The year 2019 ended on a pretty strong wicket for equity markets around the world. Most major indices were up 10-25% during the year. The Dow Jones increased investors’ wealth by ~22%, the FTSE, Hang Seng, and India’s Nifty by ~12% and the Nikkei by 18%.

However, 2020 brought with it the rumblings of what eventually became a global pandemic, bringing some of the largest economies of the world to a standstill. As Covid19 spread worldwide, stock markets crashed globally, with many indices recording their worst-ever quarter performance and many others seeing the fastest-ever correction in recent history.

In India, the broader markets were anyway appearing shaky due to the weak growth in corporate profits for the past 6-7 years. Then came Covid-19 to add to investors’ troubles. And in the middle of all this came the collapse of Yes Bank. In a matter of weeks, the stock markets and the larger economy were dealing with a full-fledged crisis.

In five parts, Saurabh Mukherjea, founder of Marcellus Investment Managers, and his team elaborate on their investment process and emphasise on the techniques that have helped their fund navigate through tough markets and a crisis.

Part 3Crushing Risk is More Rewarding than Chasing ReturnsTraditional investing theories can be detrimental to portfolio returnsThe Efficient Markets Hypothesis (EMH), one of the more popular investing theories, contends that since stock prices efficiently discount all the available information in the market, it is impossible to beat the market. On the other hand, there is the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM), which says that it is possible to increase portfolio returns is to increase systemic risk – i.e. buying high beta stocks.

Whilst Warren Buffett’s rubbishing of the EMH is well-known (click here), the CAPM still remains popular, both in classrooms and in practice.The contention that returns are proportional to risk makes many investors invest in products without adequately appreciating the risks involved.

Investors need to minimise four types of risks if they want to generate steady and healthy investment returns in the Indian stockmarket:

• Accounting risk: Whilst we all now know how prominent public and private sector banks in India fudged their NPA figures for years on end until the RBI’s Asset Quality Review forced them to come clean, the same problem exists with several housing finance companies (who don’t come under the RBI’s purview). The accounts of a leading cement manufacturer don’t stack up. Neither does the annual report of high-flying retailer make sense. Ditto with a prominent petchem company and a prominent pharma company. In fact, many companies in the BSE500 have annual reports which do not pass scrutiny. Using a few accounting ratios and a financial model which contains time series data on 1300 of India’s largest listed companies, we seek to identify that 20% of the Indian stockmarket whose books can be readily relied upon.

• Top-line risk: At USD 2,000, India’s per capita income is still very low (less than half the level of Sri Lanka and a quarter of the level of South East Asian countries like Thailand and Malaysia). As a result, beyond the basic essentials of life – FMCG products, pharma products, basic apparel – most other products in India are luxury items for most Indians. As a result, even for small cars or entry-level two-wheelers, demand in India fluctuates wildly. Eg. Maruti Suzuki typically experiences 5-6 years of strong demand growth (growth well above 15% per annum) followed by 3-4 years of famine (growth well below 5% per annum). Whilst its cross-cycle average growth tends to be around 12%, the stock price volatility reflects the volatility of Maruti’s topline growth. In contrast, a company selling essential products like Asian Paints or Marico, tends to see steady revenue growth – between 10-20% per annum – pretty much every year. Investing in companies selling essential products in India therefore reduces risk.

• Bottom-line risk: As the cost of capital is still pretty high for India, it is rare to find Indian companies who spend heavily on genuine R&D. Understandably therefore, the Indian economy is characterized by rapid imitation – one company spots a niche (say, gold loan finance) and within a decade it has a 100 imitators. This rapid new entry squeezes the profitability of the first mover and thus creates risk for its shareholders. In order to reduce such risk we look for sectors where over extended periods of time, 1 or 2 companies cumulatively account for 80% of the sector’s profit pie. Such monopolies have lower volatility in their profit margin.

• Liquidity risk: India is the least liquid of the world’s top ten stock markets largely because promoters own more than half of the shares outstanding in the Indian market. As a result of this, beyond the top 30 or so stocks in India, liquidity – measured by average daily traded volume (ADV) – drops rapidly. By the time you are in the lower reaches of the BSE100, ADV is well below $5m per day. Such low liquidity creates stock price gyrations as investors go through their cycles of election induced euphoria followed by accounting fraud induced panic. Tilting the portfolio towards liquid stocks reduces this risk.

The advocates of the CAPM argue that investors who take any of the four risks outlined in the preceding section should be rewarded by the market for taking that extra risk. That line of thinking does not work in India.

In the book “Coffee Can Investing: the Low Risk Route to Stupendous Wealth” (Saurabh Mukherjea, Rakshit Ranjan and Pranab Uniyal; 2018), it’s been shown that identifying stocks with low accounting risk, low top-line risk and low bottom-line risk using a simple quantitative filter (revenue growth should be in double digits and ROCE should be above 15% every year for ten consecutive years) consistently generates returns in the vicinity of 20% per annum with share price volatility half that of the Nifty. Even without adjusting for risk (volatility), you are far better off investing in this portfolio rather than in the Nifty. In fact, you are far better off investing in this portfolio – akin to our Consistent Compounder Portfolio (CCP) – relative to almost every other asset class in India (including real estate, private equity and government bonds) – see chart above. You do NOT have to take extra risk in India (or load up on beta) to get healthy returns.

Why does this simple filter-based approach to creating a CCP work so consistently? Because the CCP basically seeks to minimise the four risks outlined in the preceding section. If a company is able to grow revenues at double digits every year for ten consecutive years, it is almost certainly selling an essential product which will be in demand in both economic booms and busts. Secondly, if a company is able to generate ROCE above 15% every year for ten consecutive years, it is highly likely to be a dominant/moated franchise. (The vast majority of the Nifty companies have not generated an ROCE of 15% even once in the past ten years.)

Therefore, it makes imminently more sense to crush risk rather than embracing unwarranted risk.

Crises expose corporate fraudsThe risks highlighted above assume critical importance during a crisis. The most spectacular accounting frauds usually come to light when the stock market is tanking and the access to capital starts drying up. For example, Satyam Computers imploded in January 2009, four months after the Lehman Bros bust triggered a liquidity freeze in India; the scandal in Enron came to light in October 2001, 15 months after the dotcom bust and a month after 9/11 had pushed the US stock market further into the mire; WorldCom filed for bankruptcy in July 2002 after having cooked its books frenetically in the wake of the dotcom bust; and Bernie Madoff confessed to his sons in December 2008 – three months after Lehhman went under – that his wealth management scheme was in reality a massive Ponzi scheme. As night follows day, when liquidity tightens, big accounting scams come to light.

This happens for three reasons. Firstly, the central driver of accounting fraud is the promoter’s need/desire to siphon cash out of the company. When liquidity is easily available, he can either cover his tracks by borrowing money in his own name and infusing it in the company (say, through short-term loans) or the company itself can avail of short-term loans. The surfeit of liquidity sloshing around the company creates an impression that everything is alright. However, when liquidity tightens, these short-term loans dry up and staff/suppliers/creditors raise the alarm that the company is out of cash. By this juncture, typically the Indian promoter has taken flight.

Secondly, the money that the promoter borrows is usually collateralised by either his properties or his shares. A liquidity crunch typically hits the value of both of these asset classes. That, in turn, leads lenders to issue margin calls to promoters. Thus, the promoter – who has already pilfered money from his listed entity – now finds himself being chased by his lenders. It wasn’t a coincidence we think that two prominent Indian jewellers took flight six months after wholesale money market rates started rising in India (from August 2017 onwards). Unless a miracle shores up the value of real estate and shares in India, we should expect more promoters to take flight rather than taking the trouble to meet margin calls.

Thirdly, in a growing economy, corporates can show genuine growth in revenues and hence justify the growing working capital needs. Hence in a booming economy everyone – shareholders, auditors, lenders – buys the logic of rising short term borrowing to finance working capital needs (even though the actual driver of higher borrowing might be the promoter’s pilferage of cash). When the economy then slows – in the wake of rising interest rates – that fig leaf is removed. The auditors, with their professional reputation on the line, now become less willing to sign off on growing pile of receivables. Given that from 2018 onwards, the Ministry of Corporate Affairs has oversight of the audit profession in India, we expect an increasing number of auditors to pull the plug on promoters who are cooking the books.

The importance of accounting quality“It has been far safer to steal large sums with a pen than small sums with a gun” – Warren Buffet

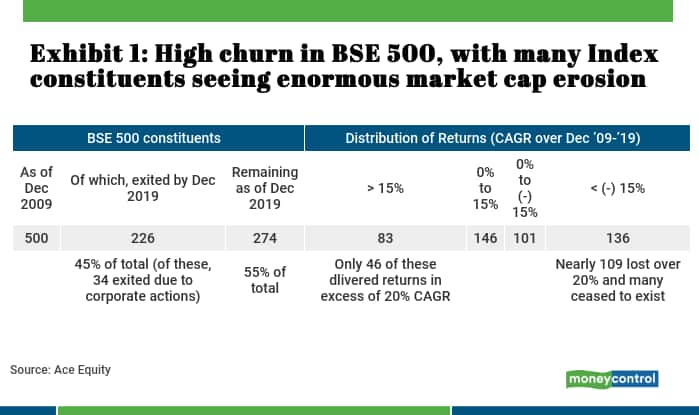

The annual churn in the BSE500 Index is as high as 12% p.a. – meaning 60 new companies become part of the Index every year, replacing 60 incumbents. This high churn ratio signifies that most existing incumbents are unable to sustain their place in the index and, over the course of time, make way for more deserving candidates. A closer analysis of the stocks exiting the BSE500 over the last 5 to 10 years indicate that most exits had little to do with business downturns but were mainly due to corporate governance/accounting lapses and capital misallocations at these firms.

If one were to look at BSE500 as it stood in December 2009, out of the total 500 member stocks then, only 274 stocks continue to remain in the index. In other words, nearly 45% of the stocks have exited the index over the last ten years. On their way out, most of these stocks saw significant erosion in their shareholders’ wealth (on an average, the companies which exited the index have lost 40% of their December 2009 market cap). Hence, for every Bajaj Finance and Eicher Motors which significantly enriched their investors, there has been an Educomp and Lanco Infratech which left their minority shareholders high and dry.

While the number of companies which have generated enormous wealth for their shareholders are bound to be a handful, the number of companies which have destroyed shareholders’ wealth would be much more. Hence, the ability to stay away from dubious names is equally if not more important than the ability to discover a great company.

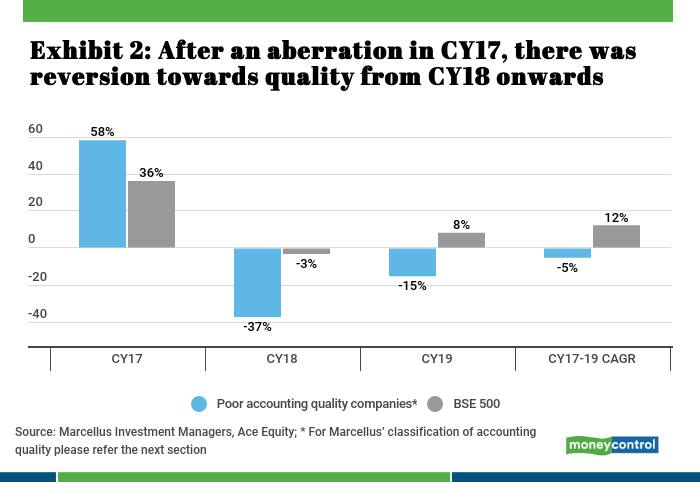

Quality may take a backseat momentarily but always makes a comebackIn the long run, high accounting quality and efficient capital allocation define investment success. A look at longer-term stock returns suggests a direct relationship between better accounting quality and superior stock performance. In the shorter run, however, markets do have a tendency to test investors’ patience even if the investor is using the most time tested and rational investment methods. Hence during this period of irrational exuberance and abundant liquidity, where there is pressure to chase near terms returns, quality does take a backseat. Take the instance of the bull market of CY17 which saw speculative excesses being created in lower-quality stocks.

However, things changed with the onset of CY18. As the cost of capital rose, liquidity started drying up and equity markets turned volatile. This, in turn, made investors more selective. Recurring news flow on auditor resignations further spooked investors through CY18. All of this, in turn, brought the focus back on accounting quality. This has resulted in good quality companies outperforming their poor-quality counterparts by a considerable margin in CY18 and continuing to do so in CY19.

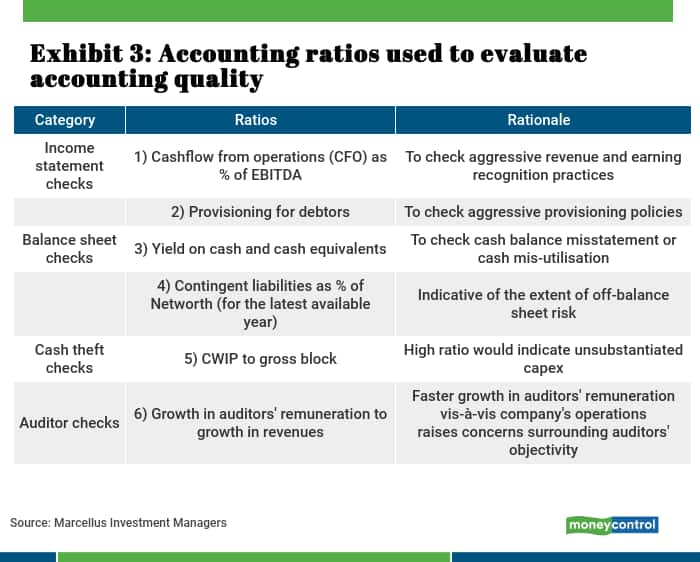

Evaluating the accounting quality of a company is a cornerstone of the investment at Marcellus. We have developed a set of 12 financial ratios that help us grade companies on their accounting quality. The selection of these ratios has been inspired by Howard M. Schilit’s legendary book on forensic accounting, “Financial Shenanigans’ (first published in 1993 and currently in its fourth edition). The book draws upon case studies of accounting frauds, including not just well-known cases such as Enron and WorldCom but also as numerous lesser-known instances of accounting trickery. The author then goes to draw lessons from these cases to create techniques for detecting misreporting and frauds in financial statements.

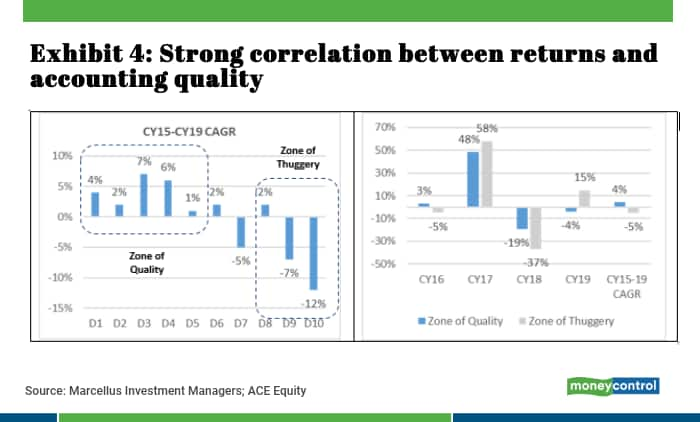

The 12 forensic accounting ratios we use cover checks around key financial statement categories like income statement (revenue/ earnings manipulation), balance sheet (correct representation of assets/liabilities), cash pilferage and audit quality checks. Some of these key ratios and rationale are shown in the below exhibit. We look at the historical consolidated financial statements for the universe of firms. We first rank stocks on each of the twelve ratios and give a final decile-based pecking order on accounting quality for stocks – with D1 being the best on accounting quality and D10 being the worst. The top 5 deciles i.e. D1 to D5 are generally indicative of a company with good accounting quality/practices – we call D1 to D5 the ‘Zone of Quality’ whereas the bottom 30% i.e. D8 to D10 generally represent companies with questionable accounting practices – we call this the ‘Zone of Thuggery’.

Over the longer term, there has been a strong correlation between the accounting quality as suggested by our forensic model and the shareholders returns. For instance, the ‘Zone of quality’ has outperformed the ‘Zone of thuggery’ by a whopping 9% p.a. over CY16-19.

There is another way to understand the effectiveness of this forensic model – there are around ~53 companies (out of the BSE 500) which constantly featured in D8 to D10 rankings in our accounting model for the years FY2015-18. Over CY16-19, these companies have on an average delivered negative CAGR of 13% compared to benchmark BSE 500’s 10% i.e. an underperformance of nearly 23% p.a.

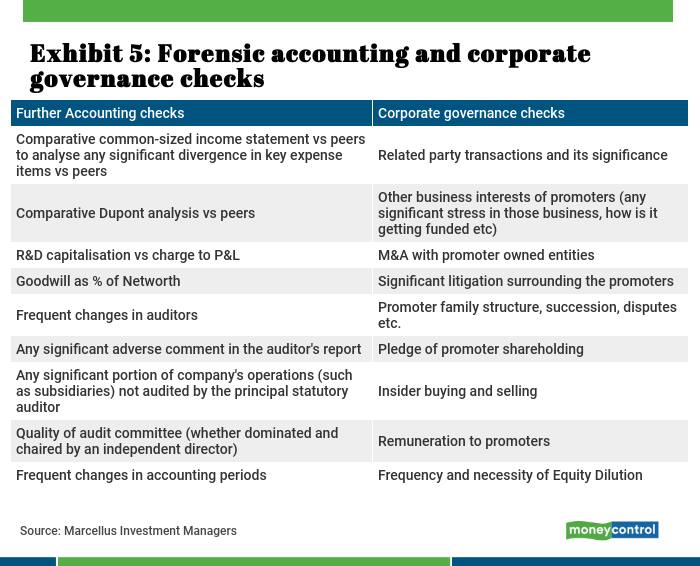

Beyond the forensic screensOur forensic framework helps us to weed out companies with dubious accounting quality. It also helps us identity the key accounting red flags for a company. However, our quest for accounting quality does not end there. There are several qualitative aspects of accounting and corporate governance which our forensic model may not be able to pick up due to lack of data uniformity across companies or where there are subjective judgements involved. Such areas can only be evaluated through a deep dive into historical financial statements and primary data checks around management integrity.

We have developed the following checklist for further accounting and corporate governance checks beyond the forensic model. This checklist forms an essential part of the qualitative assessment of stocks.

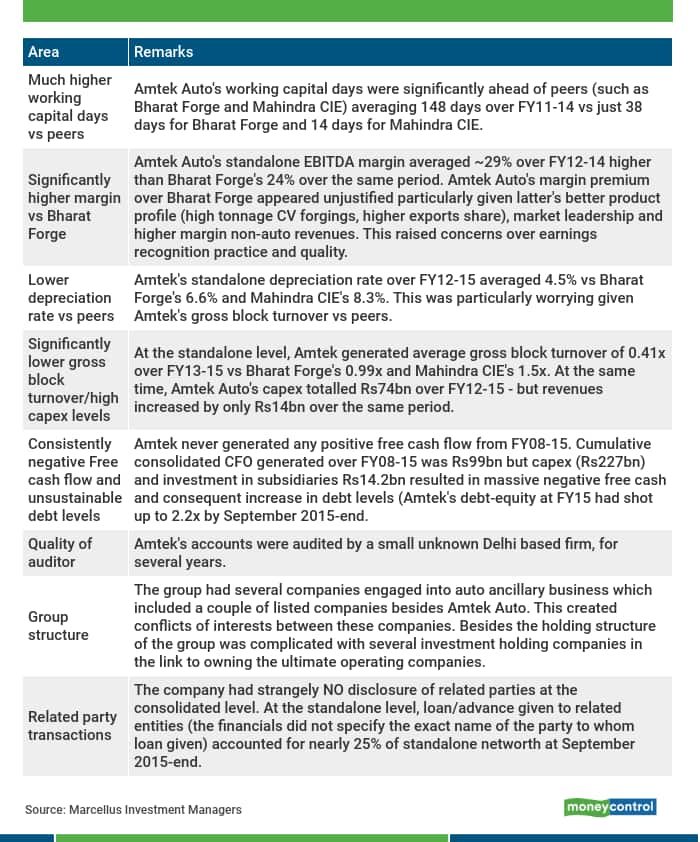

We produce below our first-hand experience of analysing Amtek Auto’s financial statements a few years ago. The stock looked extremely cheap on valuation multiples with very high margin profile but a very weak balance sheet. Our analysis pointed towards multiple glaring issues in its financials. We went on to be proved right on most of these things.

Read the first installment here.

Read the second installment here.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!