPY – floor coatings; Nina and Percept – waterproofing contractors) and has formed JVs with MNCs like ICA for niche products like wood finishes. These businesses have shown significant improvement in financial performance post-acquisition. In addition to disciplined capital allocation towards M&A in this phase, Pidilite also announced (and completed) a share buyback of Rs 500 crores in FY18 at Rs 1,000 per share, a 12-13% premium to the prevailing market price. This share buyback amounted to 14% of capital employed and 63% of operating cash flows in FY18.

(This is the second installment of a five-part series by Saurabh Mukherjea, founder of Marcellus Investment Managers. Rakshit Ranjan is Portfolio Manager, and Salil Desai, Portfolio Counsellor at Marcellus Investment Managers.)Read the first installment here.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.