On a muggy day in early 2000s, I found Thamma (my paternal grandmother) struggling to comb and tie her thick and long black hair into a bun. A big ball had emerged on the back of her head. She couldn’t rest her head on the pillow either for the rest of her days. She told me she’d inserted a hairpin too hard in.

With Class X board exams close at hand, I was told: grandma will be fine. Reassurances are lies we tell ourselves. I saw my super active grandmother shrivel on a bed, break into sweat, writhing in pain, being irritable with the effect those nuclear medicines had on her. She couldn’t eat what she loved, couldn’t meet those she loved, the water with which she was wiped clean would turn a deep medicinal yellow. I was grappling with all these changes when I was told Big C had come visiting our home. She had Stage IV thyroid cancer, chances were dim. Just a few years ago, I lost a dear uncle to it but I wasn’t ready for this and tending to her left no room for the future grief yet. Thamma, the matriarch, was my first chef, storyteller, confidante, saviour and partner in crime, we were a bit like Tridib and his Thamma from Amitav Ghosh’s novel The Shadow Lines (1988). One day, Baba took her in his off-white Fiat Padmini for what was a regular check-up. She waved at me from the car’s rear window glass, I waved backed from the balcony. That would become my last memory of her. She was gone. There was no closure.

I wonder now if she could have just put an end to her miseries by walking to death instead of death pulling her, would she have gone with a smile? Like Chika Kapadia does in Nilesh Maniyar and Shonali Bose’s personal documentary A Fly on the Wall, which premiered at Busan International Film Festival (BIFF), came home to MAMI Mumbai Film Festival and next goes to Dharamshala International Film Festival (DIFF).

Grandparents will die, we are subconsciously prepared for it. But we are almost never prepared for when a friend dies, even if that be of his choosing. Watching a full-of-life, albeit terminally ill, Kapadia embrace death was to being reminded of Kahlil Gibran’s lines: “You would know the secret of death./ But how shall you find it unless you seek it in the heart of life? / The owl whose night-bound eyes are blind unto the day cannot unveil the mystery of light./ If you would indeed behold the spirit of death, open your heart wide unto the body of life./ For life and death are one, even as the river and the sea are one.”

Maniyar and Bose’s documentary, over an hour and a half, follows the last few days of her friend of 25 years Chika Kapadia, who was given four months to live and who breathed his last in Zürich in August 2022, with the help of physician-assisted suicide, provided by Dignitas. Switzerland is one of the only countries to provide this option to people.

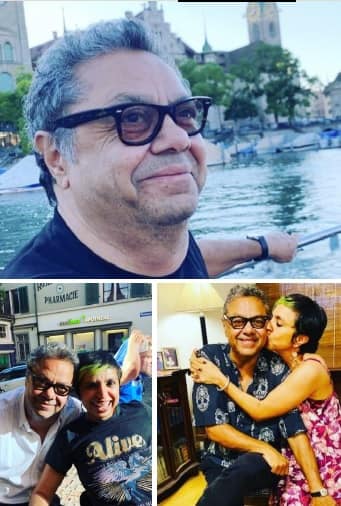

The late Chika Kapadia and Shonali Bose.

The late Chika Kapadia and Shonali Bose.The premise of the film reminds me of Pablo Picasso’s oil painting Science and Charity (1897), with a doctor, patient and a nurse with a child. Bose is that nurse, and her camera is that child, capturing the sight that would come to it later in life. Though Kapadia, with a huge lump on his throat, is anything but a morose, dying man on a bed. He tells death: bring it on.

A Fly on the Wall, a personal diary of the days leading up to his willing death, which addresses cinema’s final anathema: to shoot a person dying on camera, is high on emotion and less on the distant intellectual probe into the topic of euthanasia or physician assisted-suicide. A candid Bose, through her vulnerable moments and unfiltered emotions on camera, provokes us to think about filmmaking and human decency. But, also, about friendship/love and human rights: let you pal die or respect his right and be there for him. The shock value of the harrowing documentary is tamed by a vivacious man who asserts his ultimate right to choose the way he shall depart. Kapadia, the self-proclaimed “man who cannot die” has Stage IV Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma (ATC), a rare kind of cancer. He’s bought a one-way ticket to Zurich and has a dying wish: that his ‘going away party’ (his final days) be filmed by his filmmaker friend. Bose (with Maniyar) is on board, even if there’s a tug of war, internally, and minor skirmishes externally as Kapadia dictates shot designs and breakdowns of the film he’d like her to make and compels her to persuade his family to make the film. Bose refuses to start a conflict or be a fly on the wall.

Kapadia says his courage stems from his privilege: “Death is a part of life. You’ve got to stop running away from it. You’ve got to see it happen in a beautiful way. Out. Of. Choice.” Honesty, consent and a clarity of intent bolster this documentary, which is interspersed with postcards with his daily thoughts on death and afterlife. There is no discussion, arguments, debates about the ethics of the divisive issue of euthanasia in the film though, which champions the cause Dignitas stands for.

Death is a recurring theme in Bose’s films. She lost her teenager son Ishan in 2010, and since then, the subject of her cinema dwelled upon the subject of the ultimate reality. In her National Award-winning film Amu (2005), Kaju’s (Konkona Sen Sharma) mother, Keya (played by Bose’s aunt and CPI leader Brinda Karat) tells her about her birth parents’ death in the 1984 anti-Sikh riots. In Margarita with a Straw (2014), Laila’s (Kalki Koechlin) mother Shubhangini (Revathy) dies of colon cancer, in an Ozu-esque scene design, minimal sound of the apparatus, the camera cuts close, at the level of the face of the characters. The Sky Is Pink (2019) is about the death of a teenager named Aisha Chaudhary (Zaira Wasim) from pulmonary fibrosis, a genetic disorder. A Fly on the Wall, in which she also mentions her son Ishan, is entirely on death. This is the third feature film collaboration between Maniyar and Bose after The Sky Is Pink and Margarita with a Straw.

Directors Shonali Bose and Nilesh Maniyar.

Directors Shonali Bose and Nilesh Maniyar.I have, however, one axe to grind with Maniyar and Bose. The documentary, which is a montage of mise-en-scènes, in which the human element trumps the form, and Tuomas Kantelinen’s minimalistic music and sound by Resul Pookutty add to the film, it feels like a home video, deficiently shot, mostly handheld, wherein Bose is doing the maximum talking and explaining. While the film shakes and breaks you, for both the man who’ll die and a filmmaker who has to face the ordeal of filming that, it also augurs the question whether there could have been other possibilities of making this film? The documentary feels a little like a BTS movie: more than a film about a man dying on his own terms, it comes across as a film about making a film about a man dying on his own terms. Was this an afterthought, owing to the disagreements between Kapadia and Bose, on the making and not making of the film, that may have left the filmmakers with not enough footage and material to make a different kind of film?

Bose has said in a Variety interview that this film “was not a choice, it was a dying wish that we acted on. Chika, my friend of 25 years, approached Nilesh and me with a deeply personal mission: to capture how peaceful physician-assisted suicide could be, hoping to reduce the fear and alarm surrounding it. He was willing to make something as intimate as his death public because he believed it was crucial to start this conversation. In those turbulent two weeks leading up to his death in Zurich, I was just coping and following Nilesh’s lead where the film was concerned.” Fair enough.

In short scenes, showing his old photos, Bose tells us that her friend Chika Kapadia was an electrical engineer who did the lighting of the huge Queen Mary ship docked at Long Beach, California. He left all that, and the Bombay-born moved back to India, and became a standup comedian. Then, he fell in love with a deep-sea diver and moved to Bali. But for a film on the dying man, one barely hears Kapadia talk about anything else besides his death entirely. That, of course, will be what solely preoccupies a dying man, but that is exactly where the filmmakers, to use Kapadia’s words, could have earned their stripes. A film about death doesn’t have to be only a singular meditation on death.

Shonali Bose and Chika Kapadia.

Shonali Bose and Chika Kapadia.In the penultimate moment when Kapadia recites the Robert Frost poem Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening and asks the 12-minute haunting The Low Spark Of High-Heeled Boys song by the rock band Traffic to be played, Chika Kapadia’s personality shines through. The film left me wanting to meet this man, know more about him, laugh at his jokes, he who led a full, colourful life, fell in love many times, and looked death in the eye in an almost John Donne way to say: Death, be not proud, though some have called thee / Mighty and dreadful, for thou art not so;/ For those whom thou think’st thou dost overthrow / Die not, poor Death, nor yet canst thou kill me. While I wish Kapadia was more fleshed out in this forever story on him, that he was much more than this one thing about him: his death, Maniyar and Bose's documentary, pulsating with Kapadia's warm and fun energy, leaves you numb, but is urgent and should start the conversation on one’s right to die, on their own terms. It leaves you shaken and stirred. Even broken, with a half-smile.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.