The farmers’ meeting with the government on December 3, again ended without any conclusive outcomes with the next round to be held on Saturday. Farmers from Punjab and Haryana have been at protesting against the farm legislations enacted by New Delhi fearing that the government will do away with minimum support prices (MSP). They also contest the weakening of the Agriculture Produce Market Committee (APMC) under the Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act.

They worry that the law would lead to inadequate demand for their produce in local markets. These are the two key issues among several others which have driven the farmer agitation.

The central government has assured that the MSP system will continue several times, but farmers are demanding a written assurance.

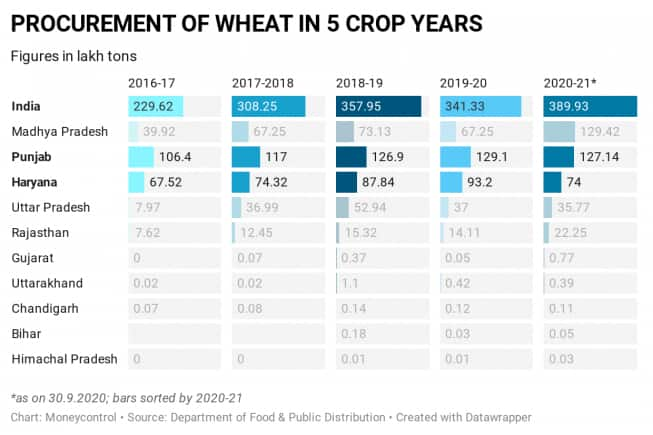

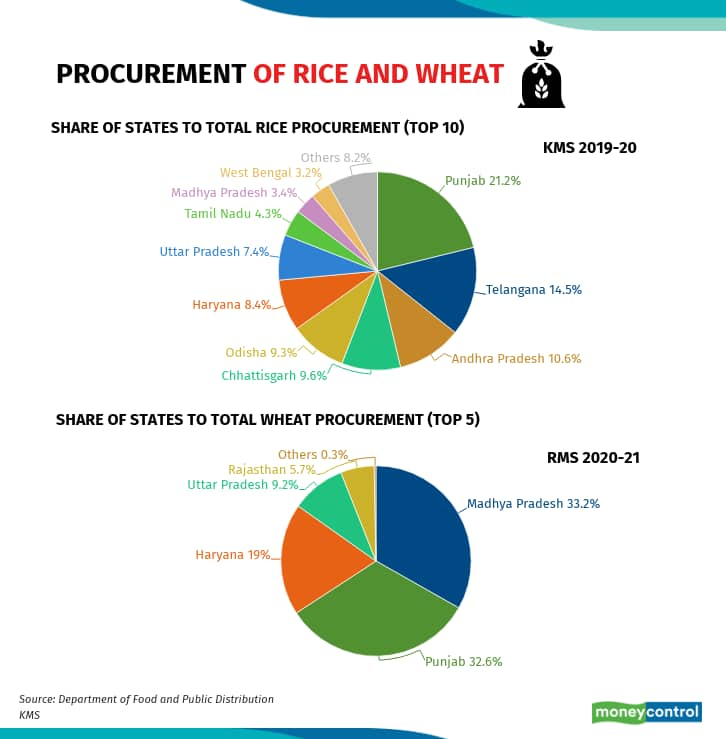

Punjab and Haryana hold high share in MSP procurementPunjab and Haryana farmers are the centre of the protests because these two states highly benefit from the MSP procurement system, especially for wheat and paddy crops, data show. Also, these are the two crops which are largely procured by the government compared to the other crops, and these two states are among the top producers.

Punjab is the second largest producer of wheat in the country and the third largest producer of rice. The state accounted for nearly 18 percent of India’s total wheat production and 11 percent of rice production in 2018-19. Haryana produced 12 percent of the country’s wheat output and 4 percent of rice.

Of the 513 lakh tonne of rice procurement recorded in India during 2019-20, Punjab’s share was 21 percent, the highest, and that of Haryana 8 percent, according to data from Department of Food and Public Distribution. For the rabi marketing season--2020-21 (as on September 30), Madhya Pradesh and Punjab show a higher share of wheat procurement at 33 percent each, followed by Haryana (19 percent). In the previous season too (2019-20), Punjab had the largest share (38 percent) of wheat procurement, followed by Haryana (27 percent).

Slicing the data another way, we see that the farmers in Punjab and Haryana sell a significant portion of their grain output under the government procurement system. In 2019-20, 92 percent of Punjab’s paddy output and 89 percent of Haryana’s was procured by the government. Similarly for wheat, government procurement accounted for almost 71 percent of Punjab’s production and 74 percent of Haryana’s ouput.

More than 12 million farmers’ availed MSP benefits for paddy during the 2019-20 kharif marketing season, of which 9 percent were from Punjab and 15 percent from Haryana. The rabi marketing season (2020-21) reported more than 4 million farmers availing the MSP for wheat. Almost one in four farmers were from Punjab and one in five from Haryana, according to the official data.

APMCs and procurement systemsThe other concern among farmers is making APMCs and procurement systems inconsequential. “Neither do the laws say anything about it [abolishing the MSP system and dismantling APMC mandis], nor is the MSP/APMC system going to disappear with these laws,” said Ashok Gulati, an agriculture expert and Infosys Chair professor for agriculture. “Yes, what would certainly come under pressure is the high commission of arhtiyas, mandi fees and cess that states collect, which account for as much as 8.5 percent over the MSP in Punjab, amounting to roughly Rs 4,500 to Rs 5,000 crore each year.”

Other experts too have opined that these protests are supported and encouraged by certain groups engaged in the farming sector who might lose out on their share with the new reforms coming into effect.

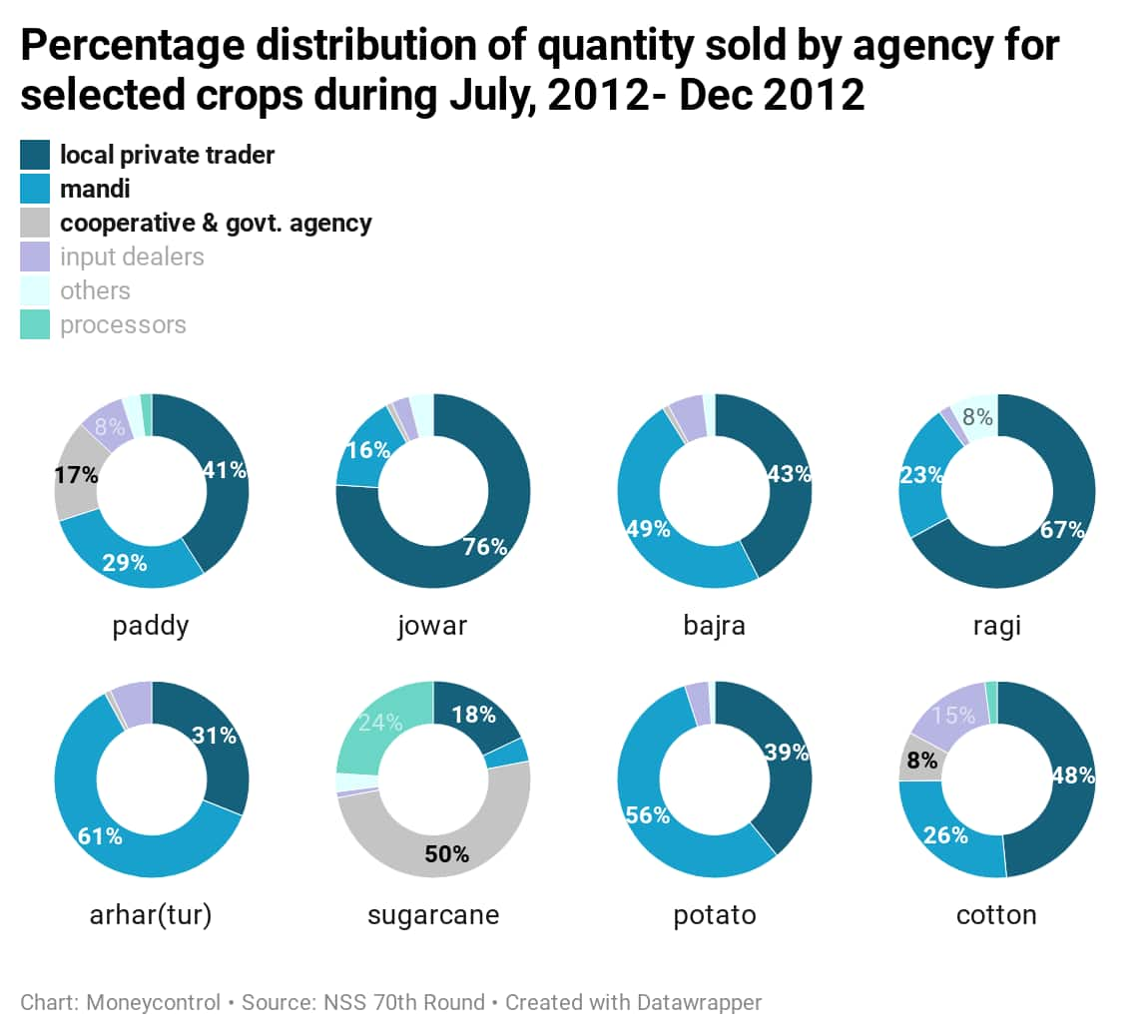

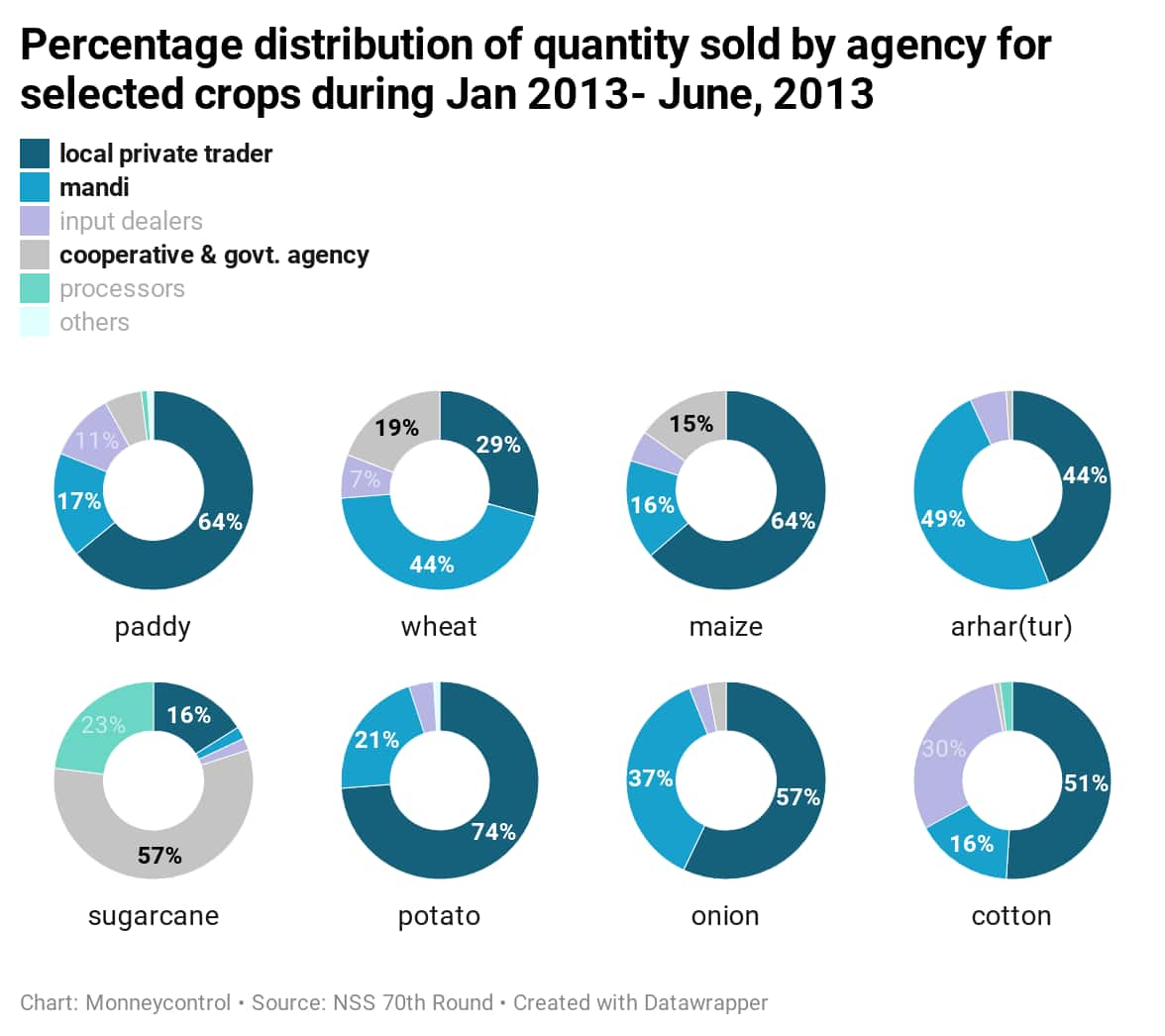

The NSS 70th round survey shows that the majority of farm output at the national level is sold to local private traders, followed by mandis. The chart below has details.

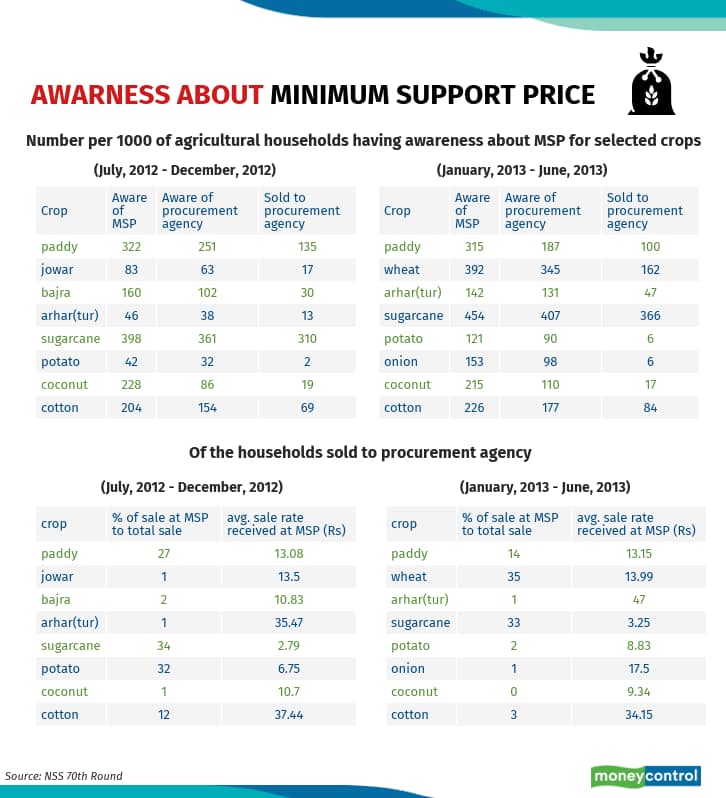

“The lower share of sale to cooperative and government agencies shows the lesser utilisation of procurement agencies which provide Minimum Support Price (MSP) to selected crops,” the report which came out in December 2014 said. The NSS survey findings also indicate that the majority of agriculture production in the country is for own consumption.

“Less than 10% of all crops are today sold at the MSP to government procurement agencies, so if the majority of farmers are selling to private traders even today, it is difficult to argue a catastrophe is around the corner if the MSP system goes; that is why the agitation is really limited to states like Punjab,” the Financial Express reported.

The survey also recorded data on households being aware of MSP but did not sell to the procurement agencies citing various reasons--such as non-availability of procurement agency or local purchaser and receiving better price over the MSP. The report findings indicate that among those aware of MSP majority of them did not sell it to procurement agencies, as can be seen from the data.

Does awareness of MSP have a role?Another report by the NITI Aayog released in 2016, on the evaluation of MSPs--based on a survey of a few states--noted that all households surveyed in Punjab sold their produce at MSP and none in the open market. On the contrary, the proportion of sale at MSP was lower in other states. All the farmers in Punjab were aware about MSP while the proportion of farmer awareness was lower among other states. Of 11 states, all farmers surveyed from four states--Andhra Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand were aware of MSP.

However, it also needs to be highlighted that when it comes to major crops like wheat and paddy, large farmers corner the benefits, the report said.

For instance, large farmers in Punjab consumed only 24 percent of their wheat produce and sold 47 percent at MSP. Small farmers consumed 53 percent of their produce and sold 27 percent at MSP, the report said.

Survey findings showed that farmers in three of the six sample states considered for wheat (Bihar, Gujarat and Uttarakhand), and three of the eight states for paddy (Gujarat, Karnataka and Maharashtra) did not sell at the MSP at all.

The caveat is that both surveys referred above are dated and there could be a possibility of change in demographics with regards to sale of produce over the years with increased awareness and technology.

“Pricing system has its limits in raising farmers’ incomes,” says Gulati. “More sustainable solutions lie in augmenting productivity, diversifying to high-value crops and shifting people out of agriculture to high productivity jobs elsewhere. But no one talked about these during these agitations,” he said.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.